Millions Like Us (60 page)

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

A great amount of breast-beating and soul-searching ensued about

the future of the family – and civilisation itself. Government and the church wrung their collective hands over the nation’s moral laxity and the spread of immorality. For hundreds and hundreds of years, men and women had thought they knew where they stood. Had the war dealt that certainty a death-blow?

A la Recherche

From the evidence, both sexes still looked to an idealised past, hankering after a half-remembered world of grace and gallantry, of clinging subordination and virile authority.

But could it ever return? Had too much changed? To many women, the world of 1946 was an alarming and dangerous one, one which was fast eroding their sense of who they were. Hardship and worry were their daily lot, relationships were being tested as never before, the institution of marriage appeared to be spiralling helplessly into crisis, their homes, their roles, their sense of meaning, their whole world seemed to have been exploded. Life was ‘all wrong’.

They longed above all to rebuild the remembered past amid the wreckage of the present – in the case of Madeleine Henrey and her mother, almost literally.

Shortly after the liberation

of France, Madame Gal decided that the time had come to retrace her steps from Paris to the farm in Normandy that she had shared with her daughter Madeleine, her English son-in-law and Bobby, her baby grandson. The region was still littered with the charred traces of battle, and it was a difficult journey. Mme Gal walked into the house and nearly fainted from the stench that met her nostrils; the rooms had been vandalised and stripped of their contents. Cobwebs were everywhere. Ripped-out pages from Madeleine’s copy of the New Testament, desecrated with human faeces, lay in festering heaps in the downstairs closet. ‘What barbarians had passed this way?’ Gradually, she pieced together what had happened; Germans and local looters between them had defiled her daughter’s property and stolen every stick.

Patiently and courageously, Mme Gal set about the slow task of cleaning the farmhouse. Every day that passed she made a little progress; in the evenings she knitted a patchwork quilt from scraps of

wool and wrote to her daughter in England. VE-day came and went; Madeleine herself was still unqualified for a travel permit, but whatever she could afford in the way of tea-leaves, soap or chocolate she sent to her mother. Neighbours brought eggs and butter. In anticipation of autumn Mme Gal made jam from the fruits of summer, gathered faggots from the wood and stored charcoal for the stove. At last, in September 1945, Madeleine’s papers came through. Torn between anguish at leaving her husband and six-year-old Bobby and the joyful prospect of a long-awaited reunion with her mother, she set off for France.

Madeleine would have to travel to Villers-sur-Mer via Paris. She took with her as much food and clothing as she could carry. Victoria Station was a seething Babel of foreign servicemen and charging porters; the train reached Newhaven at midnight. On the channel steamer Madeleine shared a cabin with a young Englishwoman travelling back to be with her French engineer husband. They talked of living through the air raids, and of the occupation. It was a squally crossing. The arrival at Dieppe next morning brought back memories of the 1942 raid: ‘The vessel cut through the swell towards the land where men fell that it should be liberated … In a few moments I would once again step on French soil.’ After endless formalities, Madeleine was able to board the Paris locomotive – ‘had it been chased by Spitfires?’ As they chugged out of Dieppe she caught glimpses of destruction: a half-sunken vessel emerging from the low tide, bombed pillboxes and blockhouses. The train gathered pace through a countryside blitzed and scarred: roofless station buildings, twisted girders replaced by Bailey bridges, blasted track. At last, a magical sunset view of the Eiffel Tower, untouched in its glory, and they were in the capital.

Three days later, after ingenious machinations with the British Embassy had secured her a lift by road as far as Lisieux, Madeleine was on her way down the long poplar-lined arteries of France; speeding by the half-concealed wreckage of Tiger tanks rusting in ditches, the broken fuselage of a fighter impaled on the apex of a shattered farmhouse, two incinerated military trucks concertinaed into a burned-out tree trunk and an occasional destroyed aerodrome. Lisieux, when she arrived, was whitened rubble. From there she was collected by a neighbour from their village.

We drove rapidly across the plateau by way of Blonville, and as we approached … I felt my heart thumping against my ribs. I was longing to catch sight of my own land.

