Miss Peregrine's Home For Peculiar Children (20 page)

Read Miss Peregrine's Home For Peculiar Children Online

Authors: Ransom Riggs

Tags: #Mystery, #Fantasy, #Young Adult, #Paranormal, #Horror, #Thriller

After a decadent lunch of goose sandwiches and chocolate pudding, Emma began to agitate for the older kids to go swimming. “Out of the question,” Millard groaned, the top button of his pants popping open. “I’m stuffed like a Christmas turkey.” We were sprawled on velvet chairs around the sitting room, full to bursting. Bronwyn lay curled with her head between two pillows. “I’d sink straight to the bottom,” came her muffled reply.

But Emma persisted. After ten minutes of wheedling she’d roused Hugh, Fiona, and Horace from their naps and challenged Bronwyn, who apparently could not forgo a competition of any kind, to a swimming race. Upon seeing us all trooping out of the house, Millard scolded us for trying to leave him behind.

The best spot for swimming was by the harbor, but getting there meant walking straight through town. “What about those crazy drunks who think I’m a German spy?” I said. “I don’t feel like getting chased with clubs today.”

“You twit,” Emma said. “That was

yesterday

. They won’t remember a thing.”

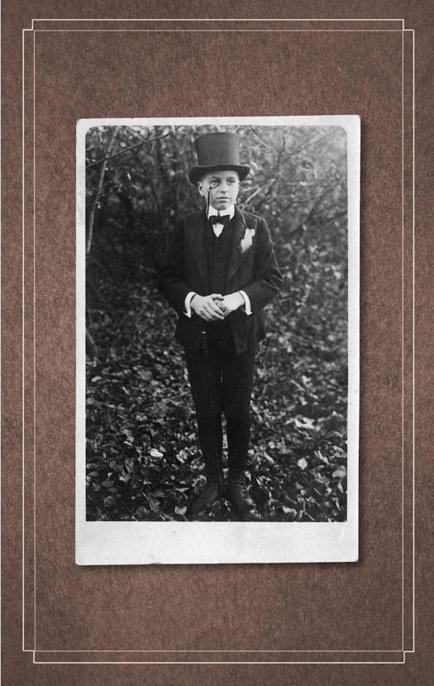

“Just hang a towel ’round you so they don’t see your, er, future clothes,” said Horace. I had on jeans and a T-shirt, my usual outfit, and Horace wore his customary black suit. He seemed to be of the Miss Peregrine school of dress: morbidly ultraformal, no matter the occasion. His photograph was among those I’d found in the smashed trunk, and in an attempt to “dress up” for it he’d gone completely overboard: top hat, cane, monocle—the works.

“You’re right,” I said, cocking an eyebrow at Horace. “I wouldn’t want anyone to think I was dressed weird.”

“If it’s my waistcoat you’re referring to,” he replied haughtily, “yes, I admit I am a follower of fashion.” The others snickered. “Go ahead, have a laugh at old Horace’s expense! Call me a dandy if you will, but just because the villagers won’t remember what you wear doesn’t give you license to dress like a vagabond!” And with that he set about straightening his lapels, which only made the kids laugh harder. In a snit, he pointed an accusing finger at my clothes. “As for him, God help us if

that’s

all our wardrobes have to look forward to!”

When the laughter had died down, I pulled Emma aside and whispered, “What exactly is it that makes Horace peculiar—aside from his clothes, I mean?”

“He has prophetic dreams. Gets these great nightmares every so often, which have a disturbing tendency to come true.”

“How often? A lot?”

“Ask him yourself.”

But Horace was in no mood to entertain my questions. So I filed it away for another time.

As we came into town I wrapped a towel around my waist and hung another from my shoulders. Though it wasn’t exactly prophecy, Horace was right about one thing: nobody recognized me. Walking down the main path we got a few odd looks, but no one bothered us. We even passed the fat man who’d made such a stink over me in the bar. He was stuffing a pipe outside the tobacconist’s shop and blathering on about politics to a woman who was barely listening. I couldn’t help staring at him as we passed. He stared back, without even a flicker of recognition.

It was like someone had hit “reset” on the whole town. I kept noticing things I’d seen the day before: the same wagon rushing wildly down the path, its back wheel fishtailing in the gravel; the same women lining up outside the well; a man tarring the bottom of a rowboat, no further along in his task than he’d been twenty-four hours ago. I almost expected to see my doppelgänger sprinting across town pursued by a mob, but I guess things didn’t work that way.

“You guys must know a lot about what goes on around here,” I said. “Like yesterday, with the planes and that cart.”

“It’s Millard who knows everything,” said Hugh.

“It’s true,” said Millard. “In fact, I am in the midst of compiling the world’s first complete account of one day in the life of a town, as experienced by everyone in it. Every action, every conversation, every sound made by each of the one hundred fifty-nine human and three hundred thirty-two animal residents of Cairnholm, minute by minute, sunup to sundown.”

“That’s incredible,” I said.

“I can’t help but agree,” he replied. “In just twenty-seven years I’ve already observed half the animals and nearly all the humans.”

My mouth fell open. “Twenty-seven

years

?”

“He spent three years on pigs alone!” Hugh said. “That’s all day every day for three years taking notes on

pigs!

Can you imagine? ‘This one dropped a load of arse biscuits!’ ‘That one said

oink-oink

and then went to sleep in its own filth!’ ”

“Notes are absolutely essential to the process,” Millard explained patiently. “But I can understand your jealousy, Hugh. It promises to be a work unprecedented in the history of academic scholarship.”

“Oh, don’t cock your nose,” Emma said. “It’ll also be unprecedented in the history of dull things. It’ll be the dullest thing ever written!”

Rather than responding, Millard began pointing things out just before they happened. “Mrs. Higgins is about to have a coughing fit,” he’d say, and then a woman in the street would cough and hack until she was red in the face, or “Presently, a fisherman will lament the difficulty of plying his trade during wartime,” and then a man leaning on a cart filled with nets would turn to another man and say, “There’s so many damned U-boats in the water now it ain’t even safe for a bloke to go tickle his own lines!”

I was duly impressed, and told him so. “I’m glad

someone

appreciates my work,” he replied.

We walked along the bustling harbor until the docks ran out and then followed the rocky shore toward the headlands to a sandy cove. We boys stripped down to our underwear (all except Horace, who would remove only his shoes and tie) while the girls disappeared to change into modest, old-school bathing suits. Then we all swam. Bronwyn and Emma raced each other while the rest of us paddled around; once we’d exhausted ourselves, we climbed onto the sand and napped. When the sun was too hot we fell back into the water, and when the chilly sea made us shiver we crawled out again, and so it went until our shadows began to lengthen across the cove.

We got to talking. They had a million questions for me, and, far away from Miss Peregrine, I could answer them frankly. What was my world like? What did people eat, drink, wear? When would sickness and death be overcome by science? They lived in splendor but were starving for new faces and new stories. I told them whatever I could, racking my brain for nuggets of twentieth-century history from Mrs. Johnston’s class—the moon landing! the Berlin Wall! Vietnam!—but they were hardly comprehensive.

It was my time’s technology and standard of living that amazed them most. Our houses were air-conditioned. They’d heard of televisions but had never seen one and were shocked to learn that my family had a talking-picture box in almost every room. Air travel was as common and affordable to us as train travel was to them. Our army fought with remote-controlled drones. We carried telephone-computers that fit in our pockets, and even though mine didn’t work here (nothing electronic seemed to), I pulled it out just to show them its sleek, mirrored enclosure.

It was edging toward sunset when we finally started back. Emma stuck to me like glue, the back of her hand brushing mine as we walked. Passing an apple tree on the outskirts of town, she stopped to pick one, but even on tiptoes the lowest fruit was out of reach, so I did what any gentleman would do and gave her a boost, wrapping my arms around her waist and trying not to groan as I lifted, her white arm outstretched, wet hair glinting in the sun. When I let her down she gave me a little kiss on the cheek and handed me the apple.

“Here,” she said, “you earned it.”

“The apple or the kiss?”

She laughed and ran off to catch up with the others. I didn’t know what to call it, what was happening between us, but I liked it. It felt silly and fragile and good. I put the apple in my pocket and ran after her.

When we came to the bog and I said I had to go home, she pretended to pout. “At least let me escort you,” she said, so we waved goodbye to the others and crossed over to the cairn, me doing my best to memorize the placement of her feet as we went.

When we got there I said, “Come with me to the other side a minute.”

“I shouldn’t. I’ve got to get back or the Bird will suspect us.”

