Moneyball (Movie Tie-In Edition) (Movie Tie-In Editions) (16 page)

Read Moneyball (Movie Tie-In Edition) (Movie Tie-In Editions) Online

Authors: Michael Lewis

Tags: #Sports & Recreation, #Business Aspects, #Baseball, #Statistics, #History, #Business & Economics, #Management

“Fielder could help us here,” says Chris Pittaro, finally.

Fielder is the semi-aptly named Prince Fielder, son of Cecil Fielder, who in 1990 hit fifty-one home runs for the Detroit Tigers, and who by the end of his career could hardly waddle around the bases after one of his mammoth shots into the upper deck, much less maneuver himself in front of a ground ball. “Cecil Fielder acknowledges a weight of 261,” Bill James once wrote, “leaving unanswered the question of what he might weigh if he put his other foot on the scale.” Cecil Fielder could have swallowed Jeremy Brown whole and had room left for dessert, and the son apparently has an even more troubling weight problem than his father. Here’s an astonishing fact: Prince Fielder is too fat even for the Oakland A’s. Of no other baseball player in the whole of North America can this be said. Pittaro seems to think that the Detroit Tigers might take Fielder anyway, for sentimental reasons. And if the Tigers take him, they trigger a chain reaction that ends with the Mets getting one of their first six choices.

Before anyone has a chance to figure out whether Kazmir will get to the Mets, the draft begins. As it does, the Oakland A’s owner, Steve Schott, enters the room, followed shortly by the A’s manager, Art Howe. Howe stands in the back of the room with his jaw jutting and a philosophical expression on his face, the way he does in the dugout during games. It is one of the mysteries of baseball that people outside it assume the manager is in charge of important personnel decisions. From the start to the end of this process Howe has been, as he is with all personnel decisions, left entirely in the dark.

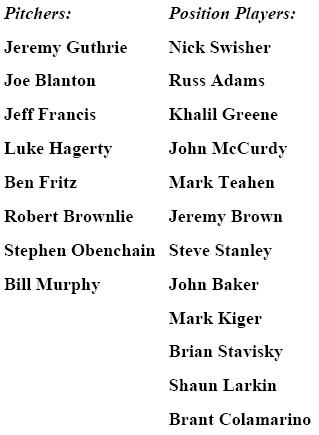

The A’s scouting director, Erik Kubota, takes up his position at the speakerphone and tells everyone else to shut up. Everyone in the draft room is about to learn just how new and different is the Oakland A’s scientific selection of amateur baseball players. The A’s front office has a list, never formally written out, of the twenty players they’d draft in a perfect world. That is, if money were no object and twenty-nine other teams were not also vying to draft the best amateur players in the country. The list is a pure expression of the new view of amateur players. On it are eight pitchers and twelve hitters—all, for the moment, just names.

Two of the position players—Khalil Greene and Russ Adams—Billy already knew would be gone before the A’s picked, and so he hadn’t even bothered to discuss them during the meetings. His best friend J. P. Ricciardi would take Adams, and another close friend, Kevin Towers, the GM of the San Diego Padres, would take Greene. Two of the pitchers—Robert Brownlie and Jeremy Guthrie—were represented by the agent Scott Boras. Boras was famous for extracting more money than other agents for amateur players. If the team didn’t pay whatever Boras asked, Boras would encourage his client to take a year off of baseball and reenter the draft the following year, when he might be selected by a team with real money. The effects of Boras’s tactics on rich teams were astonishing. In 2001 the agent had squeezed a package worth $9.5 million out of Texas Rangers owner Tom Hicks for a college third baseman named Mark Teixeira. The guy who was picked ahead of Teixeira signed for $4.2 million, and the guy who was picked after him signed for $2.65 million, and yet somehow between these numbers Boras found $9.5 million. By finding the highest bidders for his players before the draft and scaring everyone else away from them, Boras was transforming the draft into a pure auction.

Billy couldn’t afford auctions. He had $9.5 million to spend and Boras had let it be known that whichever team drafted Jeremy Guthrie was going to cough up a package worth $20 million—or Guthrie would return to Stanford for his senior year. The Cleveland Indians had agreed to pay the price, and so the Indians would take Guthrie with the twenty-second pick.

