Miss Peregrine's Home For Peculiar Children (30 page)

Read Miss Peregrine's Home For Peculiar Children Online

Authors: Ransom Riggs

Tags: #Mystery, #Fantasy, #Young Adult, #Paranormal, #Horror, #Thriller

Gradually the heart in Enoch’s hand began to slow and shrink, its color fading to a blackish gray, like meat left too long in the freezer. Enoch threw it on the ground and thrust his empty hand at me. I pulled out the heart I’d been keeping in my pocket and gave it to him. He repeated the same process, the heart pumping and sputtering for a while before faltering like the last one. Then he did it a third time, using the heart he’d given to Emma.

Bronwyn’s heart was the only one left—Enoch’s last chance. His face took on a new intensity as he raised it above Martin’s rude coffin, squeezing it like he meant to drive his fingers through. As the heart began to shake and tremble like an overcranked motor, Enoch shouted, “Rise up, dead man. Rise up!”

I saw a flicker of movement. Something had shifted beneath the ice. I leaned as close as I could stand to, watching for any sign of life. For a long moment there was nothing, but then the body wrenched as suddenly and forcefully as if it had been shocked with a thousand volts. Emma screamed, and we all jumped back. When I lowered my arms to look again, Martin’s head had turned in my direction, one cataracted eye wheeling crazily before fixing, it seemed, on me.

“He sees you!” Enoch cried.

I leaned in. The dead man smelled of turned earth and brine and something worse. Ice fell away from his hand, which rose up to tremble in the air for a moment, afflicted and blue, before coming to rest on my arm. I fought the urge to throw it off.

His lips fell apart and his jaw hinged open. I bent down to hear him, but there was nothing to hear.

Of course there isn’t

, I thought,

his lungs have burst

—but then a tiny sound leaked out, and I leaned closer, my ear almost to his freezing lips. I thought, strangely, of the rain gutter by my house, where if you put your head to the bars and wait for a break in traffic, you can just make out the whisper of an underground stream, buried when the town was first built but still flowing, imprisoned in a world a permanent night.

The others crowded around, but I was the only one who could hear the dead man. The first thing he said was my name.

“Jacob.”

Fear shot through me. “Yes.”

“I was dead.” The words came slowly, dripping like molasses. He corrected himself. “Am dead.”

“Tell me what happened,” I said. “Can you remember?”

There was a pause. The wind whistled through the gaps in the walls. He said something and I missed it.

“Say it again. Please, Martin.”

“He killed me,” the dead man whispered.

“Who.”

“My old man.”

“You mean Oggie? Your uncle?”

“My old man,” he said again. “He got big. And strong, so strong.”

“Who did, Martin?”

His eye closed, and I feared he was gone for good. I looked at Enoch. He nodded. The heart in his hand was still beating.

Martin’s eye flicked beneath its lid. He began to speak again, slowly but evenly, as if reciting something. “For a hundred generations he slept, curled like a fetus in the earth’s mysterious womb, digested by roots, fermenting in the dark, summer fruits canned and forgotten in the larder until a farmer’s spade bore him out, rough midwife to a strange harvest.”

Martin paused, his lips trembling, and in the brief silence Emma looked at me and whispered, “What’s he saying?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “But it sounds like a poem.”

He continued, his voice wavering but loud enough now that everyone could hear—”Blackly he reposes, tender face the color of soot, withered limbs like veins of coal, feet lumps of driftwood hung with shriveled grapes”—and finally I recognized the poem. It was the one he’d written about the bog boy.

“Oh Jacob, I took such good careful care of him!” he said. “Dusted the glass and changed the soil and made him a home—like my own big bruised baby. I took such careful care, but—” He began to shake, and a tear ran down his cheek and froze there. “But he killed me.”

“Do you mean the bog boy? The Old Man?”

“Send me back,” he pleaded. “It hurts.” His cold hand kneaded my shoulder, his voice fading again.

I looked to Enoch for help. He tightened his grip on the heart and shook his head. “Quick now, mate,” he said.

Then I realized something. Though he was describing the bog boy, it wasn’t the bog boy who had killed him.

They only become visible to the rest of us when they’re eating

, Miss Peregrine had told me,

which is to say, when it’s too late

. Martin had seen a hollowgast—at night, in the rain, as it was tearing him to shreds—and had mistaken it for his most prized exhibit.

