Memoirs of Emma, lady Hamilton, the friend of Lord Nelson and the court of Naples; (33 page)

Read Memoirs of Emma, lady Hamilton, the friend of Lord Nelson and the court of Naples; Online

Authors: 1855-1933 Walter Sydney Sichel

Tags: #Hamilton, Emma, Lady, 1761?-1815, #Nelson, Horatio Nelson, Viscount, 1758-1805

approval. On June 21 he told Foote that the terms were settled, yet he then wrote to Acton that he did not know them. He kept the court in long ignorance of his manoeuvres. The strain of difficulty told on his nerves. Whatever his motives—and they were suspected—his action, though far less than Miche-roux's, was plainly equivocal, and while he mystified Foote, he failed to give any clear lead to the loyalists.

There is not much material to explain the tortuous negotiations of this period. The clue to them may perhaps be found in a desire to accord the patriots the same honourable terms as would be due to the French. If the rebels could secure these they would be more than satisfied, while Mejean trusted to time and the chance of the French squadron's arrival. Another motive was supplied by the hostages (including Micheroux's brother and cousin) and the refugees in the castles, among whom was Caracciolo, who, however, fled. Some amount of underhand collusion seems to have taken place now as afterwards. Foote was perplexed both by Ruffe's contradictory letters, and by Micheroux, whose authority he refused to recognise. On June 19, by invitation, Micheroux attended a conference at St. Elmo, with Mejean, Massa (commanding the Nuovo Castle), and Ruffo. A draft capitulation was signed with an armistice—afterwards extended to the French—which was to last till the arrival of the boats at Toulon, conveying such rebels as elected to go there, was notified. The whole affair was probably engineered by Micheroux in close touch with Mejean. Ruffo's compliance may be attributed to the necessities of his position and the importance of the Russian troops. He and Micheroux alternately laid the blame on each other's shoulders. By the 23rd the capitulation itself reached Foote, who was the last

to sign, and did so under a protest as to anything which might prejudice his king and country.

The document itself was most peculiar, considering the conditions of hostile and insurgent garrisons in the face of a successful conqueror. While it was conditional on Mejean's approval, it contained no mention of St. Elmo, and it was attended by a concurrent armistice, unspecified in it but very material to two of its main provisions. The truce's tenor may be gathered both from allusions in letters and from Nelson's emphatic memorandum, written before he had seen it, but read to and rejected by Ruffo. One must feel for the " patriots " in the mass, since they seem to. have been ultimately deceived, and many of them were noble. One must detest the vindictiveness with which the royal house pursued its triumph, though all that Jacobinism meant at .the time should be recalled. One must condemn the violence of the mob, for it was general and indiscriminate. But both the duplicity and the brutality were the outcome of the two despotisms which had so long been pitted against each other. Nor should it be forgotten that, as already noticed, Ferdinand himself had no objection to treat with the French, if only they would hand over St. Elmo to the loyalists. What he had strictly and constantly forbidden was any sort of capitulation for the rebels. And lastly it should be emphasised that, since on a previous occasion the rebels had broken a concluded truce, they might well repeat that perfidy. The city's horrors had been swelled by the reprisals of the Jacobins. They were now, in Hamilton's words, " reduced to a shabby condition," and it was this that led them to listen to the persuasions of Micheroux and the dictation of Mejean.

The terms of the armistice, according to Nelson's version of it, seem to have been as follows:—

It provided for a truce of twenty-one days, by the expiry of which the French and the patriot garrisons, if unrelieved, were to evacuate Naples. From Sac-chinelli's account of the preliminaries, their transport was to be free, i.e. at the King's expense. No wonder that Foote found the terms of capitulation " very favourable to the Republicans," though he based his consent on the express grounds that Ruffo was Viceroy, and that St. Elmo could not " with propriety be attacked " till advices were received that the Republicans had reached Toulon.

Nelson, however, took a much stronger view of this transaction. All armistices were reciprocal; if either party were " relieved " or succoured within a given time, a status quo must result. This armistice, however, provided, and on the most monstrous conditions, for the interruption of hostilities pending the mere chance of the enemy being relieved. If the French fleet had appeared instead of his, no one could suppose that the rebels would keep their word. If, on the other hand, the King's army were, as it was now being, " relieved " by the British squadron, the truce was ipso facto determined. The very presence of Nelson's ships, therefore, annulled this armistice.

