Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting (41 page)

Read Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting Online

Authors: W. Scott Poole

Set primarily in the fictional Louisiana town of Bon Temps,

True Blood

intertwines its living dead in a rich regional mythology, a dirty Southern world of pickup trucks, juke joints, and evangelical religion as a patina for a seamy and steamy world of sex and violence. The series follows the fortunes of a Sookie Stackhouse and her beau, the century-old vampire and Confederate veteran Bill Compton. Bill and Sookie attempt to find vampire–human love in a modern America in which vampires have “come out of the closet” after the discovery and marketing of a blood substitute known as “Tru Blood.”

The modern American setting, and the willingness to explore sexuality with humor and frankness, has made the show, in its third season

at the time of writing, both a controversial and a critically acclaimed hit. Series creator Alan Ball sees himself as not so much revising the vampire myth as returning it to its roots and giving it an American, indeed a Southern, accent. This has allowed for all manner of satire and comment, especially in relation to America’s struggle to come to terms with sexual identity and the rights of sexual minorities. In this,

True Blood

is the antithesis of

Twilight

, a point that series creator Alan Ball made when he told

Rolling Stone

, “Vampires are sex. I don’t get a vampire story about abstinence.”

54

True Blood

Cast

True Blood

envelops its viewers in a sometimes uncomfortably alternative sensuality that encourages an equally uncomfortable social critique.

Twilight

represents a supernatural escape from the historic demands of feminism and the results of the sexual revolution. In some ways, the popularity of these franchises highlights the American cultural divide, the two Americas of the culture wars. The zombie genre has, meanwhile, taken a strongly political turn as well, becoming, since 2001, a standing (or rather shambling and stumbling) critique of America’s foreign and domestic policy since 9/11.

Zombie Crawl Through History

Zombie narratives have proven the perfect vehicle for social satire. This is not because of any inherent quality of the zombie as a character but rather because zombies always bring an apocalypse with them. Any apocalyptic narrative represents a deconstruction of the social contract, either as a complete revolution, a fairly severe redefinition, or, in the case of evangelical eschatology, a reactionary insistence that breaks with a traditional past have triggered God’s judgment. Imagining the world as we know it collapsing around us gives us the opportunity to take a long look at what that dead world valued and call it into question.

Moreover, zombies are, more than any other monster, truly human. The vampire is a fully transformed human being, in essence a superior being and the aristocracy of the monster world. Other creatures of the night have little or no human connection, born from beyond the stars or out of satanic darkness. The zombie, on the other hand, is one of us. They are recognizably human even as their bodies are always shown in varying states of decay. Romero’s films often emphasized this by making zombies representative of specific occupations and pastimes ranging from cheerleader zombies to zombie brides and zombie doctors.

Zombie films often force our identification with the walking dead by revealing human beings as the real monsters. In Romero’s

Night of the Living Dead

, the besieged humans cannot put aside their own desire for power and control in order to help one another. Frequently, humans murdering zombies with abandon and relish are some of the more frightening scenes in the best zombie films. Almost every zombie feature ends in the death of the major characters because of their own pride, self-absorption, or tyrannical impulses.

55

Apocalyptic narratives in which everyday people are transformed into monsters allows for significant social critique. Although George Romero has frequently insisted that

Night of the Living Dead

offers no political satire, audiences of the film have read it as a statement about both the Vietnam War and American racism. Romero’s later films suggest that he crafted them around efforts to critique American society. The 2005

Land of the Dead

, for example, alluded both to the war in Iraq and to the American class structure.

Diary of the Dead

(2008)is a send-up of reality TV, celebrity culture, and America’s growing reliance on the Internet for news and social interaction.

56

Horror auteurs in recent years have used the zombie genre not only to launch a broad critique of American society but also to comment on particular political issues. Joe Dante’s 2005 “Homecoming,” an episode in Showtime’s

Masters of Horror

series, features a right-wing

commentator named David Murch. On a popular cable television show, Murch tells a mother who lost her son in Iraq that if he could have “one wish” it would be that her son would come back from the dead. Murch adds that if the distraught woman’s son could return, he would come back to remind Americans of the importance of the war. In the fairy tale logic of horror, the American war dead from Iraq do begin to return, not to feast on the living or to praise American foreign policy, but to “vote for anyone who will end this war.” Commenting on the Bush administration’s ban on photographs of body bags, dead soldiers, and even soldiers’ funerals, Dante has flag-draped coffins that burst open to reveal the walking undead veterans. The left-leaning

Village Voice

described “Homecoming” as “easily the most important political film of the Bush II era.”

57

Zombie films have also proved adept at satirizing a number of issues in American society more generally. Danny Boyle’s

28 Days Later

portrayed its “running zombies” as uncontrollable mobs and the infection as both an AIDS-like plague and a kind of terrorist threat.

