Moneyball (Movie Tie-In Edition) (Movie Tie-In Editions) (30 page)

Read Moneyball (Movie Tie-In Edition) (Movie Tie-In Editions) Online

Authors: Michael Lewis

Tags: #Sports & Recreation, #Business Aspects, #Baseball, #Statistics, #History, #Business & Economics, #Management

“Oh, hi Ricardo.” It’s Ricardo Rincon, who is Mexican, and normally gives his interviews through an interpreter.

“Ricardo, I know it’s a little bit shocking for you,” says Billy. His syntax changes slightly, he’s groping for a Mexican mode of expression and winds up saying whatever he can think of that Ricardo might understand. “But we have been trying to get you for a long time. You’re going to love the guys on the team. They’re fun.”

Ricardo is trying to get it clear in his head that he’s supposed to do what he’s just been asked to do, take off his Cleveland Indians uniform, gather his personal belongings, and walk down the hall into the Oakland clubhouse and put on an Oakland uniform. He can’t quite get his mind around it.

“Yes! Yes!” says Billy. “I don’t know if you’ll pitch tonight. But you’re on

our

team tonight.”

Whatever Ricardo says he means:

Oh my God, I might actually have to pitch tonight?

“Yes. Yes. Possibly you’ll punch out Jim Thome!”

Possibly you will punch out Jim Thome.

Billy is becoming, quickly, a Mexican immigrant.

“We’ll have a uniform and everything ready for you.”

And everything.

He’s had just about enough touchy-feely for one evening. He tries to lead the conversation to a not horribly unnatural conclusion. “Where are you from, Ricardo?”

Ricardo says he’s from Veracruz, Mexico.

“Well, Veracruz is closer to here than to Cleveland. You’re closer to home!”

He finishes that one, hangs up, and says, “It’s gotten to be a longer road trip for Ricardo than he expected.” He looks absolutely spent. The wad of tobacco is gone from his upper lip and his mouth is dry. He gargles with the glass of water on his desk, and spits. “I’ve got to work out,” he says.

At that moment Mike Magnante was removing his Oakland uniform and Ricardo Rincon was removing his Cleveland one. Mags quickly left the Oakland clubhouse; he’d come back for his things later when no one was around. His wife had brought the kids to the game so he couldn’t just leave. Magnante watched the game with his family until the sixth inning, and then left so he wouldn’t have to answer questions from the media. He had no desire to call further attention to his situation. In his youth he might have mouthed off. He would certainly have borne a grudge. But he was no longer young; the numbness had long since set in. He thought of himself the way the market thought of him, as an asset to be bought and sold. He’d long ago forgotten whatever it was he was meant to feel.

The main thing was that Mags was gone from the clubhouse before Billy walked across to change into his sweats. As Billy headed in, however, he bumped into Ricardo Rincon heading out, in street clothes. Ricardo remained confused. He had heard he was going to the San Francisco Giants, or maybe the Los Angeles Dodgers. He’d never imagined he might be an Oakland A. And he still doesn’t understand the full implications of what’s happened. The Oakland A’s only left-handed relief pitcher is going out to find a seat in the stands to watch the game. Billy leads him back into the clubhouse where the staff has just finished steaming

RINCON

onto the back of an Oakland A’s jersey. “You’re on our team now,” says Billy.

Ricardo Rincon walked back into his new clubhouse, put on his new uniform, and sat down and watched the entire game on television. “I was not ready,” he said. “I couldn’t concentrate.” His left arm, however, felt great.

Chapter Ten

ANATOMY OF AN UNDERVALUED PITCHER

A

FTER BILLY ACQUIRED

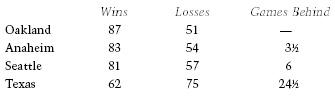

Ricardo Rincon and Ray Durham, the team went from good to great. The only team in the past fifty years with a better second half record than the 2002 Oakland A’s was the 2001 Oakland A’s, and even they were just one game better. On the evening of September 4, the standings in the American League West were, with the exception of the Texas Rangers, an inversion of what they had been six weeks before.

