Mergers and Acquisitions For Dummies (86 page)

Read Mergers and Acquisitions For Dummies Online

Authors: Bill Snow

Customers and vendors

Customers and vendors

Buyer consents and approvals

Buyer consents and approvals

Part V

Closing the Deal . . . and Beyond!

In this part . . .

I

n this part, I dig into what happens after all the work is complete and it's time for closing. I discuss what occurs on that day and how to prevent last-minute issues that can blow up a deal. Lastly, I discuss some post-closing challenges that companies face as they integrate and combine.

Chapter 16

Knowing What to Expect on Closing Day

In This Chapter

Rounding up the closing's participants

Rounding up the closing's participants

Executing the actual closing

Executing the actual closing

Considering working capital adjustments

Considering working capital adjustments

A

fter the due diligence is completed and the purchase agreement finalized, closing time is nigh. Closing the deal occurs on a day called, ingeniously enough, closing day, where both parties sign the agreements and the money changes hands.

Although this setup seems simple and pretty straightforward, failure to be prepared can cause unexpected problems. When you've gotten this far, the last thing you want is to have the deal fall apart at the last minute because of a lack of planning.

In this chapter I introduce you to a day in the life of a closing: what happens, what to expect, and how to successfully close a deal.

Gathering the Necessary Parties

In the olden days (you know, before the advent of the Internet), closing day meant lots of people gathering in an office, signing a boatload of documents, perhaps haggling over last-minute details, and exchanging the money.

Today, most if not all closings are virtual, meaning they occur by fax and e-mail. Each party gathers in its respective lawyer's offices, signs what it needs to sign, and faxes/e-mails the signature pages (not the full documents) to the other side. The lawyers assemble the documents, confirm everything is in order, and make the instructions to wire the money.

Then it's done. The deal is closed.

Representatives from Buyer and Seller (that is, the owners and executives of both companies) are present at a closing, along with lawyers for both sides. Accountants, investment bankers, financing sources may also be present â they should at least be available by phone in case anything goes wrong.

Being prepared before closing is imperative; being unprepared increases the odds of tempers flaring, problems arising, and delays occurring. You don't want hiccups. The longer the closing takes, the greater the odds something goes wrong and the closing falls through. To increase the odds of a successful closing, the deal-makers (investment bankers) and lawyers should have all the business and legal aspects of the deal worked out. The lawyers should be prepared by having all the necessary documents laid out and ready to be signed.

Being prepared before closing is imperative; being unprepared increases the odds of tempers flaring, problems arising, and delays occurring. You don't want hiccups. The longer the closing takes, the greater the odds something goes wrong and the closing falls through. To increase the odds of a successful closing, the deal-makers (investment bankers) and lawyers should have all the business and legal aspects of the deal worked out. The lawyers should be prepared by having all the necessary documents laid out and ready to be signed.

Believe it or not, closing an M&A transaction is actually highly anticlimactic. No bells and whistles, no soaring music, no quick cut to a celebration in a tony watering hole. When the deal is done and the money has exchanged hands electronically, you simply go back to work or head home. It's just another day.

Walking Through the Closing Process

A closing should occur like a well-oiled machine, with steps that are well laid out and planned in advance. As a general rule, a closing should take less than two hours. Essentially, a closing should involve the considerations in the following sections, although variations to the following may exist.

Reviewing the flow of funds statement

The

flow of funds

is a very detailed list of the sources and uses of money â where the money comes from and where it goes. It's typically created in the days right before the closing and is among the last steps of the process. Usually Buyer is responsible for compiling this document (usually a spreadsheet). The statement lists everyone and every entity that is either providing money for the acquisition or getting money as a result of the closed deal, the amount of money being contributed or collected, all necessary contact information (company name, contact name, maybe a phone number), and wire instructions (bank, account number, and routing number).

Typical entities that show up on the flow of funds include the Buyer's and Seller's advisors (investment bankers, accountants, lawyers, and any other consultants), any bank or entity holding a debt that's being paid off at closing, and any vendors Seller has been slow to pay who are owed money. After all entities have received their cut, whatever is left over flows to Seller. After Buyer has compiled the flow of funds, he circulates it to Seller and any other advisors who may need to review the document for accuracy. Seller (and her advisors) should carefully check and double-check the document for accuracy and immediately contact Buyer with any corrections.

Advisors should be included in the flow of funds statement. Advisors who wait until after the deal closes to submit a bill will find their chances of being paid greatly diminished.

Advisors should be included in the flow of funds statement. Advisors who wait until after the deal closes to submit a bill will find their chances of being paid greatly diminished.