The old fear began to pump, coating my insides with heat. I turned to the others. “A hollowgast did this to him,” I said. “It’s somewhere on the island.”

“Ask him where,” said Enoch.

“Martin, where. I need to know where you saw it.”

“Please. It hurts.”

“Where did you see it?”

“He came to my door.”

“The old man did?”

His breath hitched strangely. He was hard to look at but I made myself do it, following his eye as it shifted and focused on something behind me.

“No,” he said.

“He

did.”

And then a light swept over us and a loud voice barked,

“Who’s there!”

Emma closed her hand and the flame hissed out, and we all spun to see a man standing in the doorway, holding a flashlight in one hand and a pistol in the other.

Enoch yanked his arm out of the ice while Emma and Bronwyn closed ranks around the trough to block Martin from view. “We didn’t mean to break in,” Bronwyn said. “We was just leaving, honest!”

“Stay where you are!” the man shouted. His voice was flat, accentless. I couldn’t see his face through the beam of light, but the layered jackets he wore were an instant giveaway. It was the ornithologist.

“Mister, we ain’t had nothing to eat all day,” Enoch whined, for once sounding like a twelve-year-old. “All we come for was a fish or two, swear!”

“Is that so?” said the man. “Looks like you’ve picked one out. Let’s see what kind.” He waved his flashlight back and forth as if to part us with the beam. “Step aside!”

We did, and he swept the light over Martin’s body, a landscape of garish ruin. “Goodness, that’s an odd-looking fish, isn’t it?” he said, entirely unfazed. “Must be a fresh one. He’s still moving!” The beam came to rest on Martin’s face. His eye rolled back and his lips moved soundlessly, just a reflex as the life Enoch had given him drained away.

“Who are you?” Bronwyn demanded.

“That depends on whom you ask,” the man replied, “and it isn’t nearly as important as the fact that I know who

you

are.” He pointed the flashlight at each of us and spoke as if quoting some secret dossier. “Emma Bloom, a spark, abandoned at a circus when her parents couldn’t sell her to one. Bronwyn Bruntley, berserker, taster of blood, didn’t know her own strength until the night she snapped her rotten stepfather’s neck. Enoch O’Connor, dead-riser, born to a family of undertakers who couldn’t understand why their clients kept walking away.” I saw each of them shrink away from him. Then he shone the light at me. “And Jacob. Such peculiar company you’re keeping these days.”

“How do you know my name?”

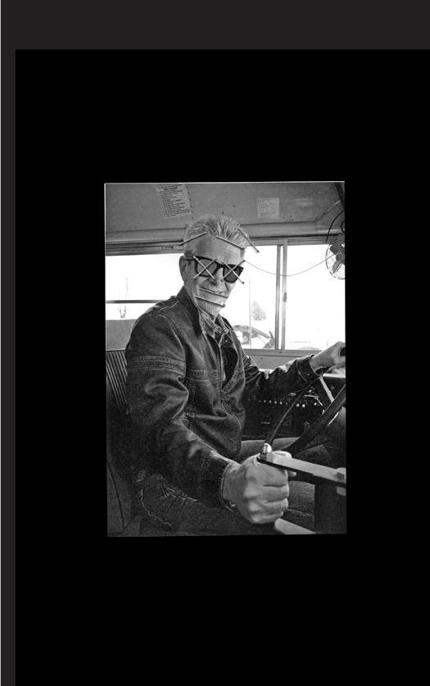

He cleared his throat, and when he spoke again his voice had changed radically. “Did you forget me so quick?” he said in a New England accent. “But then I’m just a poor old bus driver, guess you wouldn’t remember.”

It seemed impossible, but somehow this man was doing a dead-on impression of my middle school bus driver, Mr. Barron. A man so despised, so foul tempered, so robotically inflexible that on the last day of eighth grade we defaced his yearbook picture with staples and left it like an effigy behind his seat. I was just remembering what he used to say as I got off the bus every afternoon when the man before me sang it out:

“End of the line, Portman!”

“Mr. Barron?” I asked doubtfully, struggling see his face through the flashlight beam.

The man laughed and cleared his throat, his accent changing again. “Either him or the yard man,” he said in a deep Florida drawl. “Yon trees need a haircut. Give yah good price!” It was the pitch-perfect voice of the man who for years had maintained my family’s lawn and cleaned our pool.

“How are you doing that?” I said. “How do you know those people?”

