Mithridates the Great (28 page)

This was not going to do more than delay the cataphracts, but it would keep them busy long enough for the Roman infantry charge to hit them standing. The Romans did not bother with their usual preliminary shower of javelins, mainly because the Galatians and Thracians were already engaged, and would be far more affected by friendly fire than the well-protected Armenians. The infantry’s intention was to use their swords to slash at the unprotected shins and thighs of the Armenians, but the cataphracts did not give them the chance. Still struggling with the Roman cavalry, they chose the only possible line of disengagement – a line that sent them crashing into the advancing Armenian infantry.

Either at this point or slightly earlier, Lucullus decided that it was time for the rest of his infantry to make their presence known. Raising his sword, he bellowed ‘Soldiers, we are victorious’, and led the downhill charge. The Armenian baggage train was as confused as the rest of the army, and was keeping close behind the right flank on the assumption that the Romans were still some way ahead. The unexpected sight of Lucullus and his legionaries thundering downhill toward them prompted those manning the baggage train to retreat precipitately, directly away from the Roman advance – and again into the right of the Armenian infantry, which was by now in a state of total chaos.

Lucullus had achieved his initial objective – given his enemy’s overwhelming superiority in cavalry and missile troops, the last thing he had wanted was to be pinned by cavalry whilst his forces were picked off by bows and javelins. This was not an unreasonable fear, and exactly what the Parthians later did to Crassus. Instead, Lucullus had brought his men to close quarters with hardly a casualty, and his legions were now chewing through the right of the Armenian army whilst the rest of Tigranes’ force was still working out what had hit them.

Unsurprisingly, the Armenian right broke, and their panic communicated itself to the troops next in line. The baggage handlers were already in full flight along with much of the cavalry and to the unsteady Armenian levies it seemed that the battle was already lost. The same thought was preoccupying Tigranes, who had been off-balance since before the battle commenced, and who was keenly aware that the tumult of the Roman advance was getting uncomfortably close to his own position. This was the moment to make a headlong charge at the Romans and hope that the remainder of his army would take inspiration

from his valour. Of course, there was the embarrassing and all-too-likely prospect that this charge and Tigranes’ subsequent death would be in vain, which left the second option – to follow the example of those even nearer to the Romans, and make a timely exit from the battlefield.

Tigranes opted to depart, and with him went the last chance of Armenian arms salvaging anything from the day. The battle became a rout.

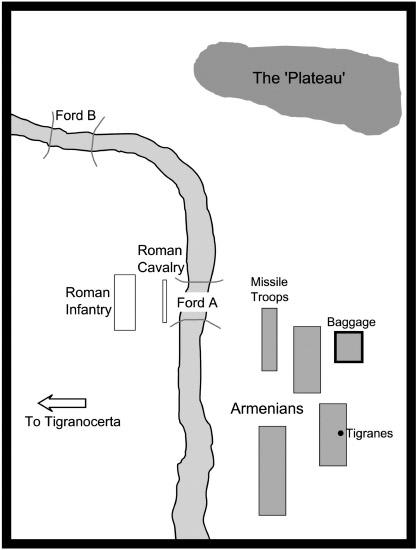

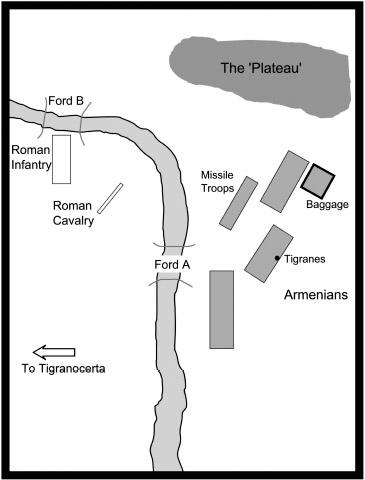

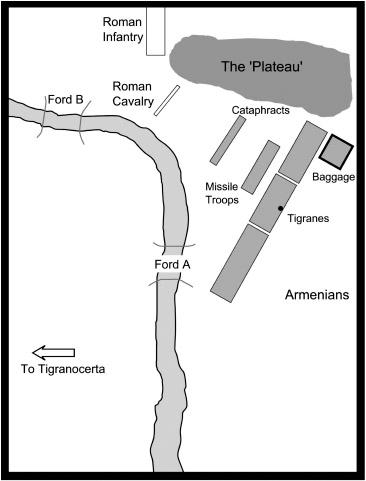

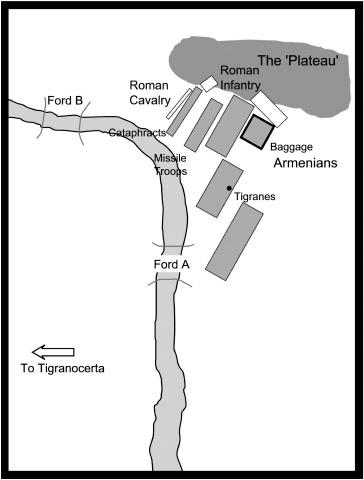

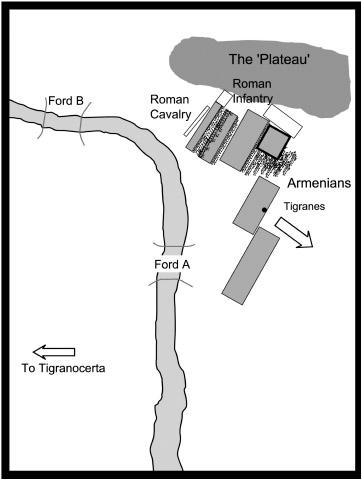

The following series of diagrams offer a highly speculative look at how the battle of Tigranocerta might have happened. Though this sequence is consistent with the available evidence, other interpretations are certainly possible. Tigranes’ army is in black, Lucullus in grey. Thin lines represent cavalry in skirmish order.

