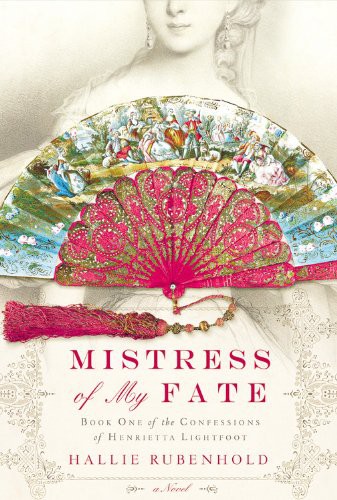

Mistress of My Fate

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

For my mother, Marsha, and the many other women in

my life who encouraged me to write fiction.

5th March 1835

My dear reader, how pleased I am that you have purchased this volume! It warms my heart that you have requested it from your bookseller; that he has wrapped it carefully in brown paper and string and handed it to you. How happy I am that you have taken it home with you to read in the quiet of your sitting room or library. Now you may know the truth, and nothing gives me greater relief than this.

I have no doubt that many of you have come to this work out of curiosity. You have heard so much about me, most of which is pure fabrication. Now that you have torn off the packaging and cut the pages, you can begin to read my story and to know who I am. You see, for some time a relation of mine has been attempting to discredit me in the most reprehensible manner. I have no doubt that he too sent a servant to his local bookseller to collect a copy of this work. As you read this, so does he. His eyes are scanning every word, searching every syllable. He is among you, taking in my story alongside you.

To him I say, Lord Dennington, do not think I have written these memoirs because of you. Do not flatter yourself. You are only part of the reason. There is much I need to say on the matter of my life and I have grown weary of your slander. Whomever you have hired to do your disgraceful deeds, whether it is those shameless scribes who will print anything for a crust of bread, or that unscrupulous little spy you

planted among my loyal staff, they are not capable of telling the truth. You pay them and so they will say anything. Certainly, a man who has seen as much of the world as you should know this.

Now it is my turn to pick up my pen, to clear my name, to scrub away the lies with which you have stained it. I must commend you for the amusement you have provided for me and my friends. We laughed heartily at your accusations—that I had been a circus performer, that I worked as a charlatan attempting to revive the dead and, worse still, that I murdered a ship of sailors. Really, this is quite absurd.

No, sir, as you will come to realize, these memoirs are not written solely because of you. I write because it is time for the public to hear my story, because for as long as I have been called Mrs. Lightfoot, great men and women have asked for it. The world wants my confession yet, until this moment, I refused to honour that request. I wished to keep my life and my adventures quiet. Like you, my lord, discretion was one of the virtues I was taught as a child.

As for my other readers, whose sensibilities I wish to protect, I feel the need to issue a warning. In these pages I set out to tell the absolute truth. If you take offence easily, if you are faint of heart or of a delicate nature, there is much here that you are likely to find objectionable. It is necessary for you to understand why I have, in the past, refused to discuss these private matters. My story is not an easy one to relay, nor is it likely to be short.

I shall begin by telling you what I remember most vividly: an early morning in late October. I was but seventeen and so unprepared for the world that I hardly knew how to dress myself, let alone judge character or transact the business of ordinary life. I sat on the floor of my bedchamber in the darkness, entirely unaware of the hour. There was no fire in my grate, nor would there be anyone coming to light it. I shivered, from both the cold and a complete terror of that which I knew I must do.

For most of the night I had sobbed. I had lain outstretched on the

floor, like a condemned prisoner, unable to move or think, able only to ache. My life as I had known it was now about to end. But, as any good Christian will tell you, with death there also comes resurrection and the possibility of a better existence elsewhere. I knew this in my heart, and that rebirth was the sole path open to me. I had only to muster the courage to grab for it and, in doing so, let go of all that tied me tothe girl I had been.

So I did this, while the moon threw its dim cast across my window sill. I worked without so much as a candle to guide me, rummaging through the most essential of my belongings: linens, stockings, skirts, a petticoat and, most importantly, the few small items of value that I as a young lady owned. Of all a woman’s possessions, jewels will get her the furthest and mine, on several occasions, have saved me from experiencing the grossest of depredations. At the time, I had but two trinkets: a gold and pearl cross, which I always wore upon my person; and a pair of simple pearl eardrops. I was too young for diamonds. Those are for married women, and in any case, owing to my precarious position within their family, Lord and Lady Stavourley saw no need to adorn me so lavishly.

I wrapped my bundle as a servant would, in a sheet. I had never before carried my own belongings and I did not even know how to tie them up securely. However, I found that soft packet offered me some comfort as I clutched it to my breast. It calmed my trembling.

I dressed for the road, but not without some struggle, sliding on my sturdiest shoes and fumbling with the buttons of my grey riding habit. Around my shoulders I threw my blue cape, the hood of which rested atop my black hat. I hoped to look respectable for my journey without drawing attention to myself. In truth, I knew that most people would be able to guess my circumstances. It is not usual to see a well-dressed young lady with spotless white gloves and a quivering expression travelling unchaperoned.

It was not until after I had attired myself and gathered my belongings

that my mind, like a lamp, flickered out. My lungs and heart and legs took over. My breathing was so harsh that I feared all of Melmouth could hear my gasps as I carefully navigated the treacherous steps of the back stairs. The chill within the stony walls turned my breath to steam. I was like an animal, clambering through the darkness. I stole through the narrow corridor near the kitchens, passing by the doors of servants, still sunk deeply into their warm straw mattresses. In an hour, the first light of morning would wake them and, with so many pairs of eyes on guard, my flight would have been impossible. You must understand that, by then, they hated me. They would have set upon me like a pack of slavering dogs.

