Mendel's Dwarf (34 page)

Once the right length of DNA has been amplified (60 cycles of PCR using nested primers to guarantee purity), it is the simplest

matter in the world to perform a restriction digest

2

and find out whether there is that rogue misspelling, that

fuck

for

luck

, that AGG for GGG deep in the heart of the

FGFR3

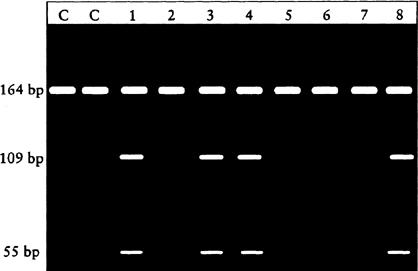

gene. The enzyme digests … or doesn’t digest; and then the sample of digested—or undigested—DNA is loaded onto a gel and a gentle electric potential eases the fragments along, jostling and straining. Digested fragments travel farther, because smaller, than undigested pieces. The DNA is stained with ethidium bromide so that the fragments may be viewed directly under ultraviolet light to find out how far they have gone, and whether there are the telltale digested fragments that mean:

MUTATION

and therefore:

DWARF

or not. A 164-base-pair fragment means normal. Jean would have given that to all the eggs. If the sample for a particular embryo contains only fragments of that size, then her 164-bp contribution has been matched by an identical one of mine, and the embryo is unaffected. If, beside her 164-bp fragment, the lane also shows a 109- and a 55-bp fragment, then that embryo has received the mutation from me.

It was evening when I finally pulled on a rubber glove and picked the slab of gel out of its mold. It shivered in my hand like something on the edge of life, a cloudy gray submarine growth, a jellyfish. I retreated to the dark room. It took no more than a few moments to put on a protective mask, to clamber onto a stool, to lay the gel on the viewer, to snap on the UV light, and bring the slab of jelly to life. Deep inside glowed bands of ghostly mauve.

“What’s that?” Eric asked, barging in for something or other.

“Oh, nothing special.”

He put on goggles and peered over my shoulder. “Isn’t that one of ours?”

“Just checking something.”

He barged out again. The slab of jelly looked like any other of the hundreds of gels we had run. It

could

have been any one of them; but it was mine.

Besides the controls there were eight lanes. Eight lanes, eight embryos:

You don’t have to be an expert to read it, do you? It was one of Uncle Gregor’s ratios. Embryos 2, 5, 6, and 7 were unaffected; 1, 3, 4, and 8 were carrying the mutation. Fifty-fifty. One to one. One half. Chance, pure chance out of such a small sample as eight, had conspired to make it exact. Four of those fragile clusters of jelly, four of those proto-Benedicts or proto-Jeans, had received the extra restriction site from their erstwhile father. They were carrying the achondroplasia gene and would become, without a shadow of doubt, like me. The other four were clear. And I could decide.

The Rotwang family went to Vienna, as so many families had done in the past and would do in the coming years, fleeing political

unrest. For the moment Vienna was far enough, but within seventy years you would have to travel to another continent altogether to be quite safe, and the people you would be fleeing from were those who had turned genetics into a creed.

That torrid summer, Mendel forgot Frau Rotwang. Memory is a labile thing. Whatever he had thought of her, he forgot her. At least he expunged her from the surface of his memory, from that part that wrestled with the intricate dance of genes. That torrid summer an attack of the pea weevil,

Bruchus pisi

, decimated his crop and he was constrained to abandon the plants that had been his children for almost a decade. He sniffed and shrugged and turned to the other species. Stubborn, bespectacled, introverted, he wandered among the beans and the four-o’clock, the campanula and the snapdragons, his scissors snipping away at anthers, his camel-hair brush slipping, penis-like, between the petals and dusting pollen from one flower to another. He collected the seeds, labeled them, and stored them; and the next season planted them out once more and waited. Yet again seeds swelled and sprouted, lines and lines of them—radicles nosing down into the soil, plumules ascending into the air, cotyledons opening to the sun like a pair of grasping hands. Rows and rows of fragile seedlings watched over by the friar, counted, reckoned, balanced—stock, maize, four-o’clock …

His ideas held, more or less (although he complained often enough to anyone who would listen about the difficulty of finding suitable plants, and the lack of time, and the lack of notice that anyone took): if you take two different varieties and cross them artificially, the offspring resemble one of the parents. (It was not always so: in four-o’clock,

Mirabilis jalapa

, for example, the hybrids were often intermediate between the two parents for flower color; but that didn’t upset him. Dominance was not always complete.) Then, if you self-pollinate the hybrids, the next generation gives you a ratio of three-to-one for any particular character pair; or, if the dominance was not complete as in

Mirabilis

, one-to-two-to-one. He had seen the same thing happen in mice. It meant that his simple mathematical model held true: inheritance was governed by particles, one contributed by each parent, no mingling of blood. There was nothing mysterious about it, nothing vague or mystical, no nameless fluids or influences, no hand of God. Just the plain facts of probability, a handing out of beads to children, like a gift from each parent, one bead from each parent for each inherited character.

