Mistle Child (Undertaken Trilogy)

Read Mistle Child (Undertaken Trilogy) Online

Authors: Ari Berk

C

ONTENTS

4.

Regrets

6.

Words

10.

Highway

13.

Threshold

15.

At Table

18.

Woken

19.

Knock, Knock

20.

Relativity

22.

Lost Child

23.

Solar

24.

Garden Party

25.

Old Flame

26.

Down

27.

The Help

29.

Fallen

31.

Wake Up

32.

In the Woods

34.

Lullaby

38.

Curses

41.

Homecoming

For Tracy Ford

Amicitia Numquam Moritur

Here is the book of thy Descent . . .

Here begin the Terrors.

Here begin the Miracles.

—

Perlesvaus

, 1225

There the patient houses grow

While through the rooms the flesh must flow.

Mothers’, daughters’, fathers’, sons’,

On and on the river runs . . .

—From “A Devon Signpost” by Jacquetta Hawkes

Thus he arrived before a great castle,

on whose façade were carved the words:

I belong to no one and to all.

Before entering you were already here.

When you leave you shall remain.

—From

Jacques Le Fataliste

(1773) by Diderot

P

ROLOGUE

“B

RING HOME THE CHILD

. . . ,” she said through her sobs. “Little soul, by swift wing fly homeward to me.” Maud Umber spoke desperately, her eyes spilling over with tears. She looked as though she had been crying for a thousand years.

She could move freely at most times through the whole of the house, though she often allowed her losses to hold her here, in the zone of the tears of fire, and within her private chapel. This was her own place, a casket for her grief. Here, alone in the chapel, Maud Umber gave free rein to her sorrow.