My mother stood framed in the entrance of the half-timbered house …

I ran into [her] arms.

That evening Madeleine and her mother walked together through the ripening orchards and out on to the high ground with its panorama over the Le Havre estuary. Here in June 1940 she and Robert had watched the invading Germans dropping bombs on the port, the day before their flight to England.

What bitter, poignant memories were revived by the sight of this orchard, where [the] cows moved gracefully in the long grass, and where the hedges were filled with ripening hazel-nuts. The red autumn sun was breaking through the haze, and all was peace and content.

So much had passed, so little had changed.

But now there was work to be done. Madeleine became busy; she organised carpenters to do repairs and decorators to restore colour and brilliance to the house. She had the furnace overhauled and the windows reglazed; she begged and bartered for furniture and bedding; she dug the garden and got the cattle pond cleaned.

As the year wound to a close Madeleine cut holly boughs, shook the icicles off them and carried them into the house for Christmas; her clogs clattered on the clean stone flags. Madame Gal was warm by the fireplace, tending a cafetière perched in its embers. The house smelled of lavender, burning logs, toast and coffee. Here, together, she mused, the two of them, mother and daughter, had wrought a miracle rebirth, an apotheosis of all that was womanly, maternal and good. The rescue of her farm from the spoilers and wreckers was an act of female creation. ‘The war was over and I had lived to see my farm handed back to me. Dreamily I thought about the future.’

I still felt a young enough woman to brave new ventures … Life had so many beautiful experiences to offer … I was thankful for my femininity … How would the next so important phase of my womanhood work out?

Down by the shore, the village church bells chimed the angelus.

For Madeleine, the war was truly over.

12 A Bitter Time

‘A Fine Type of British Girl’

London, April 1946. On a sunny afternoon

the romantic fiction author Miss Florence Speed

strolled from her home in Brixton to Kennington Park and sat down on a bench in the walled garden to read her book and enjoy the daffodils. A group of small children were playing like puppies under the plane trees, yelping with happy laughter. Bees buzzed. On a day like this, the terrifying, deafening doodlebug raids which almost two years earlier had wrecked her sleep, night after night, seemed a distant memory. There was surely no more perfect way to relish the return of peace than to soak up the sunshine in a London park.

But Florence had barely read a couple of pages when a middle-aged lady arrived, sat down heavily on the seat beside her and started to grumble. This person was seething with indignation about the world. ‘Disgusting,’ she said, indicating the happy band of youngsters, ‘that children are allowed in here. They’re so noisy and destroy everything.’ And she spewed out a catalogue of complaints, starting with a description of a recent bout of ’flu from which she was recovering, proceeding on to her high blood pressure and thence moving into a litany of the various things of which she currently disapproved, including the government, Mr Bevan, food shortages, children in general and the young women of today. She also took a low view of America – ‘a horrible, dirty’ place, in her opinion. ‘It’s a nice country – to get out of,’ she declared. ‘The GI brides are in for an eye opener.’

*

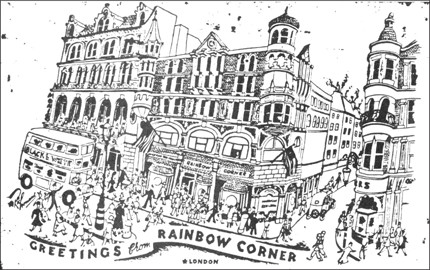

Three months earlier,

on the evening of Tuesday 8 January, a mob of those reprehensible young women had besieged the building on the corner of Shaftesbury Avenue known as ‘Rainbow Corner’, screaming and weeping, as a little bit of the USA in London shut up shop for the last time. Since November 1942, the club had entertained 18 million