The Anaheim Angels were the second hottest team in baseball. They’d won thirteen of their last nineteen games, and yet lost ground in the race. The reason for this was that the Oakland A’s had won

all

of their previous nineteen games—and tied the American League record for consecutive wins. On the night of September 4, 2002, before a crowd of 55,528, the largest ever to see an Oakland regular season game, they had set out to do what no other team had done in the 102-year history of the league: win their twentieth game in a row. By the top of the seventh inning, up 11–5 against the Kansas City Royals, with Tim Hudson still pitching, the game seemed all but over.

Then, suddenly, Hudson’s in trouble. After two quick outs he gives up one single to Mike Sweeney and another, harder hit, to Raul Ibanez. Art Howe emerges from the dugout and glances at the bullpen.

What turned up in the A’s bullpen seemed to vary from one night to the next. On this night the less important end of the bench held a cynical, short, lefty sidewinder Billy Beane had tried and failed to give away, Mike Venafro, and two guys newly arrived from Triple-A: Jeff Tam and Micah Bowie. On the more important end of the bench was a clubfooted screwball pitcher with knee problems; a short, squat Mexican left-hander who spoke so little English that he called everyone on the team “Poppy”; and a tempestuous flamethrower with uneven control of self and ball. Jim Mecir, Ricardo Rincon, Billy Koch. Of the entire bullpen, in the view of the Oakland A’s front office, the most critical to the team’s success was a mild-mannered Baptist whose delivery resembled no other pitcher in the major leagues: Chad Bradford. Billy has instructed Art Howe to bring in Bradford whenever the game is on the line. In most cases when Bradford came out of the pen, the game was tight and runners were on base. Tonight, the game isn’t tight; tonight, history is calling Chad Bradford in from the pen.

Art Howe pulls his right hand out of his jacket and flips his fingers underhanded, like a lawn bowler. Taking his cue, Bradford steps off the bullpen mound and walks toward the field of play. Before reaching it, he pulls the bill of his cap down over his face and fixes his eyes on the ground three feet in front of him. He’s six foot five but walks short. Really, it’s a kind of vanishing act: by the time he steps furtively over the foul line, he’s shed himself entirely of the interest of the crowd. If you didn’t know who he was or what he was doing you would say he wasn’t making an entrance but a getaway.

Baseball nourishes eccentricity and big league bullpens have seen their share of self-consciously colorful oddballs. Chad Bradford was the opposite. He didn’t brush his teeth between innings, like Turk Wendell, or throw temper tantrums on the mound, like Al Hrabosky. He didn’t stomp and glare and leap dramatically over the foul lines. His mother, back home in Mississippi, often complained about her son’s on-field demeanor. Specifically, she complained that he never did anything to let people know how handsome and charming he actually was. For instance, he never allowed the television cameras to see his winsome smile, even when he sat in the dugout after a successful outing. Chad never smiled because he was mortified by the idea of the TV cameras catching him smiling—or, for that matter, doing anything at all.

None of it helps his cause of remaining inconspicuous. Once he’s on the mound, nothing he does can wall him off from the crowd or the cameras. He makes his living on the baseball field’s only raised platform, and in such a way as to call to mind a circus act. Sooner or later he needs to throw his warm-up pitches, and, when he does, fans who have never seen him pitch gawk and point. In their trailers outside the stadium TV producers scramble to assemble the tape the announcers will need to explain this curiosity. Pitching out of the stretch, he does not rear up and back, like other relief pitchers. He jackknifes at the waist, like a jitterbug dancer lurching for his partner. His throwing hand swoops out toward the plate and down toward the earth. Less than an inch off the ground, way out where the dirt meets the infield grass, he rolls the ball off his fingertips. When subjected to slow-motion replay, as this motion often is, it looks less like pitching than feeding pigeons or shooting craps. The announcers often call him a sidearm pitcher, but that hasn’t been true of him for nearly four years. He’s now, in baseball lingo, a “submariner,” which is baseball’s way of making a guy who throws underhand sound manly.