Zombies of Mass Destruction

, as is clear from the title, references the war on terror and the Iraq War, portraying the inhabitants of a small island becoming zombified and turning on their neighbors. Director Kevin Hamedani shows us the action partially through the experience of an Iranian-American woman who local residents believe has ignited the zombie apocalypse as part of a terrorist attack. She is tortured, Abu Ghraib-style, by one of her hysterically paranoid neighbors.

The zombies of popular culture are situated in the trajectory of American history. Undead revenants from popular culture rather than monsters of folk belief, the zombie symbolizes for many Americans the current state of their own society or its eventual direction. The hopelessness of the genre, with its images of civilization’s dissolution, and human beings cannibalizing one another, captures a sentiment that, in retrospect, has been a theme in American life since the 1960s. The forced optimism of the Reagan years, the current glorification of the post-World War II generation (“the greatest generation”), and the generalized nostalgia for earlier eras points to profound unease about current American society and its place in global history. America after 9/11, a place that now must experience history with the rest of the world, is a veritable buffet for the hungry undead. They’re not just coming for Barbara. They’re coming for us all.

The Hilton sisters. Photofest publicity poster. Courtesy of Photofest.

Image of Elsa Lanchester as the Bride of Frankenstein. Courtesy of Photofest.

Boris Karloff as Frankenstein’s Monster. Courtesy of Photofest.

LeBron James and Gisele. Cover of

Vogue

(April 2008).

King Kong

movie poster with Fay Wray. Courtesy of Photofest.

Dracula Takes a Bite Out of Mina Harker. Courtesy of Photofest.

The Thing from Another Worl

d poster. Courtesy of Photofest.

Scene from

Invasion of the Body Snatchers

. Courtesy of Photofest.

Jamie Lee Curtis—On the Set of

Halloween

. Courtesy of Photofest.

The Exorcist

movie poster. Courtesy of Photofest.

Alien 3

by David Fincher. Courtesy of Photofest.

Halloween

poster. Courtesy of Photofest.

Dracula from Hammer. Courtesy of Photofest.

Night of the Living Dead

poster. Courtesy of Photofest.

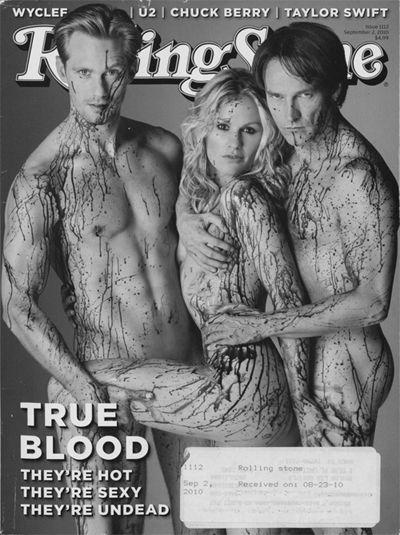

True Blood

cast. Cover of

Rolling Stone

. September 2, 2010, print issue.

Terminator/Frankenstein juxtaposition. Courtesy of Photofest.

—

Bauhaus

—

Bela Lugosi,

Dracula

I

n 1994 Freddy Krueger invaded America’s nightmares once again. Ten years after the trash-talking slasher first entered his victims’ dreams,

New Nightmare

reimagined the Elm Street mythology in a radical fashion. Director Wes Craven’s monster escapes the realm of imagination and stalks Heather Langenkamp and Robert Englund, the actors who portrayed the final girl and Freddy himself in the first film. He even stalks his creator, Craven himself.

1

New Nightmare

was the first of the Elm Street films that Craven, a former literature and philosophy professor, directed since the series debut in 1984. In this revisionist reading of his own work, Craven proposes that Freddy was an actual being, a dream demon, whose power had been contained by the telling of stories about him (the first seven films in the series). Now that the character had dimmed in popularity, he was no longer bound by the narrative and freed himself from the prison of the script. This ingenious story makes the monster into something even more dreadful than the horribly burned child-killer who returns from the grave with a razor-fingered glove. He becomes an archetypal monster with many faces, appearing in different times and epochs and wearing many masks.

2

New Nightmare

’s use of metanarrative, narrative about narrative that implicates the audience in the story being told, proved unsuccessful with that very audience. Two years later, America seemed a bit more prepared for the postmodern monster. Craven’s runaway hit

Scream

took the basic premise of

Halloween

and deconstructed it. The film contained numerous references to other horror films, and the killers themselves are two slasher film aficionados whose fascination with the genre structures their mayhem. Audiences fell in love with

Scream

’s aesthetic, mirroring as it did other pop culture styles present in everything from MTV to

The Simpsons

and addressing itself to the increasingly blurred lines of media representation and reality. Audiences may have understood Craven’s efforts better than some critics, one of whom rather laughably described

Scream

as “highly derivative.”

3