American servicemen. Now, with the GIs heading for home, there was to be a final dance: the last jives would be jived, and the last jitterbugs jitterbugged. Eleanor Roosevelt, Anthony Eden and a starry line-up of performers were invited to attend. But the crowd was so dense outside that officials had to force a passage for the celebrities to enter. Many members of the public had climbed on to windowsills and lamp-posts to get a better view of the floodlit entrance. Traffic had to be diverted. A swarm of servicemen, policemen, hysterical girlfriends, passers-by and ‘Piccadilly Commandos’ became locked in a seething mêlée that see-sawed back and forth outside the club; fights broke out, and one woman fainted. The planned finale, with a band playing in the street, had to be abandoned; instead, they struck up their patriotic tunes, ‘Auld Lang Syne’ and ‘The Star-spangled Banner’, from the safety of a balcony. There were frantic goodbyes; many broke down. At midnight an American soldier came out and concluded the proceedings by nailing a board to the doors which for three years had never closed. It read:

OUT OF BOUNDS TO TROOPS

The emotion surrounding Rainbow Corner’s final hours is evidence of the place that 2 million young Americans now held in many British women’s hearts. Despite the culture clash, and for all their brashness, impudence and noisy lust, the sexy, well-heeled, smart-uniformed GIs had marched straight into the affections of innumerable British women.

More than 100,000 of these had married

their American sweethearts. Witnessing their forced departure was an occasion for mass heartbreak; but, nothing daunted, the GI brides were determined to follow soon after.

From early after the end of the war – October 1945 – British brides of US servicemen had been clamouring to be reunited with their departing husbands. But priority had to go to demobilising the men first; the wives could follow when there was spare shipping capacity. This didn’t go down well. Thousands of frantic brides from Wales, Scotland and the north of England travelled to London to demonstrate in Westminster. Many were heavily pregnant or with small babies, arm-in-arm, chanting ‘Yankee Doodle Dandy’ and ‘We Want Boats!’ There was hysteria, and fights broke out on the steps with policemen.

‘Goodbye, Piccadilly …’: Rainbow Corner, the US servicemen’s club, closed its doors for the last time on 8 January 1946.

Getting the war brides resettled with their new husbands in America and Canada was one of the challenges faced by authorities attempting to reorder post-war society. It was a bureaucratic swamp, involving visas, immigration laws and transport quotas. Every war bride had to demonstrate that she had the right documentation, and enough money to cover her railroad ticket. Then she – and her baby if she had one (and many did) – had to be processed through an ex-military camp at Tidworth near Southampton, where each woman was required to strip and line up to have a torch shone between her legs to check for VD. If she passed this humiliating medical examination she would be permitted to embark for the New World.

At last, on 26 January 1946, the SS

Argentina

set sail from Southampton. It was followed on 5 February by the

Queen Mary

;

Victoria Stevenson,

a reporter with

Woman’s Own

, joined 2,000 young ‘Pilgrim Mothers’ (as the press named them) and 600 babies, packed on board like sardines: a veritable floating nursery. ‘Many of the girls had never been to sea before,’ Stevenson told her readers, and went on to paint a heart-warming picture of ship life for the happy brides, who included a nurse, a dress designer, a psychology student, a riveter and an ex-clippie. The American government official chosen to accompany them described them as ‘a fine type of British girl’. Stevenson

went to see a cheery crowd of young women in an eight-berth cabin, ‘creaming their faces and curling their hair’:

Occasionally a tear was dabbed away as they spoke of partings with their home folk, then a love-letter or a photo of their new home would be produced, and their thoughts raced ahead to the man they each loved and for whose sake they had uprooted themselves.

Knowing how many more brides were due to follow in their footsteps,

Woman’s Own

went out of its way to present an upbeat picture of what had been dubbed the ‘Diaper Run’. There were descriptions of the jolly laundry rooms, frequented by busy throngs of women wringing nappies or getting their babies’ clothes aired. Fatherly stewards helped out with feeding bottles, resident Red Cross workers were on hand to help with all queries; sing-songs, religious services and instructive talks about America were organised.

But Elizabeth Jane Howard,

who was not a war bride, but had boarded the

Aquitania

with her British husband in spring 1946 along with 400 of them bound for Halifax, Nova Scotia, saw no cause to be upbeat: