Mona Kerby & Eileen McKeating (3 page)

Read Mona Kerby & Eileen McKeating Online

Authors: Amelia Earhart: Courage in the Sky

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Women, #Juvenile Literature, #Juvenile Nonfiction, #Aeronautics; Astronautics & Space Science, #Earhart; Amelia - Juvenile Literature, #Women - Biography, #Science & Nature, #Adventurers & Explorers, #United States, #Air Pilots, #Air Pilots - United States - Biography - Juvenile Literature, #Historical, #Transportation, #Aviation, #Technology, #Earhart; Amelia

The Earharts lived in a large home and rented out some of the rooms. One of the renters was a young chemical engineer by the name of Sam Chapman. Sam and Amelia spent many hours together. Sam loved Amelia. He asked her to marry him, and for years, he waited for her answer. She always said no.

Sam believed that a wife should stay at home and take care of children. But a marriage like that hadn't made Amelia's parents happy. Besides, she insisted, women should have the same freedom as men. More than anything, Amelia wanted to be independent. She wanted a career of her own.

Still, a career in flying was the farthest thing from Amelia's mind. In World War I, a few thousand pilots took part in the bombing and fighting. But in 1920, stunt flying was about the only thing to do with a plane. For whatever reason, Amelia began attending air shows. Perhaps she remembered the little red plane.

One day, Amelia and her father stood on the sidelines and watched. “Dad, please ask that officer how long it takes to fly,” she said.

Mr. Earhart did. He told his daughter it took five to ten hours to learn.

“Please find out how much lessons cost,” Amelia continued.

“The answer to that is a thousand dollars. But why do you want to know?”

Amelia wasn't really sure. A few days later, one of the pilots took her up in his plane. From her seat behind the pilot, Amelia saw the ocean. She saw the Hollywood Hills. And suddenly, everything became clear to Amelia. There was only one thing to do. As she wrote later in her book,

The Fun of It,

“I knew I myself had to fly.”

The Fun of It,

“I knew I myself had to fly.”

4

Top Speed

Amelia turned over in bed and crackled. With each toss and turn, she crackled some more. The next morning, she looked at herself in the mirror. It was better. Still, she slept in it another night.

It was 1922 and Amelia had just bought a real leather jacket. Now, she looked like a true flyer. But the other pilots' jackets were worn. Hers was too shiny and new. So, for three nights, Amelia slept in her coat. “There just had to be some wrinkles,” she explained.

Soon after her first plane ride, Amelia signed up for lessons. She expected her parents to pay for them. They didn't. Mr. and Mrs. Earhart didn't mind if Amelia wanted to fly. But they didn't have a thousand dollars to spare.

Amelia didn't give up. She took a job in the post office. To earn some extra money, she did some photography work. She also found a flyer who would teach her and let her pay when she had the money. Her teacher's name was Neta Snook and she was one of the first women pilots in the world. Like Amelia, she wore a leather jacket, wrinkled.

When Amelia flew, she also wore a padded leather helmet, goggles, shirt, scarf, tight-fitting pants, and leather boots that laced up to her knees. One reason she dressed this way was because she wanted to look exactly like the other pilots, or aviators, as they were called. (“AY-vee-ay-ters.”) A woman pilot was called an aviatrix (“ay-vee-AY-tricks”). But the main reason she dressed this way was because flying was dirty, dusty, and rough.

In those days, runways weren't concrete; they were dirt or grass. At every takeoff and landing, there was a whirlwind of dust. Up in the air in open cockpits, aviators felt the snow, sleet, rain, and hail. In cold weather, they smeared grease on their faces to keep them from freezing. Leather coats and helmets protected aviators from the weather and from bumps and scrapes during rough rides. Goggles kept bugs and dirt out of their eyes.

At first, airplanes were known by their British name, “aeroplanes” (“AIR-uh-playns”). They were also called ships. In a way, they sailed in the air just as boats sailed in the sea.

