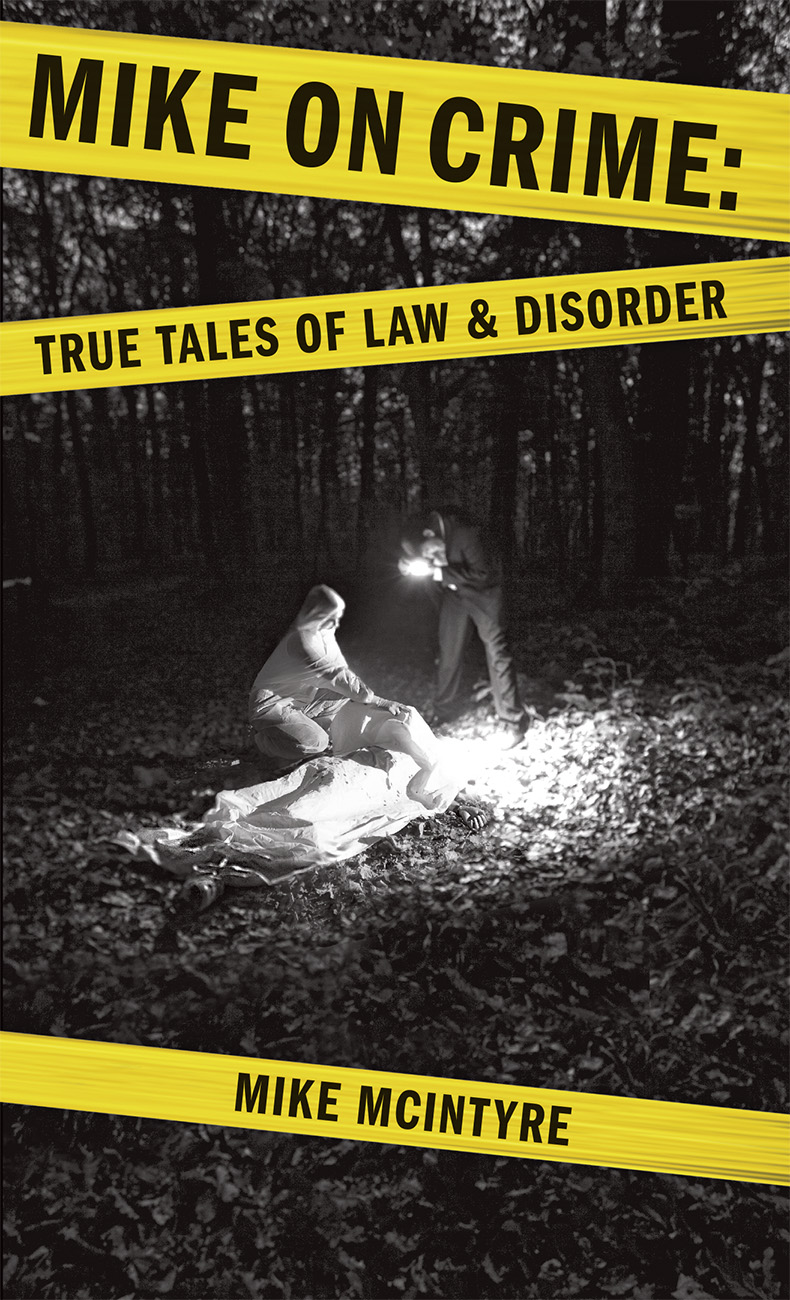

Mike on Crime

Mike on Crime:

True Tales of Law & Disorder

Mike McIntyre

Â

Â

Copyright ©2014 Mike McIntyre

Great Plains Publications

233 Garfield Street

Winnipeg,

MB

R3G 2M1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or in any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of Great Plains Publications, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a license from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), 1 Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario, Canada,

M5E 1E5

.