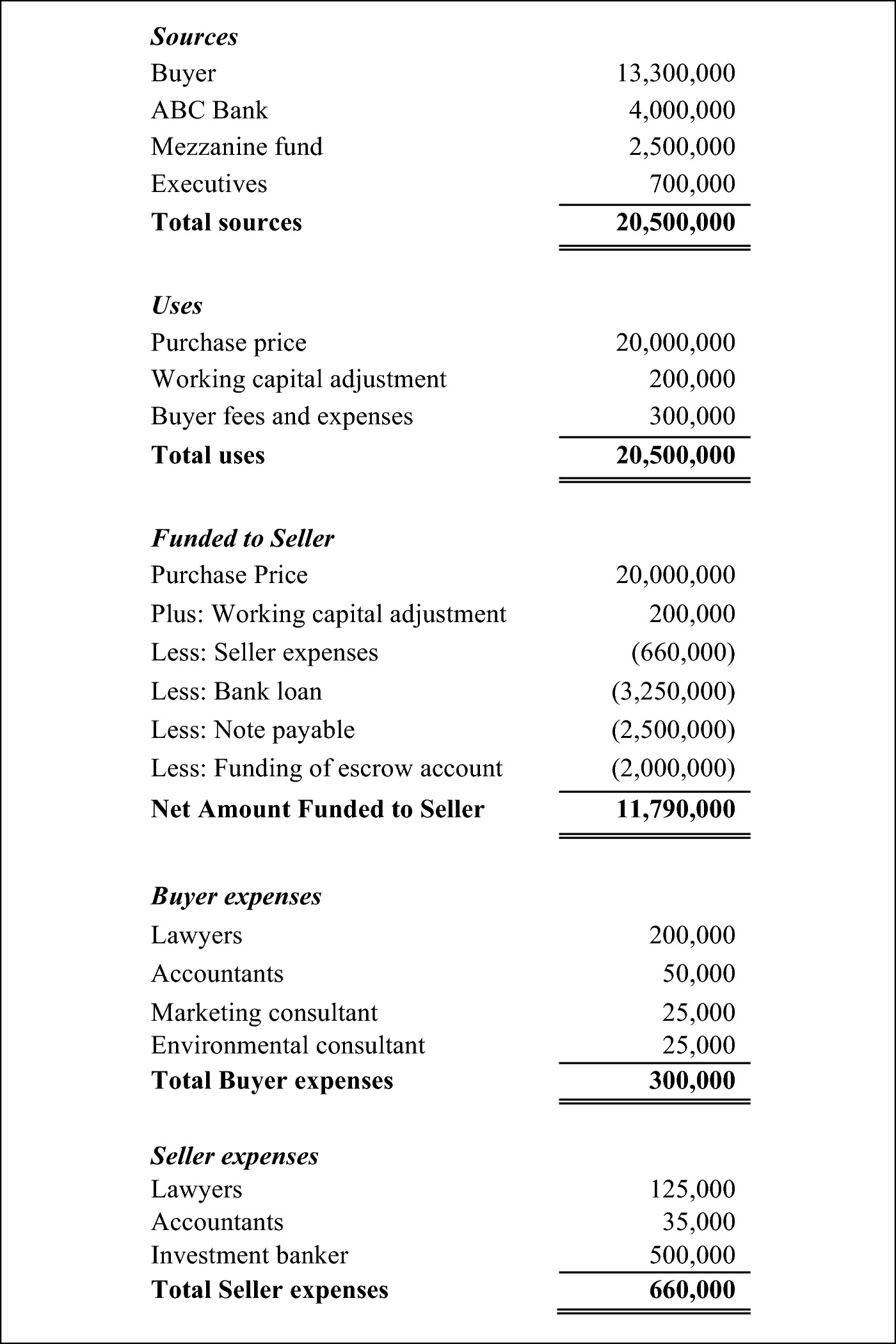

Take a look at the flow of funds statement in Figure 16-1. Buyer is contributing $13.3 million and obtaining $4 million from a bank, plus another $2.5 million from a mezzanine fund. The mezzanine fund is also known as

subordinated debt,

meaning it's subordinate (or second in line) behind the bank loan (also called

senior debt

). In addition, some executives from Buyer are contributing an aggregate amount of $700,000.

The purchase price of the business is $20 million. However, based on the purchase agreement, a working capital adjustment of $200,000 in Seller's favor needs to be added to the price. (See “Making a working capital adjustment” later in the chapter for more info on this adjustment.) Buyer owes his advisors a total of $300,000, to be paid at closing. So in this example, Buyer needs to bring $20.5 million to the closing in order to make a $20 million acquisition.

The flow of funds statement in Figure 16-1 is severely simplified from the flow of funds statement you're likely to see in a real deal. In an actual flow of funds, you may see many more sources of funds; many more uses, such as fees the funding sources earn for providing the funding; and notations referring to Buyer assuming Seller's debt.

The flow of funds statement in Figure 16-1 is severely simplified from the flow of funds statement you're likely to see in a real deal. In an actual flow of funds, you may see many more sources of funds; many more uses, such as fees the funding sources earn for providing the funding; and notations referring to Buyer assuming Seller's debt.

Buying or selling a business doesn't simply involve transferring money from Buyer to Seller. In other words, Seller doesn't walk away from the closing with a pile of money and a pile of bills. Instead, the Seller pays off her debts, including debts to lending sources, vendors, taxing authorities, consultants, and any other creditor, at closing. In addition to debts, money for the escrow account is deducted from the sale price.

Figure 16-1:

A sample flow of funds statement.

In Figure 16-1, Buyer brings $20.5 million to closing. However, because Seller owes the bank and her advisors money and needs to put money needs in escrow, she actually receives only $11.79 million. Buyer wires that amount to Seller and also wires money to every other party that is due money at closing.

Buyers, make sure the Seller pays off all debt, especially any and all outstanding tax bills. In fact, Buyers should not close until every outstanding Seller debt is extinguished. If you assume control of a company and Seller hasn't paid off a debt, that creditor is liable to come after the company â in other words, the new owner: You. That's why Sellers usually are the ones who remit those payments (using Buyer's money) at closing.

Buyers, make sure the Seller pays off all debt, especially any and all outstanding tax bills. In fact, Buyers should not close until every outstanding Seller debt is extinguished. If you assume control of a company and Seller hasn't paid off a debt, that creditor is liable to come after the company â in other words, the new owner: You. That's why Sellers usually are the ones who remit those payments (using Buyer's money) at closing.