These aeroplanes were very light. On the ground, aviators pushed them around by their tails. Planes didn't have a metal body. Instead, they were covered with cloth. In the air, top speed was 80 miles per hour. This is not much faster than the speed limit on today's highways.

Aviators steered their “ships” with their hands on a control stick and with their feet on a rudder bar. They made the aeroplanes go up and down by moving the control stick forward and backward. They turned their planes from left to right by moving the control stick from side to side.

They also turned the plane by pressing on the rudder bar with their feet. This bar was attached to the rudder, a wooden flap on the tail of the plane. In the air, the rudder bar shook and shivered and throbbed. In fact, it vibrated so much that after a few minutes, Amelia's feet always went to sleep.

She loved every minute of it. “It's so breathtakingly beautiful up there,” she explained. “I want to fly whenever I can.” Soon, other aviators were calling Amelia a natural. Not only could she fly, but she could also repair a plane's engine and sew up the rips in the plane's body.

But in those days, women were not supposed to fly. Plenty of people, including Sam, reminded Amelia that women should be ladies. They should pin their hair neatly in a bun, get married, and stay home.

No doubt, Amelia worried about the proper way to act. In the end, however, she made up her own mind. In the summer of 1922, she cut off her long hair. Then she bought a bright yellow secondhand Kinner Canary Aeroplane. She spent all of her savings and all of Muriel's savings. She even used her mother's money to buy the plane.

And, she earned the only kind of flying license issued at the time. There were possibly twelve women in the entire world with such a license. Amelia Earhart was one of them.

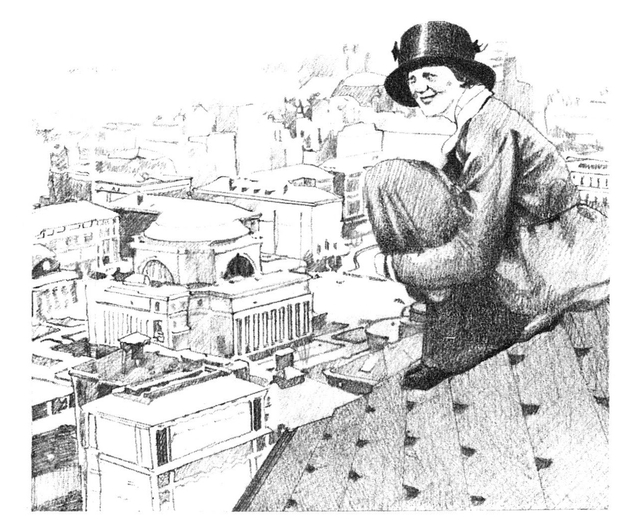

That fall, Amelia set her first air record by becoming the first woman to fly at 14,000 feet. A few weeks later, she was trying to fly higher, when trouble hit. Blinded by snow and clouds, Amelia had no idea if she was flying right side up, sideways, or upside down. She spun the plane nose down, turning over and over for 12,000 feet. At 3,000 feet, the clouds broke and Amelia could see. When she landed, she was shaking. As she told her friends, good pilots don't worry too much.

For the next few years, Amelia worked during the week and flew on the weekends. After all, there weren't any careers for women in flying. She was flying for the sheer “fun of it.” Then, once again, something happened that changed her life.

In 1924, Amelia's parents divorced. They were no longer happy together. Edwin remained in California. Amy wanted to go East to Boston, where Muriel was in school. Amelia sold her plane and bought a bright yellow roadster, a type of car with a cloth top. In the 1920s, there weren't any paved highways, just dirt roads. There weren't many gasoline stations and no fast-food restaurants along the way.

Late in the spring of 1925, Amelia and her mother headed East in Amelia's car. They set out to cross the entire country, alone. This trip might have stopped some people. It didn't stop Amelia.