Of course there were complications—pod color in

Phaseolus

(bean), for example. In this case he crossed dwarf bean, which has white flowers, with scarlet runner, which has scarlet flowers. The almost infertile hybrids had a variety of flower colors, ranging from scarlet to pale violet, and white flowers appeared only rarely (one in every thirty-one). Nevertheless, other characters (height, for example) obeyed the same rules as in his original peas, and even the flower color could probably be explained if, instead of the color arising from just one inherited factor, it was actually the result of two or more factors working additively.

3

This would also explain the range of different colors obtained. Moreover, in the case of stocks (

Matthiola

) he obtained precisely similar results to the pea …

But who would listen?

He even set up fertilizations under the microscope, using single pollen grains, in order to demonstrate that his assumption of one pollen grain to one ovule was true.

4

But who cared?

He demonstrated more of his hybrids to the Society for Natural Science, but species hybrids this time, things the members could understand, mules of the plant world, mongrels, bastards, mulattoes, half-castes, complex mixtures showing a blending of

various characters that the audience could relate to, but that were essentially uncountable and therefore of no real scientific interest. They did not want the mathematics of chance and probability or a deduction about the existence of inheritable, discrete factors. They did not, assuredly they did not, want to stare the future in the eye. “Science is physics; or it is stamp collecting,” Ernest Rutherford said. Stamp collecting was what interested the Brünn Society for Natural Science. They wanted to see bizarre crosses and strange monsters, neither one thing nor the other, neither fish nor fowl. It was the educated class’s version of going to the freak shows in the Klosterplatz. It almost came as a surprise when von Niessl (doubt that

von

) asked him to prepare his lecture on the pea in the form of a paper for inclusion in the Proceedings of the Society for the year 1865.

For publication Mendel went back to his original data. He tells us that in one of his letters. He went back to the original data and worked long hours going over the counts and tallies, checking them through, recalculating ratios, finding nothing out of place; then even longer hours copying it in his meticulous copperplate hand.

That torrid summer, like the thunderstorms that built up in the afternoon sky, the political crisis broke. Who now recalls the Schleswig-Holstein question, or remembers that there was a Seven Weeks’ War between Prussia and Austria? But that torrid summer, following the triumph or disaster (it depends on your point of view) at the battle of Königgrätz, the Austrian army was routed and Brünn was occupied by Prussian troops. They came as a surprise, a storm out of a calm summer day, preceded by nothing more than a vague sense of unease and a few fantastic rumors. At one moment there was the ordinary life of the city, and then, suddenly, Prussian soldiers were parading in the

Grosse Platz with their

pickelhauben

and their new breech-loading rifles. Their band played in the Augarten. They performed elaborate maneuvers in the parks beside the Schramm-Ring and the Kaiser-Ring. The King of Prussia visited the city just as Napoleon had before the battle of Austerlitz (who could have doubted that everyone saw the parallel); and a troop of cavalry was billeted on the monastery.

The invaders brought with them famine and cholera. The hospital just up the hill from the monastery filled to overflowing. The bells of the Augustinian church tolled almost continually for the dead (until the authorities forbade the practice because it was damaging to the citizens’ morale). And all that torrid, pestilential summer, Mendel wrote and revised and rewrote.

The paper on hybridization in the garden pea was published in the

Proceedings of the Brünn Society for the Study of Natural Science

. It was sent to 120 other societies and organizations around Europe. Copies went to the Universities of Vienna and Berlin, to the Royal Society and the Linnaean Society of London, to the Royal Horticultural Society at Kew, to Uppsala and Paris and Rome and St. Petersburg. No one read it. This was one of the three most significant and famous papers in the whole history of biology,

5

and no one took any notice. He also had forty offprints made of the paper, but we know of the fate of only five of them. To whom the others were sent, we just don’t know. One imagines Darwin, one imagines Haeckel, one imagines Huxley, one imagines Purkyn?. But we don’t know.