The truth is that there is no good word to describe Chad Bradford’s pitching motion; “underhand” doesn’t capture the full flavor of it. This year, for the first time in his career, Chad Bradford’s knuckles have scraped the dirt as he throws. Once during warm-ups his hand bounced so violently off the ground that the baseball ricocheted over the startled head of Toronto Blue Jays’ outfielder Vernon Wells, minding his own business in the on-deck circle. ESPN had replayed that one, over and over. Chad’s new fear is that he’ll do it again, in a game, and that the television cameras will catch him at it, and everyone will be paying him attention all over again.

The odd thing about Chad Bradford is that he wants so badly to be normal. Normal is what he’s not. It’s not just that he throws funny. His idiosyncratic streak runs straight down to the bottom of his character. Back in high school he had this shiny white rock he sneaked out with him to the mound. He’d noticed it one day when he was pitching. He was pitching especially well that day and the rock didn’t look like any rock he’d ever seen on the mound. He attributed some part of his success to the presence of the shiny white rock. When he was done pitching, he picked up the rock and carried it home with him. For the next three years he never ventured to the pitcher’s mound without his rock. He’d sneak it out with him in his pocket and put it on the mound, just so, and in such a way that no one ever noticed.

By the time he reached the big leagues, he’d weaned himself of his lucky rock but not of the frame of mind that created it. He had the tenacious sanity of the slightly mad. A big league pitcher who wishes to avoid attention, Chad Bradford has learned to disguise his superstitions as routines. There are things he always does—like throwing exactly the same number of pitches in the bullpen, in exactly the same order; or like telling his wife to leave the stadium the moment he enters a game. There are things he never does—like touch the rosin bag.

His twin desires—to succeed, and to remain unnoticed—grow less compatible by the day. Chad Bradford’s 2002 statistics imply, to the A’s front office, that he is not just the best pitcher in their bullpen but one of the most effective relief pitchers in all of baseball. The Oakland A’s pay Chad Bradford $237,000 a year, but his performance justifies many multiples of that. At one point the Oakland A’s front office says that if Bradford simply continues doing what he’s done he’ll one day be looking at a multi-year deal at $3 million plus per. The wonder isn’t merely that they have him so cheaply, but that they have him at all. The wonder is that, until they snapped him up for next to nothing, nobody in the big leagues paid any attention at all to Chad Bradford.

In this respect, if no other, Chad Bradford resembled a lot of the Oakland A’s pitchers. The A’s had the best staff in the American League and yet of all their pitchers only Mark Mulder, one of the team’s three brilliant starters, had failed to inspire serious doubts at some point in his career in the baseball scouting mind. The team’s second ace, Tim Hudson, was a short right-handed pitcher who couldn’t get himself drafted at all in 1996, after his junior year in college, and then not until the sixth round of the 1997 draft. The team’s third ace, Barry Zito, had been spat upon by both the Texas Rangers, who took him in the third round of the 1998 draft but declined to pay him the $50,000 required to sign him, and the San Diego Padres, for whom Zito privately auditioned and badly wanted to play. The Padres told Zito that he didn’t throw hard enough to make it in the big leagues. The Oakland A’s disagreed and selected him with the ninth pick of the 1999 draft. Three years later a top executive for those same San Diego Padres would say that the reason the Oakland A’s win so many games with so little money is that “Billy got lucky with those pitchers.”

And he did. But if an explanation is where the mind comes to rest, the mind that stopped at “lucky” when it sought to explain the Oakland A’s recent pitching success bordered on narcoleptic. His reduced circumstances had forced Billy Beane to embrace a different mental model of the Big League Pitcher. In Billy Beane’s mind, pitchers were nothing like high-performance sports cars, or thoroughbred racehorses, or any other metaphor that implied a cool, inbuilt superiority. They were more like writers. Like writers, pitchers initiated action, and set the tone for their games. They had all sorts of ways of achieving their effects and they needed to be judged by those effects, rather than by their outward appearance, or their technique. To place a premium on velocity for its own sake was like placing a premium on a big vocabulary for its own sake. To say all pitchers should pitch like Nolan Ryan was as absurd as insisting that all writers should write like John Updike. Good pitchers were pitchers who got outs; how they did it was beside the point.