5

The Important Question

Amelia and her mother rolled into Boston. Their car windows were full of stickers from all the places they had visited.

Within a week, Amelia was in the hospital. For years, she had suffered from terrible headaches. Flying had made them worse. In the Boston hospital, a piece of bone was removed from Amelia's nose. This operation helped her sinuses to drain and made her head feel better. Unfortunately, however, any time Amelia was under stress, she got a headache.

But a little pain never stopped Amelia for long. Soon, she was ready for work. She found a job helping families who were new to the United States. She taught the children English and other useful skills. Since many of them had never ridden in a car, Amelia often drove the children around the block.

People liked Amelia. She was quiet and pleasant. But in 1927, Amelia Earhart was an unusual woman. Though few people at work knew it, Amelia was spending her spare time with planes. She flew them, repaired them, and talked about them with other pilots. Some of her family thought she was odd. Only her mother encouraged her. Years later, Amy wrote, “I realized that if she wanted to be a flyer someone in the family had to be interested.”

Certainly Sam Chapman didn't understand Amelia. He changed jobs and followed her to Boston. To Sam's way of thinking, it was time for Amelia to become his wife and stop these foolish ideas of having a career. After all, she was thirty years old. Amelia told her sister, “I know what I want to do and I expect to do it, married or single.”

But more than likely, Amelia had no idea what she wanted to do. One afternoon in 1928, when she was teaching, she received a phone call. “Tell 'em I'm busy,” Amelia said.

“Says it's important,” came the reply.

When Amelia picked up the phone, a man asked her a question which changed her life.

She agreed to meet with the man and some of his friends that evening. Their talk centered on the important question, “Would you like to fly the Atlantic?” There was only one answer for Amelia. “Yes,” she replied.

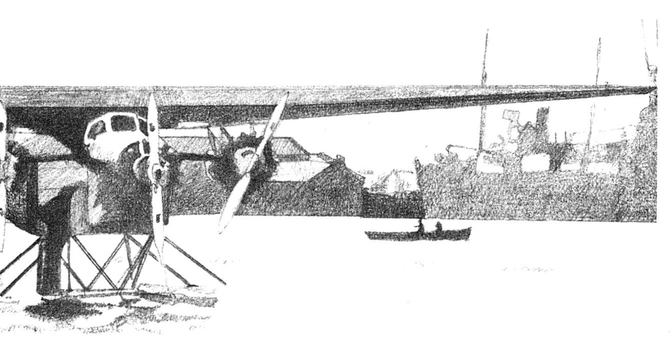

In 1928, only seven planes had successfully crossed the Atlantic Ocean. No woman had ever made the trip.

Mrs. Amy Guest of England bought a plane and hired a crew. She wanted to be the first woman to fly across the Atlantic Ocean. Her family was afraid for her to make the trip. She asked George Palmer Putnam of the American publishing company to find a woman pilot to take her place.

The year before, Putnam's company had published the pilot Charles Lindbergh's story, We, about his own flight across the ocean. Putnam was eager to sell another book and make some more money. He found a woman pilotâAmelia Earhart.

Mrs. Guest paid for the flight. She made Amelia captain of the plane, and said that Amelia would make all the decisions during the flight. However, Amelia would not fly the plane since she did not have as much experience as the crew. And she would not get any money. The pilot Wilmer (Bill) Stulz received $20,000 while the mechanic Lou (Slim) Gordon received $5,000.

Other books

The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian Dynasty by Ilan Pappe

The Journey Prize Stories 27 by Various

The Billionaire’s Lust (His Submissive, Part Seven) by Ava Claire

Las lunas de Júpiter by Isaac Asimov

Tea-Totally Dead by Girdner, Jaqueline

The Return by Dayna Lorentz

Vanished by Sheela Chari

Chaos Choreography by Seanan McGuire

Yellow Ghost: La Femme Selita Prequel by Lace, Lolah

Justice for Hire by Rayven T. Hill