Miracles of Life

Authors: J. G. Ballard

An Autobiography

J.G. Ballard

Shanghai to Shepperton

An Autobiography

To

Fay, Bea and Jim

I was born in Shanghai General Hospital on 15 November

1930, after a difficult delivery that my mother, who was

slightly built and slim-hipped, liked to describe to me in

later years, as if this revealed something about the larger

thoughtlessness of the world. Over dinner she would often

tell me that my head was badly deformed during birth, and

I feel that for her this partly explained my wayward character

as a teenager and young man (doctor friends say that there is

nothing remarkable about such a birth). My sister Margaret,

born in September 1937, was delivered by Caesarean, but I

never heard my mother reflect on its wider significance.

We lived at 31 Amherst Avenue, in the western suburbs of

Shanghai, about eight hundred yards beyond the boundary

of the International Settlement, but within the larger area

controlled by the Shanghai police. The house is still standing

and in 1991, when I last visited Shanghai, was the library of

the state electronics institute. The International Settlement,

with the French Concession of nearly the same size lying along its southern border, extended from the Bund, the line

of banks, hotels and trading houses facing the Whangpoo

river, for about five miles to the west. Almost all the city’s

department stores and restaurants, cinemas, radio stations

and nightclubs were in the International Settlement, but

there were large outlying areas of Shanghai where its

industries were located. The five million Chinese inhabitants

had free access to the Settlement, and most of the people

I saw on its streets were Chinese. I think there were some

fifty thousand non-Chinese – British, French, Americans,

Germans, Italians, Swiss and Japanese, and a large number of

White Russian and Jewish refugees.

Shanghai was not a British colony, as most people

imagine, and nothing like Hong Kong and Singapore, which

I visited before and after the war and which seemed little

more than gunboat anchorages, refuelling bases for the navy

rather than vibrant commercial centres, and over-reliant on

the pink gin and the loyal toast. Shanghai was one of the

largest cities in the world, as it is now, 90 per cent Chinese

and 100 per cent Americanised. Bizarre advertising displays

– the honour guard of fifty Chinese hunchbacks outside the

film premiere of

The Hunchback of

Notre

Dame

sticks in my

mind – were part of the everyday reality of the city, though I

sometimes wonder if everyday reality was the one element

missing from the city.

With its newspapers in every language and scores of radio

stations, Shanghai was a media city before its time, celebrated as the Paris of the Orient and the ‘wickedest city in

the world’, though as a child I knew nothing about the thousands

of bars and brothels. Unlimited venture capitalism

rode in gaudy style down streets lined with beggars showing

off their sores and wounds. Shanghai was important

commercially and politically, and for many years was the

principal base of the Chinese Communist Party. There were

fierce street battles in the 1920s between the Communists

and Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang forces, followed in the

1930s by frequent terrorist bombings, barely audible, I

suspect, against the background music of endless night-

clubbing, daredevil air shows and ruthless money-making.

Meanwhile, every day, the trucks of the Shanghai Municipal

Council roamed the streets collecting the hundreds of bodies

of destitute Chinese who had starved to death on Shanghai’s

pavements, the hardest in the world. Partying, cholera and

smallpox somehow coexisted with a small English boy’s

excited trips in the family Buick to the Country Club

swimming pool. Fierce earaches from the infected water

were assuaged by unlimited Coca-Cola and ice cream, and

the promise that the chauffeur would stop on the way back

to Amherst Avenue to buy the latest American comics.

Looking back, and thinking of my own children’s

upbringing in Shepperton, I realise that I had a lot to take in

and digest. Every drive through Shanghai, sitting with the

White Russian nanny Vera (supposedly to guard against a

kidnap attempt by the chauffeur, though how much of her body this touchy young woman would have laid down for

me I can’t imagine), I would see something strange and

mysterious, but treat it as normal. I think this was the only

way in which I could view the bright but bloody kaleidoscope

that was Shanghai – the prosperous Chinese businessmen

pausing in the Bubbling Well Road to savour a thimble

of blood tapped from the neck of a vicious goose tethered to

a telephone pole; young Chinese gangsters in American suits

beating up a shopkeeper; beggars fighting over their pitches;

beautiful White Russian bar-girls smiling at passers-by (I

used to wonder what they would be like as my nanny, compared

with the morose Vera, who kept a sullen grip on my

overactive mind).

