Millions Like Us (9 page)

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

It Couldn’t Happen to Us

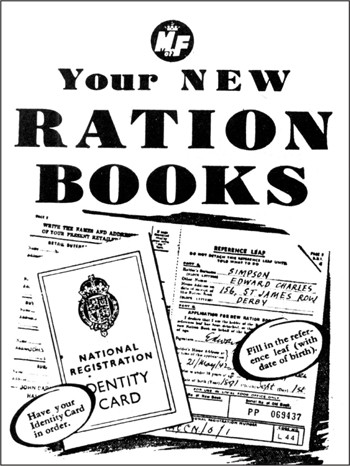

On 8 January 1940 the government introduced food rationing. The lack of shipping space for food cargo made restrictions inevitable,

and everybody knew it was coming. The ration books were ready. Towards the end of 1939 people had been told they must register with their chosen suppliers. Now every person was allowed four ounces of bacon, four ounces of butter and twelve ounces of sugar per week. In a matter of weeks butchers’ meat was also put on the ration: no more than 1s 10d-worth a week for each adult, 11d-worth for each child under six, not including offal. Fish was unrationed, but scarce.

From the start food rationing was seen as tough but fair.

The effects were felt straight away. In her Midlands village

Clara Milburn was exasperated

when her usual meat delivery failed and she and her husband Jack had to survive on larder remains. Mrs Milburn was a stern patriot, however, so when, eventually, a small boy appeared on a bicycle, bearing with him an even smaller joint, she reminded herself that restraint was a duty:

Such little joints, too, these days … It is a good thing to get down to hard facts, though, and make everyone come under the same rule and help to win the war …

We have a wicked enemy to encounter and there is only one way of dealing with so ruthless a foe, and that is to fight him until he is beaten.

Clara’s fierce patriotism was driven by a personal motive. As a Territorial, the Milburns’ only son, Alan, aged twenty-five, had been called up early in September 1939. He was now in France with the British Expeditionary Force, from where his intermittent letters were impatiently awaited by his anxious mother back in Balsall Common. Every week she mailed him biscuits, cakes and other small comforts. For her, as for so many, the fate of the army was her son’s fate; defeating the Nazis meant defeating those who wished him harm. Alan was never out of her thoughts; for his sake, we had to win the war. No wonder that her resolve to make any sacrifice, or comply with any order that might assist in the eventual triumph over his enemies, was unwavering. It was a resolve due to be severely tested.

This focus on Alan didn’t prevent Clara from intently following the course of the war in Finland that arctic winter, as the Russians advanced against a fiercely resisting nation until March 1940. ‘The news of the Finns is not good … We have sent aeroplanes, medical supplies, ambulances, clothes and money, and still they cry in their agony,’ she wrote. Finland capitulated to the Soviet aggressors on 12 March.

The freezing winter was followed by a ravishing and balmy spring. In early April Mrs Milburn walked Twink down to the corner baker’s and was pleased to notice that they were still selling biscuits, though ‘fewer cakes than in pre-war days’. On Monday the 8th she went to see Deanna Durbin in

First Love

at the Regal. The following day she heard on the radio that the Nazis had invaded neutral Norway: the next phase of the war had begun, Norway’s fate precipitating Winston Churchill into the premiership on 10 May. ‘The most eventful day of the war!’ wrote Clara. She and Jack had been up early. At 8 o’clock they switched on the radio, continuing to listen at intervals all day. The political convulsions were matched by those abroad, as the war now escalated into the Low Countries. Another diarist, later

the novelist Barbara Pym

, tried to analyse her feelings about the events of that day:

Friday 10th May

Today Germany invaded Holland and Belgium. It may be a good thing to put down how one felt before one forgets it. Of course the first feeling was the usual horror and disgust, and the impossibility of finding words to describe this latest

Schweinerei

by the Germans. Then came the realisation that war was coming a lot nearer to us – airbases in Holland and Belgium would make raids on England a certainty … I think I was rather frightened, but hope I didn’t show it, and anyway one still has the ‘it couldn’t happen to us’ feeling … Winston Churchill will be better for this war – as Hilary [her sister] said, he is such an old beast! The Germans loathe and fear him and I believe he can do it.