“Because I

am

those people,” he said, his accent flat again. He laughed, relishing my baffled horror.

Something occurred to me. Had I ever seen Mr. Barron’s eyes? Not really. He was always wearing these giant, old-man sunglasses that wrapped around his face. The yard man wore sunglasses, too, and a wide-brimmed hat. Had I ever given either of them a hard look? How many other roles in my life had this chameleon played?

“What’s happening?” Emma said. “Who is this man?”

“Shut up!” he snapped. “You’ll get your turn.”

“You’ve been watching me,” I said. “You killed those sheep. You killed Martin.”

“Who, me?” he said innocently. “I didn’t kill anyone.”

“But you’re a wight, aren’t you?”

“That’s

their

word,” he said.

I couldn’t understand it. I hadn’t seen the yard man since my mother replaced him three years ago, and Mr. Barron had vanished from my life after eighth grade. Had they—he—really been following me?

“How’d you know where to find me?”

“Why, Jacob,” he said, his voice changing yet again, “you told me yourself. In confidence, of course.” It was a middle-American accent now, soft and educated. He tipped the flashlight up so that its glow spilled onto his face.

The beard I’d seen him wearing the other day was gone. Now there was no mistaking him.

“Dr. Golan,” I said, my voice a whisper swallowed by the drumming rain.

I thought back to our telephone conversation a few days ago. The noise in the background—he’d said he was at the airport. But he wasn’t picking up his sister. He was coming after me.

I backed against Martin’s trough, reeling, numbness spreading through me. “The neighbor,” I said. “The old man watering his lawn the night my grandfather died. That was you, too.”

He smiled.

“But your eyes,” I said.

“Contact lenses,” he replied. He popped one out with his thumb, revealing a blank orb. “Amazing what they can fabricate these days. And if I may anticipate a few more of your questions, yes, I am a licensed therapist—the minds of common people have long fascinated me—and no, despite the fact that our sessions were predicated on a lie, I don’t think they were a complete waste of time. In fact, I may be able to continue helping you—or, rather, we may be able to help each other.”

“Please, Jacob,” Emma said, “don’t listen to him.”

“Don’t worry,” I said. “I trusted him once. I won’t make that mistake again.”

Golan continued as though he hadn’t heard me. “I can offer you safety, money. I can give you your life back, Jacob. All you have to do is work with us.”

“Us?”

“Malthus and me,” he said, turning to call over his shoulder. “Come and say hello, Malthus.”

A shadow appeared in the doorway behind him, and a moment later we were overcome by a noxious wave of stench. Bronwyn gagged and fell back a step, and I saw Emma’s fists clench, as if she were thinking about charging it. I touched her arm and mouthed,

Wait

.

“This is all I’m proposing,” Golan continued, trying to sound reasonable. “Help us find more people like you. In return, you’ll have nothing to fear from Malthus or his kind. You can live at home. In your free time you’ll come with me and see the world, and we’ll pay you handsomely. We’ll tell your parents you’re my research assistant.”

“If I agree,” I said, “what happens to my friends?”

He made a dismissive gesture with his gun. “They made their choice long ago. What’s important is that there’s a grand plan in motion, Jacob, and you’ll be part of it.”

Did I consider it? I suppose I must have, if only for a moment. Dr. Golan was offering me exactly what I’d been looking for: a third option. A future that was neither

stay here forever

nor

leave and die

. But one look at my friends, their faces etched with worry, banished any temptation.

“Well?” said Golan. “What’s your answer?”

“I’d die before I did anything to help you.”

“Ah,” he said, “but you already have helped me.” He began to back toward the door. “It’s a pity we won’t have any more sessions together, Jacob. Though it isn’t a total loss, I suppose. The four of you together might be enough to finally shift old Malthus out of the debased form he’s been stuck in so long.”

“Oh, no,” Enoch whimpered, “I don’t want to be eaten!”

“Don’t cry, it’s degrading,” snapped Bronwyn. “We’ll just have to kill them, that’s all.”

“Wish I could stay and watch,” Golan said from the doorway. “I do love to watch!”

And then he was gone, and we were alone with it. I could hear the creature breathing in the dark, a viscid leaking like faulty pipeworks. We each took a step back, then another, until our shoulders met the wall, and we stood together like condemned prisoners before a firing squad.

“I need a light,” I whispered to Emma, who was in such shock that she seemed to have forgotten her own power.