Miles to Go (6 page)

Authors: Miley Cyrus

Hannah Who?

Hannah Who?W

hile we were taping the pilot, Disney let me know that there was just, ah, one more tiny little thing they wanted me to do. A concert.

(Yikes!)

That’s right—they wanted me to perform a concert as Hannah Montana in front of a crowd of people who had no idea who I was,

before

the show had even started.

(Double yikes!)

When the big night came, I was a nervous wreck. Sure, I’d been backstage, even onstage with my dad at plenty of concerts. But now there were new songs, new choreography, new dancers, props, and wardrobe changes. And no Dad. The focus was all on me.

The crowd at Glendale Centre Theatre—not far from the Disney studios—didn’t know who or what they were going to see. They just knew they were watching an unknown girl named Hannah Montana, and she had something to do with a new Disney show. And it was free. I’m sure some of those people wish they could travel in time and scalp those free tickets for big bucks.

(Not that I approve of that behavior!)

I couldn’t believe anyone showed up at the concert. Who wanted to see an unknown singer? When I started, I was scared that I would tank—and I felt stupid for pretending to be such a hotshot star when nobody knew who I was. It was so weird. Between songs, I’d whisper into the mike, “I’ll be right back,” and scurry off the stage like a little mouse to ask my mom and the producers if I was doing okay.

Then, around when I was singing “Pumping Up the Party Now,” I noticed that people were into it. They seemed excited to see the show. It gave me a second to pause (in my head—I kept singing, of course) and realize what was happening to me. It didn’t matter how odd and contrived this performance was. I thought to myself,

I’m happy to be here. I really am.

That was it. After that moment I started to get into my groove. I found out later that Gary Marsh, the president of Disney Channel, turned to my mom and said, “Didn’t take her long to settle in.”

By the end of the concert the audience was standing up, cheering, shouting “Han-nah! Han-nah! Han-nah!” I ran across the front of the stage. I high-fived them. I improvised. I just had fun.

It was really happening. This was my moment.

Some of that concert is still used in the show, sort of as if it’s Hannah’s music video. They use the footage from “Pumping Up the Party Now,” with me in my pajamas

(Hannah has grown up so much—she'd never perform in sleepover pj's now!)

, in the opening sequence and to promote the show sometimes.

And then the pilot was done, and they slapped braces on my teeth.

Losing Pappy

Losing PappyB

efore I get back to the braces, I want to talk about Pappy. While we were taping the pilot, Dad was flying back and forth between the set of

Hannah Montana

and my pappy’s bedside. Pappy was my grandfather on my dad’s side. He was sick, really sick with lung cancer, but all the amazing memories I have of him were in my head as I worked. I knew he wanted me to follow this dream.

Pappy had a log cabin in Cave Run, Kentucky. It is the most beautiful place on earth. In the morning, he’d make bacon for us and tell some crazy story about what the dogs were up to or what the neighbors said.

Each of us kids had a room upstairs in his cabin. Whenever we came to visit, I’d head up to my room the first night and he’d have positioned an old bearskin rug flat on the floor with its head popping up. It scared me to death every time. But that was Pappy for you. I loved his teasing. I even loved the way Pappy smelled. He wore the same deodorant for years—it’s a generic country brand—and now I keep it around because it reminds me of him.

We spent plenty of time in that cabin, just goofing around. I would change the outgoing message on the answering machine to say “Hey, thanks for calling my pappy,” and then I would blow a whistle that sounded like a train—

whoo whoo whoo

—and say, “I love him and hope you love him too.” (If you’d known him you would have.)

The cabin was near a mountain that had a cave. During the day, Pappy would help me, Brazz, and Trace (my sister Noah wasn’t born yet) look for arrowheads and scout for bats. Pappy was a giant kid. When we’d go fishing,

(Well, ... at least I went along until I got my foot stuck in a hole on the bridge and they had to cut me out before the catfish ate my toes. After that I wasn't so into fishing.)

Pappy would drive ahead of us in his old-man car and my dad would follow behind, driving way too slow, never able to keep up. Dad is usually a cautious driver (except when he’s behind the wheel of a dirt bike or a four-wheeler).