Aware of this, I picked my way carefully along the row of doors. To my ear, the gentle clack of my heels reverberated like cannon fire. How I wished to bolt when I saw that window above the entryway, illuminating the porthole to my release! Instead, I continued to creep nearer and nearer, until my hands rested on the entry door. At last, with a firm push, I passed out of one life and into the next.

I can understand why infants scream when they come into our world. The strain of birth is enormous. The cold that greets them foretells what awaits them in life. It is as if they know from their very first breath that the warmth of the womb and all of its comforts have been lost for ever.

When I stepped over the threshold of Melmouth House and into the sprawl of parkland, I bawled as if my heart would break. The sobs came with such force that I feared they would echo through the park and wake the entire household. I had to stop my mouth with my fist. As I ran, scrambling, tripping across the frost-crusted grass, I howled, unable to contain my anguish. I have never known such heart-tearing pain as I did that morning, when I cut the cord that held me to my only true parent.

My legs knew where they carried me: to the perimeter wall. I would not risk passing the gatehouses, or scaling the heights to my freedom.

There was one break, filled in loosely with stones, where an old door had been. Poachers were known to slip through it, their sacks dripping with Lord Stavourley’s grouse and rabbits. I had seen the spot several months earlier, but finding it in the dark was to prove difficult.

I tumbled through the park, startling sleepy deer, dislodging bats and rousing a variety of creatures that squealed and scampered off at my approach. I tore through the copse with an urgency that they alone might have understood. Although I knew every path and trail, every pool and corner of Melmouth, I was not so familiar with it while it lay beneath the curtain of night. With my eyes ablaze with tears, I travelled in a state of near blindness, sinking in mud to my shins, my cape hemmed with filth and fallen leaves, my stockings already sodden and stained beyond laundering. It took some scrambling for me to find the precise point in the wall. By then the sky was softening into the deep blue of dawn. I pushed and kicked with all my might. Eventually, three of the stones fell away and I was able to squeeze myself, mouse-like, through the opening.

I emerged upon the road to Norwich and stood there, blinking into the stillness. I had no way of knowing which direction I should turn. I cannot say whether it was fortune or instinct that led me, but the route I chose was the correct one. Although I had given up running, my pace remained steady and brisk. My heart continued to thump like a battalion’s drummer. It was nearly three miles to the White Hart Inn, where the mail coach called. I had not an inkling when it arrived, but knew I had to try my luck.

Ah, was that a sigh of relief I heard from you? You think I have made a successful escape? Let me remind you, my friends, before you become certain that the worst was behind me, that any obstacle might have thwarted my progress. I might have been discovered by the steward or his men; I might have met with an accident. By mid-morning my absence would have been discovered and the entire house would have been thrown into turmoil. I realize now that I must have caused

Lord Stavourley a great deal of anguish. The images that entered his mind would have been dreadful. I am certain he thought I had taken my own life, that his men were likely to find me at the bottom of the lake or hanging from a tree in the park. For this, I am truly sorry.

The possibility that I would be found out and marched back to Melmouth was ever-present. I had no idea what I might find on my arrival at the inn, or how long I might have to wait for my transportation. I knew only that the longer I remained in one place, the more likely I was to be found. Until I boarded the coach, there would also be the possibility I would lose my nerve. At any time, the same legs that had carried me from Melmouth in a thoughtless panic might suddenly decide to turn me around and take me home. I do sometimes marvel that I had the courage to continue onward to the White Hart through the empty, half-lit woods.

Although my childhood had been a sheltered one, I had been fortunate enough to have seen some of the scenery beyond Melmouth’s walls. On the occasions I had been taken to London or to Bath, or to visit Lady Stavourley’s relations, our coach had set out upon the road on which I presently walked. As a girl, the sign of the White Hart had impressed me greatly. A large picture of a downy-coloured creature bearing a wide rack of antlers swung above the road. I had spent many journeys imagining what it would be like to tame and ride such a splendid animal. In my daydreams I would approach him with soft, beckoning words. He would bend his head and permit me to stroke his coat and to tie red silk ribbons on to his antlers.

As I came round the final bend in the road, the buck on the inn’s signboard roused my tears. My mind swirled with memories and confusion. I wept for myself, for the innocent girl whom I would never see again.

As it was mid-morning by the time I arrived, the White Hart bustled with activity. Its yard clattered with the sound of beasts and wheels. Outside, chickens clucked and pecked, scattering at the approach of

each pair of boots or wooden clogs. I saw no evidence of the mail coach or any indication of when it might arrive. My mind was a complete muddle. What was I to do? It was only then that I realized how little I knew about my proposed method of escape. I did not even know how much a fare would cost me, or if there was a direct route to my destination.

I held back from this hive of activity, attempting to gather my wits. I paced this way and that like a stray dog, and stanched my streaming nose and eyes against my sleeve.

You must understand, it all seemed desperately overwhelming. The tavern itself terrified me. I had never been alone in such a place. Even in daylight, these establishments could be loud and rough, filled with mud and men in heavy boots, raucous shouts and lewd behaviour. In the past, when I had travelled with Lord or Lady Stavourley, a private room upstairs would always be taken, so that our sensibilities would not be offended. Now, without a protector, without a footman or a servant, what would I do in such a place? I wished more than anything to avoid going inside, but my feet were so sore from the road and the damp had seeped through my skirts and given me a terrible chill. I looked longingly at the warm light of the fire through dusty, bevelled windows. Eventually, I steadied my nerve and approached the entry.