So much for the truce. Now for the capitulation.

The troops composing the garrisons were to keep possession of the forts till the boats for their safe-conduct to Toulon were ready to sail. They were then to march out with all the honours of war. Should they prefer it, they were granted the option of remaining " unmolested " at Naples instead of proceeding by sea. These terms were to comprise all prisoners of war. All hostages were to be freed, but Micheroux's brother and cousin, the Bishop of Avellino, and the Archbishop of Salerno, were to remain in St. Elmo and in Me jean's hands, until the arrival of those sent

to Toulon should be ascertained. Every condition was subject to the French Mejean's approval. " They demand," wrote the raging Queen in her indignant comments, not " the approval of their sovereign, but the approval of a small number of Frenchmen. . . . What an absurdity to give hostages as though ^ve were the conquered! "

This luckless .treaty it was that intensified the morbid paroxysms of royal vengeance, for it converted the rebels of Naples into a foreign enemy. By insisting on amnesty as a right, by leaguing with the common foe, by rejecting more than one previous offer of clemency, by demanding their very utmost, they forfeited the least right to a grace which, however, it would have been far better in equity to have accorded. Ruffo, by owning himself unable to govern, by his helplessness to stem the riotous anarchy of vanquishers maddened by the suspicion of a second betrayal to the French, by his oblique manoeuvres, by his open breach of the royal trust, endangered not only himself but the countrymen whom he had so bravely led, and whom even now he desired to benefit.

Such was the state of affairs when Nelson, rounding the Posilippo point with his nineteen ships, sailed into the bay, drew up his fleet facing the harbour, and eyed the white flags flying from the castle towers. The Foiidroyant was hailed as an ark after the deluge. The quay was thronged with cheering loyalists. Ruffo, however, at his post by the bridge, must have been ill at ease. Nor could the Russians have been pleased, as they had reckoned on reaping the sole credit of a clever pacification. The poor patriots skulked and trembled in their fortresses. By night the whole city was all joy and illuminations, for Naples during the last few years had proved a kaleidoscope of massacre and merry-making. Not a minute was wasted by Nel-

son. He instantly signalled that the truce was ended. To Ruffo, through Hamilton, he communicated his fixed resolve " on no account to remain neutral." In accord with the Queen's advice, first to require a voluntary surrender, he further proposed to him that within two hours the French should be summoned to surrender, in which case they should receive a safe-conduct to France, but " as for the rebels and traitors, no power on earth" should " stand between their gracious King and them." He sent Ball and Trou-bridge with both these missives to the Cardinal, who flatly refused assent or concert. Next morning he sent them again, with no better result. He therefore himself notified to Mejean his curt summons to surrender, and to the rebels in the two castles that they must yield, and were forbidden " to embark or quit those places." The supple Cardinal, in his haste, had not only exceeded his commission, he had violated his express directions. Next evening Ruffo and Miche-roux (who was not admitted) visited the Foiidroyant to confer with Nelson. During the whole of this stormy interview the Hamiltons were present, Emma acting as interpretess. Nelson flatly repudiated all the subtleties of one called by Hamilton the pink of Italian finesse. He stood by the law that kings do not capitulate to rebels, and he dismissed Ruffo with his written opinion that the treaty needed to be ratified by his master. An Admiral, he added, was no match in such matters for a Cardinal.

All that day of June 25, letters, conferences, intrigues, confusion proceeded. From Palermo Acton wrote thrice. The foreign signatories entered a formal protest, probably arranged, and certainly carried by Micheroux to Nelson, who refused to recognise either it or him. Ruffo threatened to withdraw his riotous troops, and advised the rebels to profit by

his treaty and retire by land—a course fatal for them. By night a trumpeter had even announced that this move had the sanction of Mejean, who had told Micheroux that if war was resumed he would not be answerable for consequences. Massa, who asked for a conference, however, repulsed all Ruffo's overtures as coercion. The whole of Naples lay between two suspended fires; and yet Ruffo, afraid of St. Elmo, now besought Nelson to land the troops, the offer of which he had put off that very morning. By the next evening the two castles had unconditionally surrendered. The royal colours streamed from their turrets. The loyalist nobles of the " Eletti " had started to implore the King's presence, and Ruffo, leagued with the feudal barons, must have trembled. Feux de joie blazed in all the streets, and from every window, side by side, waved the British and Neapolitan flags.

