Miss Clare Remembers and Emily Davis (44 page)

Read Miss Clare Remembers and Emily Davis Online

Authors: Miss Read

He lowered the paper to the counter, folded it carefully, and adjusted his coffee machine. His eyes strayed to the window. On the sidewalk the citizens of New York struggled against vicious wind and rain. In the shining road the traffic edged its way along, the windscreen wipers nicking impatiently.

But George saw nothing of the scene. He was back in time, back in Caxley, back in the Post Office living room at Fairacre, where his trip to the States had first begun, so long ago.

When George Lamb left Fairacre School at the age of fifteen, the Second World War had been over for almost two years.

Times were hard. Rationing of food was still in existence, and the basic necessities of life, houses, work, transport and even clothes were all in short supply.

Old Mrs Lamb still ruled at Fairacre Post Office, assisted by her older son. George, it was decided, should try for work at Septimus Howard's new restaurant in Caxley market-place. With any luck, he might be taught the bakery business too. There was a double chance there to learn two trades. One, or both, could provide George Lamb with a livelihood.

The boy cycled daily to work in all weathers, and thrived on it. At that time, Septimus Howard, respected tradesman and chapel-goer, was an old man, and within a year or two of his death. Mrs Lamb had a great regard for him, and was proud to think that George was in his care. Many a time she had listened to Sep's preaching, for she was a staunch chapel-goer herself, and Sep, as a lay-preacher often came to the tiny chapel at Fairacre to give an address.

'If you do as Mr Howard tells you, and follow his example,' she told young George, 'you won't go far wrong.'

She had been widowed whilst George was still a small boy, and sound instinct told her that a man of Sep's worth could be of untold value to the boy in his impressionable years. He certainly influenced George's thinking, and gave him an insight too, into the way of running an honest business.

It was Sep's idea that George should learn the bakery business first, and he began in the usual humble way of watching methods, weighing ingredients, checking the heat of the ovens, and so on, before proceeding to mixing and making himself. He was a conscientious lad, and Sep, always gentle with young people, took extra pains with the promising boy.

As time went on, he became skilled at decorating both iced cakes for the baker's shop and the enormous rich gateaux for which the restaurant was becoming famous.

He had his midday meal in the kitchen at the rear of the restaurant, with its view of the peaceful Cax through the window. This substantial meal was a great help to Mrs Lamb whilst food was still hard to come by. In the evening the boy ate bread and cheese, washed down with a mug of cocoa, with the rest of the family.

There were still contingents of United States troops stationed in the Caxley area. Howard's Restaurant was a favourite rendezvous for the men, and young George became friendly with several of them. One in particular, a blond young giant with a crew-cut, was a frequent visitor, and he and George struck up a friendship.

He was the son of a restaurant owner in New York. His father, so George gathered, was another Septimus Howard, hard-working, teetotal, and a stalwart of the local chapel. His son was inclined to be apologetic about his father's somewhat rigid views but it was plain to George that Wilbur was secretly very proud of the old man and of his business ability.

You want to come and see the place for yourself sometime,' said Wilbur.

'No hope of that,' responded George. 'No money for one thing. And I've got a lot to learn here yet.'

'My old man expects me to go into the business.'

'Well, you will, won't you? Lucky to have something waiting for you.'

Wilbur looked thoughtful.

'I guess I don't take to the idea, somehow. Been brought up among pies and cookies all my life. I kind of want a change.'

'Such as?'

'Well, now you're going to laugh. I've a girl back home who works in a dress shop. I reckon the two of us could run a shop like that pretty good.'

'Have you got enough to set up a shop?'

'Nope. That's the snag. But if my old man could put up the cash, we'd make a go of it, never fear. It's just that he's looking to me to take over some of his jobs when I get home. It'll take a bit of breaking to him.'

'And you want me to take your place?' queried George jokingly.

'Well now, who knows? You keep it in mind, George. You might do a lot worse than try your luck in the States. Plenty of scope there for a chap like you.'

George did not give much thought to the conversation. His present mode of life was full enough, and besides he doubted if his mother would, approve of a son going so far away.