On 14 May Rotterdam was obliterated by bombs. The Belgian border with France was the next obstacle ahead of the Nazi advance, which for Clara Milburn meant only one thing: would Alan’s regiment, stationed in France, cross the border into Belgium? If so he would find himself in dreadful peril. The new Prime Minister’s unambiguous message resonated with Mrs Milburn: ‘You ask what is our aim? I can answer it in one word, VICTORY.’

Warm spring day followed warm spring day. The Milburns worked in their garden. The war news grew ever more grave, as Allied troops pulled back. Alan’s twenty-sixth birthday fell on 18 May. The night before, just as she was dropping off, Clara had the sense of a visual image pressing against her closing lids. She saw a face, which at first she couldn’t identify; fighting sleep, she attempted to focus on the features before it faded from her vision. For a moment it cleared, before being lost to the shadows: it was Alan.

On the morning of his birthday she pedalled into Balsall for their rations, pinned a poster discouraging waste on to the WI notice-board and returned to her gardening. ‘All day long we were thinking and talking of Alan, recalling other birthdays when he was a little boy and invited the three dogs to tea in the nursery!’

*

Refugees from the Low Countries were starting to arrive in London.

Frances Faviell went

to Chelsea Town Hall and offered her services as an interpreter. Among Frances’s many talents was an impressive linguistic ability. She spoke Dutch, having lived in that ‘kindly, tolerant’ country for more than two years; its language was closely similar to the Flemish tongue, and she was confident that she could help. The people’s plight tore at her heart; here, for the first time, was the desperate human face of war: terrified, frozen, sick and shocked. Inevitably, the majority were women with children. They had fled to

the ports and begged for a place in any boat which would have them. Now it was Frances’s task to explain as far as she could what would happen to these unhappy refugees. At Dover the stalwart women of the WVS had seen to their immediate needs: hot drinks, blankets, first aid. In London an appeal had been answered with donations of clothes and other domestic essentials. Frances helped with their distribution, before taking on the next job of cleaning the disused houses allocated to them. She and a group of volunteers got pails, soap and brushes, and spent several days on hands and knees scrubbing them out. Soon the Flemish women under Frances’s care were clothed and housed; from now on she would share her time between refugee duties and the first aid post for which she had trained.

At the FAP there were quiet times when she could draw or read. But helping the displaced women fleeing from their ruined lives left Frances Faviell with very little time to herself, and from now on she laid all thought of her work as an artist to one side.

Joan Wyndham, aged seventeen

, was of another type, breathlessly and insatiably interested in her own love life and the artistic milieu which furnished it. So on 1 April 1940, eager for new experiences, she signed up at Chelsea Polytechnic to study Art. From the outset everything looked extremely promising:

the students began to arrive: young men slouched in with hair flopping over their foreheads, lots of well-developed healthy girls with flat feet, in dirndls and brightly checked blouses. They fell on each other’s necks with cries of ‘Nuschka darling!’ or ‘Bobo!’ and so on …

– kindred spirits, clearly.

That spring, as the home front accustomed itself to the new rations and feverishly listened to the bulletins, Joan was modelling clay under the tuition of Henry Moore, attending life-drawing classes and adoringly pursuing Gerhardt, the moody German sculptor she had met at a party the previous autumn. ‘I would die for him tomorrow.’ Gerhardt was non-committal, but there were distractions: Jo, proprietor of the Artists’ Café, for whom she felt ‘a certain tenderness’, and Rupert – ‘devastatingly attractive’. Anyway, there were serious worries about Gerhardt, who was fearful of being interned. ‘If I’m not … and the Germans come, will I be able to shoot myself before they can get me? You know of course that I am Jewish?’