Great Plains Publications gratefully acknowledges the financial support provided for its publishing program by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund; the Canada Council for the Arts; the Province of Manitoba through the Book Publishing Tax Credit and the Book Publisher Marketing Assistance Program; and the Manitoba Arts Council.

Design & Typography by Relish New Brand Experience

E-book conversion by Human Powered Design

Printed in Canada by Friesens

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

McIntyre, Mike, author

Mike on crime : true tales of law and disorder / Mike McIntyre.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN

978-1-927855-06-5 (pbk.).--

ISBN

978-1-927855-07-2 (epub).--

ISBN

978-1-927855-08-9 (mobi)

1. Crime--Canada--History. 2. Criminals--Canada--History. I. Title.

HV6804.M37 2014 364.971 C2014-903359-1

C2014-903360-5

Â

Â

To Chassity, Parker and Isabella

Â

Â

Teacher. Meteorologist. Winnipeg Jets play-by-play voice. Accountant. Professional wrestler. Like most kids growing up, I wasn't really sure what I wanted to be when I “grew up.” But I certainly had plenty of ideas, some of which were admittedly far-fetched. I mean, an accountant?? C'mon!

It wasn't until late in my final year of high school that things began to come into focus, thanks largely to a meeting with a guidance counsellor. He helpfully suggested some of my interests and skills might be suited for the communications industry and pointed out a local post-secondary program that might be right up my alley. The rest, as they say, is history. Wonderful, memorable history.

I was accepted that year, at the tender age of 18, into the Red River College Creative Communications program. It is there I first developed a love for writing, especially of the non-fiction variety. Local news especially piqued my interest. Much of this was fostered by my incredible journalism instructor, Donald Benham. He helped chart a course for future successâone that included a fantastic work placement at the

Interlake Spectator

newspaper following completion of my first year of college. I covered it all that summerâlocal politics, crime, feature stories and all kinds of quirky tales about local residents. As I returned for my second year, my focus was clear. And the planets began to align in a way that I still look back and thank my lucky stars over. A three-week stint at the

Winnipeg Sun

would prove to be my big chance. They happened to have a job opening and offered it to me as I neared graduation in the spring of 1995, barely 20 years old. Incredibly, they weren't just offering me a job. They were offering me their prized beatâcovering cops and crime. Here I was, a wide-eyed kid who grew up on the not-so-mean streets of North Kildonan in Winnipeg, about to immerse myself in a crazy world I knew very little about. But like everything in life, I jumped in with both feet. And what resulted has been a wild, 20-year journey that I still find hard to believe at times.

I left the

Winnipeg Sun

after two-and-a-half years, taking a job opportunity at the

Winnipeg Free Press

to remain on the crime trail. I moved to the justice beat in 1999, parking myself down at the downtown Winnipeg Law Courts where I've remained ever since. I have a daily front row seat to some of the worst society has to offer. But I remain proud and passionate about my hometown. Whether it's sitting down with a grieving victim's family or staring down a criminal behind bars at Stony Mountain, I've always strived to get all sides of the story.

Preparing for this, my sixth true crime book, was an emotional experience. It required many long nights of going through old story archives, re-living many of the notorious cases I've covered and drudging up long-buried memories. All of what you will read in these pages is based on interviews conducted by me and colleagues, sworn testimony, first-person accounts from the courtroom, documents and exhibits filed in the hearings, parole documents and previously published newspaper stories and columns with full credit and attribution. No dialogue or scenarios have been improvised, assumed or re-created.

There are so many people to thank for the first 20 years of my career: Former teachers, editors and my extremely talented colleagues. Staff at the courthouse who have helped me in so many ways. Lawyers, judges and yes, even those criminals who have permitted me access. And all of those victims of crimeâthe survivors, the grieving family membersâwho have opened their lives to share their stories.

And, finally, my incredible supportive family. My parents, my wife and my two amazing children.

I believe the stories you are about to read are important ones which have helped shape the fabric of our community. It is a trip down memory lane well worth taking. Thank you for joining me on my journey.

Mike McIntyre

“BEEPER”

I

t was one of the first signs that Winnipeg had a major street gang problem. And it made headlines across Canada while sparking calls for tougher penalties for young offenders and tougher laws for organized crime members. But what I'll remember most about the following story is this: The sight of a lifeless boy on the pavement, the sounds of screaming and the utter chaos in the night air. Joseph Spence was the first dead body I'd ever seen in my life.

I arrived at the scene within minutes of his shooting, having been monitoring the police scanner along with another young reporter, Nadia Moharib, and photographer Chris Procaylo. All three of us were relatively new employees at the

Winnipeg Sun

and were keen to make a good impression on our bosses. And so we would often hang out at night, rushing to major calls to get first-person witness accounts and photographs. We were just a couple blocks away when this one was broadcast over the airwaves. But I was not prepared for what I saw that night. And the vivid memory of it continues to haunt me to this day.

SUNDAY JULY 23, 1995

Joseph Spence had spent the night playing video games with friends at his grandparents' residence. Now the 13-year-old Winnipeg boy, known to everyone as “Beeper”, was on his way to a nearby relative's home. It was 2:30 a.m. As he pedaled his bicycle through the city's gritty North End neighbourhood, Beeper and a small group of friends who were with him didn't seem to notice the blue van approaching from behind. Inside were three young strangers hell-bent on revenge.

As they approached the intersection of Flora Avenue and Robinson Street, one of the strangers put on a pair of gloves and then picked up a sawed-off shotgun. He wiped down the weapon several times, then picked up a shotgun shell and did the same. The van rolled up beside Beeper and his buddies. The window came down. The man with the gun yelled for them to come closer. Before anyone knew what was happening, he raised the firearm and pulled the trigger. The result was catastrophicâfor the young victim, the shell-shocked neighbourhood and the city at large.

It was an image Dale Wiltshire would never be able to forget. The 24-year-old off-duty Winnipeg police constable just happened to be driving down Flora Avenue, on her way to visit a friend, when she witnessed the sort of horrific event that no amount of training could have prepared her for. Beeper Spence had just been shot in front of her.

“It was the most horrible thing I've ever seen in my life,” Wiltshire would later tell colleagues. “I saw him fallâit was so close and so forceful it lifted him up in the air.”

She had only graduated into the police service one month earlier, but Wiltshire's instincts immediately kicked in as soon as the shot rang out and the victim went down. She jumped out of her vehicle. Her first thought was to reach for her firearm. But she wasn't in uniform, of course. She was unarmed. And scared. The suspect's vehicle had sped away, leaving behind a scene of utter chaos. Several of the victim's friends were screaming. Neighbours who heard the incident had come rushing outside. Sirens could be heard in the distance as police and paramedics rushed to the scene.

Wiltshire ran to the victim, instantly checking for a pulse. The damage from the shotgun blast was enormous. But the boy had briefly gasped for air, giving her some hope. Then the boy's breathing suddenly stopped. Wiltshire turned him over on his back and began giving him CPR. Her boyfriend, who had been with her in the vehicle at the time, helped as well. But all their efforts would be for naught. Beeper was dead.

They called him the “question boy”âan ode to the inquisitive nature of the Grade 7 student at David Livingstone School. But now those who knew and loved Beeper Spence were the ones asking questions. Why would someone kill the popular teen in cold blood?

The initial theory being looked at by police was gangs. Winnipeg was struggling to cope with an emerging street crime scene that had seen the formation of several factions in recent years. While highly disorganized, there was no disputing just how dangerous some of these individuals could be. So-called “turf wars” were beginning to develop, with each group trying to stake their claim of the lucrative drug trade. The result was a growing amount of violence, including numerous acts that weren't being reported to police but rather being dealt with by a form of street justice.

There were rumours circulating that Beeper himself was a member of the Indian Posse gang, which had quickly established itself as Winnipeg's biggest with more than 100 members. However, those closest to Beeper knew the truth: While he certainly knew members of the gang, he wasn't a member. But police believed those responsible for his death didn't know that. They were suspected members of the Deuces gang, which was known as the main rival of the Indian Posse. They were much smaller, with only about 30 known members. Several Deuces members had been attacked in recent weeks. And word on the street was that they were looking to settle some scores with the Indian Posse.

“This was retaliation,” one neighbourhood resident told the

Winnipeg Free Press

. She had witnessed the ugly aftermath of the shooting after being awakened by the shotgun blast just outside her front window. “You know it's not going to stop here. There's going to be more killings,” she predicted.

Beeper himself had expressed concerns about gangs in the area, specifically about guilt by association. Beeper was living with his grandparents on Sinclair Street but would spend weekends with his father and aunt, who lived near the scene of the shooting. His grandfather, Nick Grisdale, recalled how members of the Deuces had harassed the boy in the past, believing him to be a rival. Now it appeared they had done a lot more than just harass him. Beeper had been caught in the crossfire, the victim of a tragic case of mistaken identity.

Bright. Chatty. Happy-go-lucky. These were some of the terms being used to describe Beeper Spence in the wake of his tragic shooting death.

Rick Johnston was the coach of Beeper's peewee baseball team, called the Indian and Metis Friendship Centre Eagles. And he was now mourning the loss of a second player to violence. Last year, his star pitcher, Trevor Sanderson, was gunned down in a gang-related shooting, and now Beeper, another young hurler, had his promising life cut short. “It's maddening,” Johnston told the

Winnipeg Free Press

. “There's another one gone.” He said these types of senseless incidents were making him more determined than ever to get kids off the streets and into positive environments such as team sports. “It makes me want to fight even harder⦠I'm not throwing in any towels.”

Meanwhile, one of Beeper's former teachers was speaking out as well, saying this type of deadly attack was her worst type of fear come true. “I'm worried sick when the end of June comes. At least when they are at school, you know the kids are safe,” Anastasia Yereniuk told the

Free Press

. “I was just sick when I heard [about Beeper]. He was a nice kid, full of life.” She described the culture of violence that had seemingly taken over many of the youth she taught. “I can't say I'm surprised this happened,” she said. “They all hang around gangs here. It's a sign of the times in this area. The gang problems have never seemed as bad as they are now.”

MONDAY JULY 24, 1995

They gathered close together, more than 100 strong, as the sun began to set on another hot summer's day. It had been less than 48 hours since Beeper Spence was shot dead at this intersection. Now the boy's photo, pasted to a large piece of cardboard, rested against the tree. Mourners, many of them in tears, signed their names after touching the image of the slain boy. A blue blanket adorned with his photo and a flowery cross of tissue paper was also nailed to the tree. A Catholic priest said prayers followed by eulogies by three of the boy's friends.

“We just did it to show our love for him,” Beeper's mother, Nancy Flett, told the

Winnipeg Free Press

. She repeated the family's strong denials that Beeper had any kind of gang involvement: “The only colours he wore was the yellow T-shirt and baseball cap for the Winnipeg Boys and Girls Club.”

Meanwhile, police had made their first arrest. A teenage boy was picked up earlier in the day while walking down a North End street. He was now charged with first-degree murder, indicating justice officials believed this was a planned, pre-meditated act. Three more arrests would soon follow. And police admitted they were bracing for more potential violence. “We're kind of holding our breath and hoping for the best,” police spokesman Eric Turner told reporters. “There is definite concern we're in the midst of a very serious situation.”

Police were beefing up enforcement, and the 15 members of the street gang unit would be working overtime as they tried to keep a lid on any fallout or retaliation. “We'll be keeping an ear to the ground to see which way the winds are blowing,” said Staff Sgt. Caron.

“Moms and dads, where are your kids.”

Ken Biener was growing frustrated at what he felt was the lack of accountability being shown by many Winnipeg parents. And so the inspector of the police youth division was speaking out in the wake of Beeper's slaying, suggesting that allowing your young teen to roam the streets at all hours of the night was a bad idea. “I'm satisfied this is happening all over. But it's the element of risk for kids that is different. Let's face it, there are a lot of crusty things happening in the core area after dark,” Biener told the

Winnipeg Free Press

.

Beeper's family members were stinging at allegations on radio call-in shows and newspaper letters-to-the-editor that they must not have cared about the young boy. “It was just a short walk to his auntie's,” Nancy Flett explained. She repeated the story of how he and friends had been at his grandmother's, but then was asked to leave because it was getting late and they were making too much noise. So they were on their way to Beeper's nearby aunt's home.

She and husband Stanley Spence split when Beeper was four. But that didn't mean he was from what most people think of as a broken home, she said. “He was very well looked after, and he was well-loved by everyone,” said Flett. Meanwhile, she was now worried about the safety of her two other children, daughters aged 10 and 12, fearing there could be more violence to come.

“TIME FOR ACTION”

Editorial published in

The Winnipeg Free Press

, Tuesday July 25, 1995

The weekend shooting of 13-year-old Joseph Spence and the escalation of street gang violence in general raises the inevitable question: Can anything be done about it?

The answer is yes. The solutions aren't simple, nor do they necessarily entail the expenditure of vast sums of money on new programs or the hiring of civil servants to run them. They do, however, require leadership and commitment on the part of some politicians and community leadersâthe kind of leadership that has been lacking over the last few years.

Winnipeg has experienced a dramatic rise in youth related crimeâparticularly violent crimeâsince the start of the decade. Car thefts, purse snatchings, muggings and assaults are all up substantially over the numbers recorded just a few years ago.

Police attribute most of this increase to the growth and evolution of youth gangs in the inner city.

Indeed, police no longer refer to them as youth gangs; they're now called street gangs. The police say these gangs have become more organized and actually control federal and provincial jails in Manitoba.

And what were city and provincial government officials doing while the youth gang problem worsened?

Well, Justice Minister Rosemary Vodrey held a youth crime summit a few years ago and decided the solution was to talk about harsher sentences, boot camps and cancelling drivers' licenses of young offenders. The city, meanwhile, has done even less. As noted on this page last week, city council has given Mayor Susan Thompson a budget to hold conferences on youth crime, but nothing to help people actually do something about the problem.

In other words, the two levels of government closest to the issue have done virtually nothing.

Everyone knows why Winnipeg has a gang problem. Kids in the inner cityâmostly nativeâare growing up in poverty, sometimes without strong parental support and often with a sense of alienation and hopelessness.

Short-term solutions are obvious. The city and the province have to make youth crime a priority and develop and fund the kinds of programsâlike sports and recreation centresâthat can give community workers a fighting chance to reach kids before they get into trouble.

In the long term, the Filmon government has to address the underlying causes of youth crime. It has to develop programs that reduce child poverty and make these kids believe they can have a future. That means making sure they have an opportunity to get an education that will lead to a decent job. It also means building a society that is tolerant and open, one where native youths can feel included rather than excluded. If not, the problems of the inner city will continue to growâ and spread.

TUESDAY FEBRUARY 23, 1996

He hadn't pulled the trigger. But a Winnipeg teen would still have to pay for his role in the killing of Beeper Spence. The 16-year-old pleaded guilty to a charge of being an accessory after the fact to murder, admitting he hid the shotgun and spent cartridge that had been used to gun down the teen less than a year earlier. Judge Philip Ashdown gave the youth one year of jail in addition to six-months of time already served. He was also placed on 18 months of supervised probation. His name could not be published.

“You've taken my only son away from me. You sit here like it was nothing,” Nancy Flett said in a victim impact statement she read aloud. “[Beeper] can never sit with us around the Christmas tree, he can never go to school... still, you can do these things. Nobody said you guys could go out there and play God.”