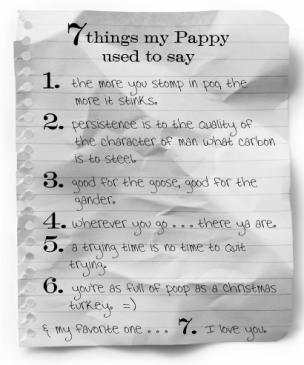

Pappy had a husky voice like me and a stomach that always stuck out a little—like he’d just had a big meal. He was always spouting folk wisdom that made no sense to some people, but it did to me (usually). If I was talking about someone who made me angry, he’d say, “The more you stomp in poo, the more it stinks,” or “When you knock ’em out, you don’t need no judge.” (That’s what he always told my dad because he used to be a boxer.) When I was wearing something—say, a hat—I’d say, “Don’t you like my hat, Pappy?” If he didn’t like it he’d say, “Oh, sure, I’d like to have two of them. One to crap on and the other to cover it up with.” Then my dad would chime in, “Yeah, me too.” And I’d say, “I have no clue what either one of you is talking about.” It didn’t matter, though. He was just the best granddad I can imagine.

Pappy was always a good audience. The staircases in his cabin led to an upstairs loft, and when I was a little kid—five or six—I’d put on a show, belting out “Tomorrow” from

Annie

as I came down the stairs. Pappy would clap and whistle and say, “Go on up there and do it again.” I ate it up. And when I was at the cabin, I always played his piano. I never took piano lessons, but I liked—and still like—letting my fingers tinkle around the keys. Pappy called that tinkling “The Rain Song.”

That’s how I ended up writing the song “I Miss You” for Pappy.

He was so sick. I knew he was dying, and slowly so did my heart. I couldn’t imagine life without him. It was the hardest song for me to write. I was working on it with my mom’s good friend Wendi, and it was just killing me. Finally I said, “I can’t write anymore. I gotta stop.” But I knew what my heart wanted to say, and whatever’s in my heart finds its way to my fingertips. So we pushed on and finished the song. I really wanted Pappy to hear “I Miss You” before he died. I never got to sing it for him, but toward the end my dad played Pappy a quick cut of the song, and I like to believe that it gave him hope, like he continues to give me hope.

Pappy said he refused to die before

Hannah Montana

aired on TV for the first time, but he passed away two days before the premiere. Still, he did get to see a tape of the pilot. I know he was proud.

In the South, funerals are like weddings. Everyone shows up in big hats to gossip and pay their respects. It’s practically a family reunion. At Pappy’s funeral I couldn’t see anything but my granddad. There was an open casket and I wanted to touch his hand one last time, to say good-bye. But I didn’t want to remember him that way, so I stayed back. That moment still haunts me.

After Pappy died, I kept circling around his death. If you’ve lost a grandparent, maybe you know how that goes. I missed him. I still do. I mourned him. I still do. I kept thinking about how I promised I’d let him take my older sister Brandi and me to King’s Island (an amusement park), but never got a chance. I got stuck on the times I didn’t talk to him on the phone. There was a voice mail from Pappy saved on our answering machine, and I listened to it over and over again, because every time it brought him back as if he’d never left.

Then I had a dream. It was Pappy, wanting me to move on.

He said, “I can’t leave with you holding on so tightly. You can’t let my death stop your life.” When I woke up, his voice was so alive in my head it was as if he’d just said good-bye and walked out the door. Out of habit, I went to the phone to listen to his voice mail. It was gone. Deleted. Floating away out into the ether. As though Pappy was telling me to let go.

My dad has taken over Pappy’s tendency to talk in gibberish. He’ll say “What’s good for the goose is good for the gander.” The other day he said “spigot” instead of “faucet,” and the way he said it was just like Pappy: “spicket.” And I finally saw that it doesn’t matter if I let go of Pappy. He’ll always be with us.

Believe

BelieveJ

ust because they shot a pilot—the first episode of the show—didn’t mean

Hannah Montana

would ever see the light of day. Lots of executives had to decide if it was good enough. If they approved it, then they’d “pick it up.” That meant we’d make more episodes, and the show would go on the air. Which was what we all wanted.

We were back in Nashville when the news came that

Hannah Montana

had been picked up for thirteen episodes. Disney wanted me in L.A. in seven days. Seven days! My mom didn’t want to uproot the whole family so quickly without putting us in a place that would feel like a home. She didn’t want the move to be hard or to feel like a sacrifice for my brothers and sisters. My mom is like that. She isn’t the type to get caught up in Hollywood or the idea of my being a star. She always thinks about the big picture. The whole family. How we can be stable and normal. Mom went online and bought the smallest house in La Cañada she could find. Just like that. As if it were a T-shirt from a catalogue. Mom is so twenty-first century.

One of the first things we did when we arrived in L.A. was to go to the Disney offices to say thank you. We had lunch with my agents, then drove in a convertible to Disney. My dad and I always rode four-wheelers around our farm, redneck style. This was the opposite end of the top-down experience. Wasn’t I glamorous in my convertible? A TV star, on her way to thank the producers. Except when I walked into Gary Marsh’s office, a look of horror crossed his face. “What happened to you?” he asked. Riding in the convertible hadmessed uprestyled

my hair. Which was dyed a weird blond color. I’d had two teeth pulled. And oh yeah, the braces. I had braces. It was not a pretty sight. I got off my high horse pretty fast.

The hair went back to brown. The braces came off. I got a little retainer with fake teeth to fill in the holes while my grown-up teeth grew in.

(I called it my flipper.)

That was my first perk as a TV star: having an excuse to ditch the braces.

After they “fixed” me, there was still more to accomplish before we started shooting the series. They had to do my wardrobe. I had go into a studio to record music for the whole first season. Oh, and they had to fit me for wigs. The pilot wig was a joke. Now I would get real, expensive wigs that were molded to my head. If you’ve never experienced a wig fitting, let me tell you—it’s not very glamorous. They put you in a wig cap, which is like a swimming cap made of stocking; they put Scotch tape all around it until it’s a hard form; then they use that to make a mold.

(Having a wig made: every girl's dream!)

Wigs done, the series got rolling. Soon after, there was a party at the set for the premiere of the show. Emily and I both wore black dresses. We were so excited to watch the final version of the pilot—the version that millions of viewers would watch on Disney Channel. We hoped.

The show was far better than I expected it to be. You say a line six times, sixty times, and you end up with no idea which one they’ll pick in the editing room, how it will sound, and how you’ll look saying it.

You sing a song in a studio and only imagine how it will come out with sound production and lipsynching. But there we were, up on screen. Me, Dad, and all my new friends. I have to say, I thought we were pretty awesome. No matter what happened, that moment was mine, and I will never let it go.

The very next day I went to an amusement park with my aunt. We weren’t thinking about the show. We had no idea what the ratings were. It didn’t occur to us that people had actually seen my face on television the night before. We were on our way to the roller coaster, when six thirteen-year-old girls ran up to me and asked me for my autograph.

(No lie!)

I did an internal roundoff–back handspring–backflip for joy! “Sure!” I said, so hyperenthusiastically that I’m pretty sure I scared my very first fans (who were taller than I was). That was the moment when I realized that

Hannah Montana

wasn’t just a new job that I loved. There were people out there watching us. Real people, who recognized me on the street. I wasn’t just Miley Cyrus anymore. I was carrying Miley Stewart and Hannah Montana around with me. It was weird. It was cool. I was twelve.

Haven’t you practiced your signature in school notebooks or when you’re talking on the phone? I have. Page after page where I should have been taking notes is covered with my name, accompanied by all different doodles and flourishes. I knew how to sign my name, but what else did I want to tell these girls, my first fans? I thought back to what I would have wanted to hear when I was just one of fifty Hannah Montana wannabes sitting nervously in a waiting room. I thought back to what I would have wanted to hear when I was crouched alone in the school bathroom, at the end of my rope. I thought back to what my fish would have wanted to hear after his best friend bit the dust. Now I knew exactly what I wanted to write. I took a long time with those first six signatures, making sure I did them perfectly.