Gerhardt also took time to advise Joan: ‘You know it’s time you went to bed with someone.’ Since this well-intentioned recommendation appeared not to include him, it spelt the blighting of all her hopes. On 14 April she wrote: ‘I wish I was dead.’ But flirting with Jo, art school and drunken studio parties made life bearable. As Churchill’s leadership hung in the balance at the beginning of May, Joan found a new interest: Leonard, a painter who wore green trousers and sandals and explained to her about masturbation. But he wasn’t moody and handsome enough to be Joan’s type, so when he started groping inside her blouse she made her excuses and left. Instead she drifted back to Gerhardt’s studio – if he couldn’t love her, perhaps he could be her friend? That bright May afternoon everything was bursting into bud. As the sun dropped they stood on the balcony overlooking the Chelsea treetops. The vast blimps bobbed in the night sky, while across the Channel the German juggernaut was crushing everything in its path. ‘I don’t think they’ll ever raid London,’ said Gerhardt.

With Gerhardt off limits, Joan got her sex education where she could. She had her breasts caressed by Jo from the café; then there was an energetic kissing session with Leonard, who was amazing when it came to sheer technique. Though she turned down an offer to touch his penis, Leonard was a fund of information, demystifying orgasms, fellatio and unusual sex positions ‘with scholarly enthusiasm’.

Monday 27th May

The Germans are in Calais. I don’t seem to be able to react or to feel anything. I don’t know what’s real any more …

The bombs, which I know must come, hardly enter my fringe of consciousness. Bombs and death are real, and I and all the other artists around here are only concerned with unreality. We live in a dream.

Joan Wyndham’s frank introduction to the facts of life place her in a minority, but the dreamlike, dizzying quality of those days was shared by many. During the Phoney War bombs and death had seemed remote; but in spring 1940 they were remote no longer, and everyone was talking about invasion.

In the Face of Danger

Urgent times demanded urgent responses. ‘

Everyone is getting married

and engaged,’ wrote one young diarist in April that year, while also recording the reaction of a columnist in the

Daily Express

, that ‘any girl [who] ends up in this war not married … is simply not trying.’

In 1940 there were 534,000 weddings: nearly 40,000 more than in the previous year, and 125,000 more than in 1938. The brides were younger too – three in every ten were under twenty-one. At this time, before men’s long absences abroad made nuptials impossible, there was a peak in the phenomenon of the hasty war marriage. The world seemed so full of danger that prudent delay simply looked pointless – you could be dead if you waited till tomorrow, so better to seize the day.

Randolph Churchill

, son of the Prime Minister, set the tone. As he hurtled round the revolving doors of the Ritz he managed to get the friend galloping through in the opposite direction to give him a phone number for a blind date. He rushed to the phone, called the number and promptly inquired of the young lady who picked it up what her name was and what she looked like. ‘I’m Pamela Digby … Red-headed and rather fat, but Mummy says that puppy fat disappears.’ Churchill was charmed. Three days later they were engaged, and within a month they were married. No wedding bells, however, as that would have signified a German invasion.

Margery Berney was another

young woman who launched hastily into marriage at this time. Ignoring the promptings of ambition – for since childhood Margery had known she would

be

somebody – she took the conjugal plunge with an army officer named Major William Baines after an exceptionally brief courtship. Their wedding was followed by an equally brief few months together before her major was posted abroad. ‘People become reckless in the face of danger,’ was Margery’s only comment on their impromptu commitment.

Seizing the day might turn out all well and fine, but war weddings were often beset by worries as to whether both parties would actually make it to the ceremony. In the emergency climate of spring 1940 the forces refused to release their men for leave under any circumstances. On 10 May, the eve of her planned wedding to Victor, her RAF

sweetheart, young

Eileen Hunt made her way

to King’s Cross to meet him, only to find the station closed and swarming with police and soldiers. All leave had been cancelled; there would be no wedding. Heartbroken, clasping her bouquet of lilies-of-the-valley, Eileen went home and cancelled church, car and flowers. But her brother and Victor’s brother were not so easily deterred. They rushed up to Victor’s base near Cambridge, kidnapped him and hid him on the floor of a borrowed van, which they then drove at breakneck speed back to London. Eileen’s plans went into reverse; she put on her bridal gown and hastened to the church, where Victor appeared, and they were married without more ado. There was just time for the family to toast the couple, before Victor was bundled back to Cambridge and sneaked into his camp. A month later Victor and Eileen finally managed to get some time alone together – at the start of what was to be forty-nine years of marriage.