Battle of Tigranocerta

Phase I

Phase II

Phase III

Phase IV

Phase V

Phase VI

After Tigranocerta

Just as with the numbers of the army before the battle, the number of casualties afterwards are highly unreliable. For a start, it is improbable that anyone was counting, and secondly the Romans pursued the Armenian rout for a considerable distance. Therefore we get a body count as high as 100,000 (Plutarch) and as low as 5,000 (Phlegon). Nor are the two incompatible. If Plutarch drew his figures from claims that Tigranes lost 100,000 men and Phlegon says the Romans killed 5,000, it may be that 95% of the army lost their taste for soldiering and headed directly home without stopping to collect their back pay.

Lucullus was well aware that scattering an enemy army was not the same as destroying it, and he had given very strict orders that killing and not plunder was to be given priority. The Fimbrians, whatever their other faults, were a dependable force on the battlefield. But they would have been aware that tens of thousands of cavalry were still unaccounted for, and were not going to break into very small groups to hunt down their scattering foes.

Indeed, had they done so they would may well have come to grief, because there were probably 2,000 highly-disciplined cavalry close at hand. This was the personal guard of Mithridates who had been late arriving on the battlefield, quite possibly because he had a pretty good idea of what was going to happen there. If pessimism was indeed the cause of his tardiness, he would have been unsurprised to meet first a trickle and then a flood of panicked Armenian troops heading in the opposite direction. In any case, once he had ascertained that there would be no further fighting that day, he directed his energies to finding Tigranes. Given that Tigranes’ negotiating position had just sharply deteriorated, Mithridates now needed the goodwill of his son-in-law more than ever. Therefore he carefully refrained from pointing out that he had told Tigranes so. Instead he concentrated on raising the chastised king’s morale, handing over his personal guard with instructions that they should look after his crestfallen relative.

The Romans now received an unexpected bonus. The commander of the garrison of Tigranocerta, one Mancaeus, had witnessed the dispersal of the Armenian army from the walls. Given that the Romans were now in command of the land outside, he began to doubt the loyalty of his Greek mercenaries. Therefore he ordered them to hand in their weapons. This the Greeks took as a preliminary to their arrest and possible massacre, so they gathered together and started making themselves clubs from whatever heavy objects were at hand. When Mancaeus sent troops to disarm them once more, the mercenaries wound their cloaks about their shield arms and attacked with their makeshift weapons. Success gave them access to real weaponry from the defeated Armenian detachment. The Greeks fought their way to a section of the walls between the towers, and invited the delighted Romans to enter the city as their allies.

Finally the Fimbrians had all the plunder they could carry, though Lucullus reserved the state treasury for himself. For the next week or so he amused himself by having the Greeks in the city put on a series of plays and pageants before allowing any who so wished to return to the original homes from which Tigranes had forcibly transplanted them.

* One of the precautions the defenders of the city had taken was to lay in a stock of wasp nests and wild bears. When the Romans began the traditional attempt to undermine the walls of the city, the Pontic defenders countermined the tunnels and unleashed bears and wasps, singly and in combination, upon the Roman miners.

* This may or may not be the same person as Monima of Stratonice (p.41)

* One who listened to the Roman promises too attentively was King Zarbienus of the Gordyenians, who paid with his life for being a suspected conspirator.

* One of the first things Lucullus did on returning to Rome was to break the family connection with Clodius by filing for divorce.

Chapter 10

The Return of the King

King Mithridates to King Arsaces [of Parthia], greetings. ...

If you were looking at eternal peace with no perfidious enemies just beyond your borders, and if crushing the power of Rome would not bring you glory and fame, I would not dare to ask that you unite your prosperity with my misfortunes and join in an alliance....Fortune has deprived me of much, but has given in return the experience which underlies my advice.

1

So begins a letter to the king of Parthia from the new commander of the Armenian army, Mithridates of Pontus. Tigranes had belatedly seen the benefits of putting in charge someone with almost two decades of experience in fighting the Romans. While Lucullus was delayed in sorting out Tigranocerta, Mithridates was looking for allies and doing what he did best – raising another army. Whether the letter to Arsaces is genuine has been the heated topic of debate for centuries. It comes from the papers of Sallust, a contemporary historian. He might be quoting the letter verbatim from papers which later fell into Roman hands. Alternatively, he might have used a genuine letter as a topos, the basis for a literary exercise, or he might have invented the entire composition on the basis of what Mithridates

should

have said.