“Suspect us of what?”

She smiled coyly. “Of ... something.”

“Something.”

“She’s always on the lookout for something,” she said, laughing.

I changed tactics. “Then why don’t you come see me tomorrow instead?”

“See you? Over there?”

“Why not? Miss Peregrine won’t be around to watch us. You could even meet my dad. We won’t tell him who you are, obviously. And then maybe he’ll ease up a little about where I’m going and what I’m doing all the time. Me hanging out with a hot girl? That’s like his fondest dad-dream wish.”

I thought she might smile at the hot girl thing, but instead she turned serious. “The Bird only allows us to go over for a few minutes at a time, just to keep the loop open, you know.”

“So tell her that’s what you’re doing!”

She sighed. “I want to. I do. But it’s a bad idea.”

“She’s got you on a pretty short leash.”

“You don’t know what you’re talking about,” she said with a scowl. “And thanks for comparing me to a dog. That was brilliant.”

I wondered how we’d gone from flirting to fighting so quickly. “I didn’t mean it like that.”

“It’s not that I wouldn’t like to,” she said. “I just can’t.”

“Okay, I’ll make you a deal. Forget coming for the whole day. Just come over for a minute, right now.”

“One minute? What can we do in one minute?”

I grinned. “You’d be surprised.”

“Tell me!” she said, pushing me.

“Take your picture.”

Her smile disappeared. “I’m not exactly at my most fetching,” she said doubtfully.

“No, you’re great. Really.”

“Just one minute? Promise?”

I let her go into the cairn first. When we came out again the world was misty and cold, though thankfully the rain had stopped. I pulled out my phone and was happy to see that my theory was right. On this side of the loop, electronic things worked fine.

“Where’s your camera?” she said, shivering. “Let’s get this over with!”

I held up the phone and took her picture. She just shook her head, as if nothing about my bizarre world could surprise her anymore. Then she dodged away, and I had to chase her around the cairn, both of us laughing, Emma ducking out of view only to pop up again and vamp for the camera. A minute later I’d taken so many pictures that my phone had nearly run out of memory.

Emma ran to the mouth of the cairn and blew me an air-kiss. “See you tomorrow, future boy!”

I lifted my hand to wave goodbye, and she ducked into the stone tunnel.

* * *

I skipped back to town freezing and wet and grinning like an idiot. I was still blocks away from the pub when I heard a strange sound rising above the hum of generators—someone calling my name. Following the voice, I found my father standing in the street in a soggy sweater, breath pluming before him like muffler exhaust on a cold morning.

“Jacob! I’ve been looking for you!”

“You said be back by dinner, so here I am!”

“Forget dinner. Come with me.”

My father never skipped dinner. Something was most definitely amiss.

“What’s going on?”

“I’ll explain on the way,” he said, marching me toward the pub. Then he got a good look at me. “You’re all wet!” he exclaimed. “For God’s sake, did you lose your

other

jacket, too?”

“I, uh ...”

“And why is your face red? You look sunburned.”

Crap. A whole afternoon at the beach without sunblock. “I’m all hot from running,” I said, though the skin on my arms was pimpled from cold. “What’s happening? Did someone die, or what?”

“No, no, no,” he said. “Well, sort of. Some sheep.”

“What’s that got to do with us?”

“They think it was kids who did it. Like a vandalism thing.”

“They who? The sheep police?”

“The farmers,” he said. “They’ve interrogated everyone under the age of twenty. Naturally, they’re pretty interested in where you’ve been all day.”

My stomach sank. I didn’t exactly have a watertight cover story, and I raced to think of one as we approached the Priest Hole.

Outside the pub, a small crowd was gathered around a quorum of very pissed-off-looking sheep farmers. One wore muddy coveralls and leaned threateningly on a pitchfork. Another had Worm by the collar. Worm was dressed in neon track pants and a shirt that read

I

LOVE IT WHEN THEY CALL ME BIG POPPA

. He’d been crying, snot bubbling on his upper lip.

A third farmer, rail-thin and wearing a knit cap, pointed at me as we approached. “Here he is!” he called out. “Where you been off to, son?”

Dad patted me on the back. “Tell them,” he said confidently.

I tried to sound like I had nothing to hide. “I was exploring the other side of the island. The big house.”

Knit Cap looked confused. “Which big house?”