Mrs Lamb was a strongly possessive woman, and hard times had made her calculating as well. With the wages of both John and George she managed fairly easily. She had an eye for a bargain, went shopping regularly in Caxley market on Thursday afternoons, and took advantage of every cheap line offered by the shops. The thought of losing either son's contribution to the housekeeping was a nightmare to her, although she was better off than many of her neighbours.

At that time, John was courting a local girl, and having considerable trouble with his mother on that account.

'I've nothing against her,' said Mrs Lamb, mendaciously.

'Except her being in existence at all,' thought John privately, but keeping quiet for the sake of peace.

'But can you afford to get married? Where are you going to live? She's welcome here, but I don't suppose this place is good enough for her.'

'It's not that, motherâ'

'I'm quite prepared to take second place, hard though it is. I haven't had an easy time, as well you know. Bringing up two

boys all alone, with mighty little money, is no joke. Not that one expects any thanks. Young people are all the sameâtake all, give nothing.'

This sort of talk nearly drove John Lamb mad at times. He saw quite clearly that self-martyrdom pleased his cantankerous old mother. He also saw the cunning behind it. As long as she could stave off the marriage, the better off financially she would be.

Things came to a head when his girl delivered an ultimatum. Her younger sister became engaged, and their wedding day was already fixed. This galvanised the older one into action. It was unthinkable that young Mary should steal a march on her!

'Well, do you or don't you?' demanded John's fiancee. 'If we have to live here for a bit, I don't mind putting up with your mum as long as we know we're getting a house of our own, in a few months, say. But if you can't leave your mother, then say so.'

'Don't talk like that,' pleaded poor John, seeing himself between the devil and the deep sea.

'I'm fed up with waiting. If you don't want me, there's another man who does. He's asked me often enough.'

'Who's that?' said John, turning red with fury.

'I'm not saying,' replied the girl, a trifle smugly. As it happened, John Lamb never did discover who the fellow was. Could he be mythical? John often wondered later on.

But the upshot was that John's wedding was arranged very quickly, and a double celebration took place in Caxley that autumn, much to the delight of the brides' father whose pocket benefited from 'killing two birds with one stone,' as he put it bluntly. As the poor fellow had four more daughters to see launched, one could sympathise with his jubilation.

The atmosphere in the Lamb household, between the time of the girl's ultimatum and the wedding, was unbearable. Old Mrs Lamb went about her Post Office duties with a long face, and had the greatest pleasure in confiding her doubts and fears to all her customers. Most of their sympathy went towards John and his wife-to-be.

'Miserable old devil!' was the general comment. 'I wouldn't be in that girl's shoes for a pension! If John Lamb's got any sense he'll clear out and let his old mum get on with it.'

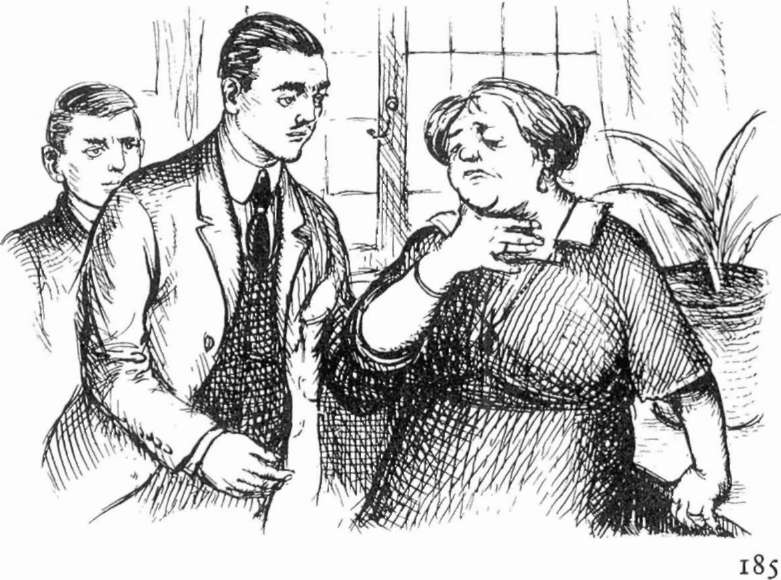

It was at this unhappy stage that George began to think seriously of Wilbur's suggestion. He began to dread his return home, as he cycled back from Caxley each evening. Sometimes a brooding silence hung over the kitchen. Sometimes his mother was in full spateâa stream of self-pity flowing from her vigorously.