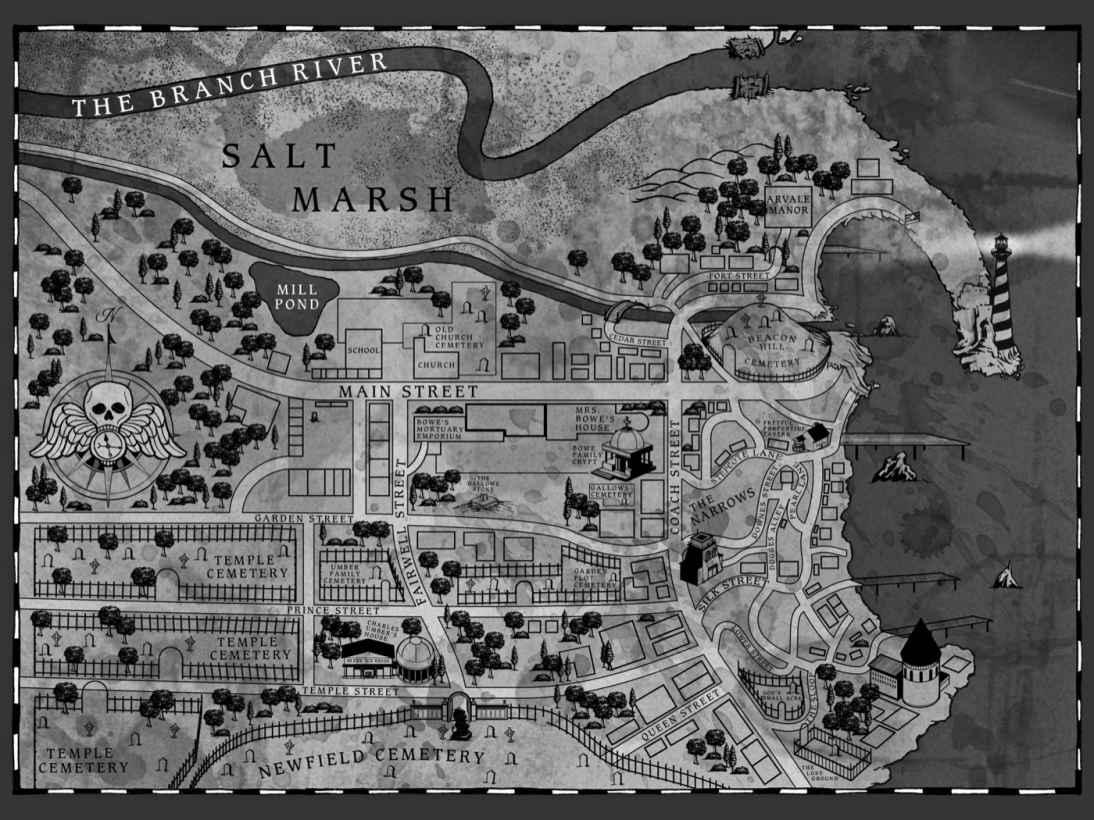

She stood in a long woolen gown, limned with flickering, melancholic fire, looking out over the twilight salt marshes. The deep casement of the window was used as an altar and was thick with wax from the centuries of candles left burning there. Little blue flames flowed and leapt across the surface of her hands and fingers as she lit another candle. She stared at a small, gilded statue of a woman who sat on a throne with a small child in her lap.

Maud closed her eyes and wrung her hands in front of her heart in desperate supplication.

“Almighty and all merciful Queen, to whom all of this world fleeth for succor, Flower of Flowers, help and relieve my mighty misery. Lady of Heaven and Mother of the Stars, Thou who guardest little children in life and in the hour of their death, and hast prepared for them,

and their mothers,

a spacious place, even in the angelic abodes brightly radiant which befit their purity, wherein the souls of the righteous dwell, Thou, Cause of Our Joy, who makest a way for all the mothers of the world: Do Thou take pity, and restore my child to me . . . to my arms. Let a mother’s prayer be answered, I beg You, Holy Mother, Advocate of Eve. Bring home the child. Please, Mother of Heaven, light the way for my child to come home again so that we may make our way to Your side. Bring home the child. BRING HOME THE CHILD. . . .”

The prayer became a scream woven with every kind of sorrow and longing and misery. It was the cry of a soul torn into portions of unfathomable grief. She screamed until there were no more screams left in her. She dropped to the floor, looking up at the carved beams of the ceiling and the thick, impervious stone of the walls.

Shadows hung all about her, cast from the candles and from the preternatural glow rising from her form. Her chest heaved as she turned to look at the fluttering tapers. Suddenly, beyond the window’s frame, something flew upward from the earth and filled the air of the distant sky. Flocks of small birds were circling over the salt marshes, joined in their flight by the night herons. Something was happening. That place was changing. She rose from the floor and walked quickly to a bronze mirror hanging next to the hearth. She breathed across its surface and whispered, “Mother of Heaven,

who

hath caused this?” An image rose.

A young man, a scion of her own house, blood-kin, stood before the salt marshes where nested the souls of the mothers of the lost. She knew that place well and had at various times looked out over the water, seeking solace with those weeping souls who had also lost their children, but whom she could never join. Now the once heavy, miserable air of the marshes was light with birdsong. Small birds. Children. The spirits of children filled the air. And below them stood a young man. It was the son of Amos Umber, and he had brought the lost children to the Bowers of the Night Herons where the mothers of loss had long been waiting to be free of their sorrows, to have their hearts restored to them, to find their children, any children, to whom they could give comfort, and so know peace.

Maud Umber’s heart leapt and the flames that traced her body stilled and nearly went out. So, the child of Amos Umber held within his hands the rare power to bring lost children home. She went to the door of the small ancient chapel, stepped across the threshold, and ascended one of the high towers of the house. Without any consideration, without a care for the consequences, she raised her arms and spoke the words of summoning.

“Let name call out to name! Scion of the house of Umber, come home! Your family calls you. Take up the mantle that is yours by rite and right. By threshold and Door Doom, by Limbus and mansion, by hall, by chamber, by lintel and post: Child of Amos Umber, come, now, by the ancient way, to the house of your kin!”