Nevertheless, Shanghai struck me as a magical place, a

self-generating fantasy that left my own little mind far

behind. There was always something odd and incongruous

to see: a vast firework display celebrating a new nightclub

while armoured cars of the Shanghai police drove into a

screaming mob of rioting factory workers; the army of

prostitutes in fur coats outside the Park Hotel, ‘waiting for

friends’ as Vera told me. Open sewers fed into the stinking

Whangpoo river, and the whole city reeked of dirt, disease

and a miasma of cooking fat from the thousands of Chinese

food vendors. In the French Concession the huge trams

clanked at speed through the crowds, their bells tolling.

Anything was possible, and everything could be bought and

sold. In many ways, it seems like a stage set, but at the time

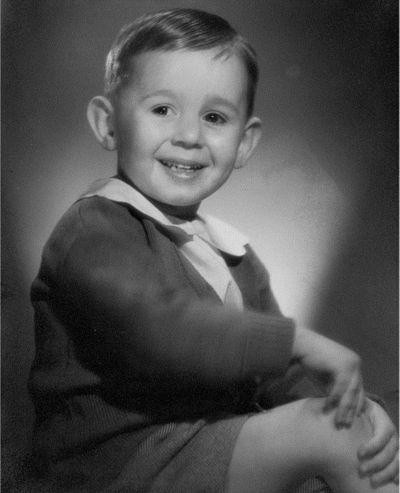

Myself in Shanghai in 1934

.

it was real, and I think a large part of my fiction has been an

attempt to evoke it by means other than memory.

At the same time there was a strictly formal side to

Shanghai life – wedding receptions at the French Club, where I was a page and first tasted cheese canapés, so disgusting

that I thought I had caught a terrible new disease.

There were race meetings at the Shanghai Racecourse, for

which everyone dressed up, and various patriotic gatherings

at the British Embassy on the Bund, ultra-formal occasions

that involved hours of waiting and nearly drove me mad. My

parents held elaborately formal dinner parties, where all the

guests were probably drunk and which usually ended for

me when some cheerful colleague of my father’s found me

hiding behind a sofa, feasting on conversations I hadn’t a

hope of grasping. ‘Edna, there’s a stowaway on board…’

My mother told me of one reception in the early 1930s

when I was introduced to Madame Sun Yat-sen, widow of

the man who overthrew the Manchus and became China’s

first president. But I think my parents probably preferred her

sister, Madame Chiang Kai-shek, close friend of America and

American big business. My mother was then a pretty young

woman in her thirties, and a popular figure at the Country

Club. She was once voted the best-dressed woman in

Shanghai, but I’m not sure if she took that as a compliment,

or whether she really enjoyed her years in Shanghai (roughly

1930 to 1948). Years later, in her sixties, she became a veteran

long-haul air traveller, and visited Singapore, Bali and Hong

Kong, but not Shanghai. ‘It’s an industrial city,’ she

explained, as if that closed the matter.

I suspect that my father, with his passion for H.G. Wells

and his belief in modern science as mankind’s saviour, enjoyed Shanghai far more. He was always telling the

chauffeur to slow down when we passed significant local

landmarks – the Radium Institute, where cancer would be

cured; the vast Hardoon estate in the centre of the International

Settlement, created by an Iraqi property tycoon

who was told by a fortune-teller that if he ever stopped

building he would die, and who then went on constructing

elaborate pavilions all over Shanghai, many of them structures

with no doors or interiors. In the confusion of traffic

on the Bund he pointed out ‘Two-Gun’ Cohen, the then

famous bodyguard of Chinese warlords, and I gazed with all

a small boy’s awe at a large American car with armed men

standing on the running-boards, Chicago-style. Before the

war my father often took me across the Whangpoo river to

his company’s factory on the eastern bank – I remember still

the fearsome noise of the spinning and weaving sheds, the

hundreds of massive Lancashire looms each watched by a

teenage Chinese girl, ready to stop her machine if a single

thread was broken. These peasant girls had long been deafened

by the din, but they were their families’ only support,

and my father opened a school next to the mill where the

illiterate girls could learn to read and write and have some

hope of becoming office clerks.