Of the sixteen players on his list he could afford, and stood any chance of getting, Billy thinks he might land as many as six. But the truth is he doesn’t know. It was possible he’d only get one of the players on the wish list. By the time the A’s made their second pick, the twenty-fourth of the draft, all of them might be gone. If they got six of the players on their wish list, Paul said, they’d be ecstatic. No team ever came away with six of their top twenty.

The room remains silent. The entire draft takes place over speakerphone, far away from the fans. In the draft Major League Baseball has brought to life Bill James’s dystopic vision of closing the stadium to the fans and playing the game in private. Pro football and pro basketball make great public event of their drafts. They gather their famous coaches and players in a television studio and hand them paddles with big numbers on them to wave. Football and basketball fans are able to watch the future of their team unfold before their eyes. The Major League Baseball draft is a conference call—now broadcast on the Web.

The Pittsburgh Pirates, owners of the worst regular season record in the 2001 season, have the first overall pick. A voice from Pittsburgh crackles over the speakerphone:

“Redraft number 0090. Bullington, Bryan. Right-handed pitcher. Ball State University. Fishers, Indiana.”

Just like that the first $4 million is spent, but at least it is spent on a college player. (“Redraft” means he has been drafted before.) The next five teams, among the most pathetic organizations in pro baseball, select high school players. Tampa Bay takes a high school shortstop named Melvin Upton; Cincinnati follows by taking the high school pitcher Chris Gruler; Baltimore follows suit with a high school pitcher named Adam Loewen; Montreal follows suit with yet another high school pitcher, Clinton Everts. The selections made are, from the A’s point of view, delightfully mad. Eight of the first nine teams select high schoolers. The worst teams in baseball, the teams that can least afford for their draft to go wrong, have walked into the casino, ignored the odds, and made straight for the craps table.

Billy and Paul no longer think of the draft as a crapshoot. They are a pair of card counters at the blackjack tables; they think they’ve found a way to turn the odds inside the casino against the owner. They think they can take over the casino. Each time a team rolls the dice on a high school player, Billy punches his fist in the air: every player taken that he doesn’t want boosts his chances of getting one he does want. When the Milwaukee Brewers take Prince Fielder with the eighth pick, the room explodes. It means that Scott Kazmir probably will be available to the Mets. And he is. And the Mets take him. (And spend $2.15 million to sign him.) Sixteen minutes into the draft Erik Kubota leans into the speakerphone, trying, and nearly succeeding, to sound cool and collected.

“Oakland selects Swisher, Nicholas. First baseman/center fielder. Ohio State University. Parkersburg, West Virginia. Son of ex-major leaguer Steve Swisher.”

“Prince Fielder just saved our paint,” says an old scout. Even the fat players who don’t work for the A’s do the A’s work.

Billy is now on his feet. He’s got Swisher in the bag: who else can he get? There’s a new thrust about him, an unabridged expression on his face. He was a bond trader, who had made a killing in the morning and entered the afternoon free of fear. Feeling greedy. Certain that the fear in the market would present him with even more opportunities to exploit. Whatever happened now wasn’t going to be bad. How good could it get? The anger is gone, lingering only as an afterthought in other people’s minds. He was no longer in the batter’s box. He was out in center field, poised to make a spectacular catch no one expected him to make. “Billy’s a shark,” J. P. Ricciardi had said, by way of explaining what distinguished Billy from every other GM in the game. “It’s not just that he’s smarter than the average bear. He’s relentless—the most relentless person I have ever known.”

Billy moves back and forth between his wish list and Paul and Erik. Paul to check his judgments, Erik to execute his wishes. Like any good bond trader, he loves making decisions. The quicker the better. He looks up at the names of the players on the white board and listens to the speakerphone crackle. Three pitchers from the wish list (Francis, Brownlie, and Guthrie) go quickly. Sixteen players that he badly wants to own remain at large. The A’s second first-round pick is #24 (paid to them by the Yankees for the right to buy Jason Giambi), followed rapidly by #26, #30, #35, #37, #39. Billy has agreed with Erik and Paul to use #24 to get John McCurdy, a shortstop from the University of Maryland, the second hitter on the wish list. McCurdy was an ugly-looking fielder with the highest slugging percentage in the country. They’d turn him into a second baseman, where his fielding would matter less. Billy thought McCurdy might be the next Jeff Kent.

The White Sox come on the line. “Here goes Blanton,” says Billy.

When Kenny Williams told Billy an hour before that the White Sox were taking Blanton, Billy couldn’t but agree that it showed disturbingly good judgment. Blanton was the second best pitcher in the draft, in Billy’s view, behind Stanford pitcher Jeremy Guthrie.

A White Sox voice crackles on the speakerphone: “The White Sox selects redraft number 0103, Ring, Roger. Left-handed pitcher. San Diego State University. La Mesa, California.”

“You fucking got to be kidding me!” hollers Billy, overjoyed. He doesn’t pause to complain that Kenny Williams had told him he was taking Blanton. (Was he afraid Billy might take Ring?) “Ring over Blanton? A reliever over a starter?” Then it dawns on him: “Blanton’s going to get to us.” The second best right-handed pitcher in the draft. He says it but he can’t quite believe it. He looks at the board and recalculates what the GMs with the next five picks will do. “You know what?” he says in a surer tone. “Blanton’s going to be there at 24.”

“Blanton

and

Swisher,” says Erik. “That’s a home run.”

“The Giants won’t take McCurdy, right?” says Billy. The San Francisco Giants had the twenty-fifth pick, the only pick between the A’s next two. “Take Blanton with 24 and McCurdy with 26.”

“Swisher and Blanton

and

McCurdy,” says Erik “This is unfair.” He clicks the button on the speakerphone, and his voice shaking like a man calling in to say he holds the winning Lotto ticket, takes Blanton with the twenty-fourth pick, pauses while the Giants make their pick, then takes McCurdy with the twenty-sixth.

Everyone in the room, even the people in the back who have no real idea what is going on, a group that includes both the manager and the owner of the Oakland A’s, claps and cheers. The entire room assumes that if Billy gets what he wants it can only be good for the future of the franchise. This is now the Billy Beane Show, and it’s not over yet.

Billy stares at the board. “Fritz,” he says. “It’d be unbelievable if we could get Fritz too.” Benjamin Fritz, right-handed pitcher from Fresno State. Third best right-handed pitcher in the draft, in the opinion of Paul DePodesta’s computer.

“There’s no chance Teahen’s gone before 39, right?” says Paul quickly. He can see what Billy is doing. Having realized that he can get most of the best hitters, Billy is now seeing if he can get the best pitchers, too. Paul’s view—the “objective” one—is that the hitters are a much better bet than the pitchers. He thinks the best thing to do with pitchers is draft them in bulk, lower down. He doesn’t want to risk losing his hitters.

“Teahen will be there at 39,” says Billy.

No one else in the room is willing to confirm it.

“Take Fritz with 30, Brown with 35, and Teahen with 37,” Billy says. Erik leans into the speakerphone, and listens. The Arizona Diamondbacks take yet another high school player with the twenty-seventh pick and the Seattle Mariners take another with the twenty-eighth. The Astros take a college player, not Fritz, with the twenty-ninth. Erik takes Fritz with the thirtieth.

“We just got two of the three best right-handed pitchers in the country, and two of the four best position players,” says Paul.

“This doesn’t happen,” says Billy. “Don’t think this is normal.”

As the thirty-fifth pick approaches, Erik once again leans into the speaker phone. If he leaned in just a bit more closely he might hear phones around the league clicking off, so that people could laugh without being heard. For they do laugh. They will make fun of what the A’s are about to do; and there will be a lesson in that. The inability to envision a certain kind of person doing a certain kind of thing because you’ve never seen someone who looks like him do it before is not just a vice. It’s a luxury. What begins as a failure of the imagination ends as a market inefficiency: when you rule out an entire class of people from doing a job simply by their appearance, you are less likely to find the best person for the job.

When asked which current or former major league player Jeremy Brown reminded him of, Paul stewed for two days, and finally said, “He has no equivalent.” The kid himself is down in Tuscaloosa, listening to the Webcast of the conference call, biting his nails because he

still

doesn’t quite believe that the A’s will take him in the first round. He’s told no one except his parents and his girlfriend and them he’s made swear they won’t tell anyone else, in case it doesn’t happen. Some part of him still thinks he’s being set up to be a laughingstock. That part of him dies the moment he hears his name called.