In the meantime neither had Emma's energy been dormant; she did more than copy, and interpret, and translate the patois. She was a woman of action. Her enthusiasm spread among the common people, who adored her. She conjured with the Queen's name:— "• I had privily seen all the Loyal party, and having the head of the Lazzaronys an old friend, he came in the night of our arrival, and told me he had 90 thousand Lazeronis [-sic] ready, at the holding up of his finger, but only twenty with arms. Lord Nelson, to whom I enterpreted, got a large supply of arms for the rest, and they were deposited with this man. In the mean time the Calabreas [sic] were comiting murders-; the bombs we sent . . . were returned, and the city in confusion. I sent for this Pali, the head of the Lazeroni, and told him, in great confidence, that the King wou'd be soon at Naples, and that all that we required of him was to keep the city quiet for ten days from that moment. We gave him only one hundred of our marine

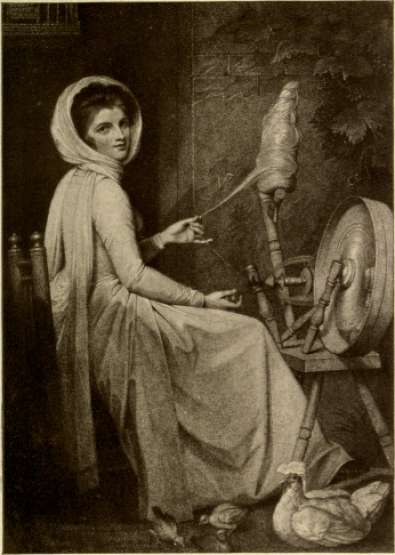

Lady Hamilton at the spinning wheel. From the original painting by George Romney.

troops. He with these brave men kept all the town in order . . . and he is to have promotion. I have thro' him made ' the Queen's party/ and the people have prayed for her to come back, and she is now very popular. I send her every night a messenger to Palermo, with all the news and letters, and she gives me the orders the same [way]. I have given audiences to those of her party, and settled matters between the nobility and Her Majesty. She is not to see on her arrival any of her former evil counsellors, nor the women of fashion, alltho' Ladys of the Bedchamber, formerly her friends and companions, who did her dishonour by their desolute life. All., all is changed. She has been very unfortunate; but she is a good woman, and has sense enough to profit by her past unhappiness, and will make for the future amende honorable for the past. In short, if I can judge, it may turn out fortunate that the Neapolitans have had a dose of Republicanism. . . . PS. —It wou'd be a charity to send me some things; for in saving all for my dear and royal friend, I lost my little all. Never mind."

Bravo! Emma, rash organiser and populariser of the Queen's party, bold equipper and encourager of Pali the Lazzaroni, who, when the King at last came to his own again, brought all his ninety thousand men to welcome him at sea. We shall hearken to Emma again ere long. For the present, the recital of sterner events must be resumed.

The plot, then, to place Naples at the mercy of the French had been foiled. The question that was to convulse the city on the following day was, On what terms had the castles surrendered!'

In trying to disentangle the difficulties of the next few days, a distinction should be borne in mind between the armistice made by the Cardinal with the rebels (and afterwards with the French), and the

Memoirs — Vol. 14—10

capitulation itself, which it was designed to further. It would almost seem as if some of the rebels had already contrived to escape from the convent of St. Martino, though not under the capitulatory clauses. Nelson would be most unlikely to reconsider any of these clauses, which he had peremptorily cancelled. But it might be thought possible that he would respect the armistice, which he had equally annulled. He might forbear to attack the rebel castles and even St. Elmo, with a view to their surrender. In exacting the unconditional surrender of the rebels, of which he had already given notice, and which he was again to notify, he never wavered. But it will be found that for the sake of the town's quietude, and pending some authoritative announcement of the King's pleasure (possibly recalling Ruffo), he did now temporarily desist from a siege, and so far obliged Ruffo. Mr. Gutteridge has shown by comparing and contrasting the documents, that when Nelson suddenly informed the Cardinal on June 26 that he would respect the armistice, he had no thought of respecting the capitulation, and that in the sequel he did not go back on his promise. It seems likely that the two cases of armistice and capitulation were so involved together by Micheroux and Ruffo as to persuade the patriots that they were free to escape under the terms of their convention, without submitting themselves to the sovereign whom they had defied, or abjuring the national foe.