'How I shall manage I just don't know,' she complained one evening. 'It's bad enough keeping three of us going with what little comes in. When there's a fourth to feed, it'll come mighty hard.'

George's pent-up patience burst.

'Maybe there'll be only three after John gets married. I'm thinking of leaving Howard's.'

There was a shocked silence.

'Leaving Howard's?' shrieked his mother. 'What's this nonsense?'

'I'd like to go to the States. Got an opening there.'

This was not strictly true, but George was enjoying his mother's discomfiture.

'You'll do no such thing,' declared Mrs Lamb, recovering her usual matriarchal powers. 'You've got a good job with Mr Howard, and you're a fool to think of throwing it up.'

'I could do the same work in New York and get twice the money. Besides I want to see places. I don't want to stick in Fairacre all my life. If I don't go now, when I'm free, I'll never go. I'll be like old John here, married and stuck here for life.'

'And what's wrong with that?' demanded his mother. She looked at her younger son's rebellious face, and changed her tactics.

'And doesn't your poor mother mean anything to you?' she began, summoning ready tears. 'The sacrifices I've made, for you two boys, nobody knows. I've skimped and saved to feed and clothe you, and what do I get? Not a ha'p'orth of gratitude!'

She mopped her eyes.

'I only hope,' she went on, raising her eyes piously towards the ceiling, 'that you two never find

yourselves

unwanted by your family. A widow's lot is hard enough without her own flesh and blood turning against her!'

'Now, mother, pleaseâ' began soft-hearted John, who could always be moved by tears.

But George was made of tougher stuff.

'Any children of mine will have a chance to do as they want in life,' he told his mother stoutly. 'What's the sense in keeping them against their will? We all have to leave home sometime. I'm thinking about it now. That's all.'

'And what about the money?' said Mrs Lamb viciously.

George looked at her steadily.

'Let's face it, ma! That's all you're worried about.'

His mother turned away pettishly, but not before George saw that his shaft had struck home. He followed up his advantage.

'I'll get better opportunities in America. After a bit, when I've got settled, I'll probably be able to send you a darn sight more each month than I give you now in a year.'

An avaricious gleam brightened his mother's eye. Nevertheless, she clung to her martyrdom.

'And how do we manage until you make your fortune?' she asked nastily.

'As other mothers do,' said George. 'I'm going to talk to Mr Howard. He'll understand how I feel. I shan't let him down, but I intend to go before long.'

Knowing herself beaten, Mrs Lamb rose to her feet, reeling very dramatically.

'I shall have to go and lie down. All this trouble's made my heart bad again.'

John took his mother's arm and helped her upstairs in silence.

Sitting below, at the kitchen table, George heard the bed springs creak under his mother's eleven stone.

John returned, looking anxious.

'D'you mean it?' he asked. 'Or are you playing up our mum?'

'I mean it all right,' replied George grimly.

As luck would have it, he came across "Wilbur next day, and told him how things stood. Would he mind asking his father what the chances were for a young man in the trade?

Wilbur threw himself into George's plans with a wholehearted zest which gave the boy encouragement when it was most needed. He was now quite determined to leave home. He would stay until John's marriage, but as soon as that was over he hoped to get away.

He did not intend to approach Sep Howard until he had heard from Wilbur's father. If he was discouraging he might just as well stay a little longer with Howard's, finding lodgings in Caxley. Whatever happened, he was not going to stop at home.

For one thing there would be little room for him when John married. For another thing, he foresaw that there would be trouble between the two women, and he was going to steer clear of that catastrophe.

But for all his determination, George suffered spells of doubt, particularly at night.

Lying sleepless in his narrow bed, he watched the fir tree outside the window, as he had done since he was a little boy. The stars behind it seemed to be caught in its dark branches, as it swayed gently, and reminded him of the Christmas tree, sparkling with tinsel, which he and John dressed every year. He would miss Fairacre, and his home. There would be no sparrows chirruping under the thatch, close to his bed-head, in New York. There would be no scent of fresh earth, or the honking of the white swans as they flew to the waters of the Cax.

And was he treating his mother roughly? In the brave light of day, he knew that he was not guilty. At night, he became the prey of doubts.