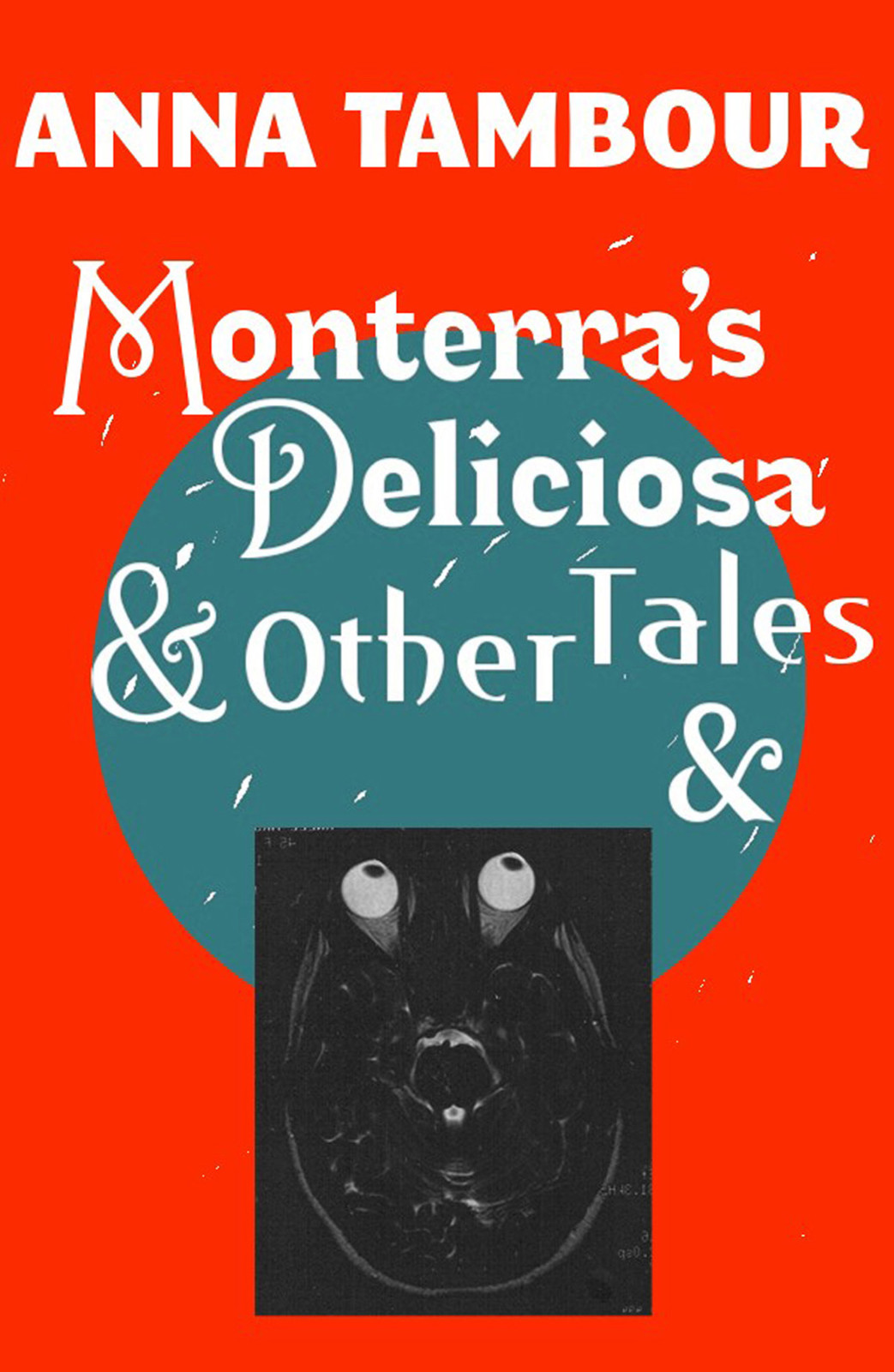

Monterra's Deliciosa & Other Tales &

Read Monterra's Deliciosa & Other Tales & Online

Authors: Anna Tambour

Tags: #Fiction, #Short Stories (Single Author), #Literary Collections, #General

- Introduction

- Klokwerk's Heart

- The Eel

- The Curse of Hyperica

- Temptation of the Seven Scientists

- The Afterlife at Seahorse Drive

- The It and the Ecstasy

- Travels with Robert Louis Stevenson in the Cévennes

- The Chosen

- Stargazing

- Kidnapped!

- The Helford Deal

- Me-Too

- Crumpled Sheets and Death-Fluffies

- Sweat, Joy, and Thunderation

- Valley of the Sugars of Salt

- Catechismic Chaos

- Dr. Babiram's Potentials

- Exhibition

- The Refloat of D'Urbe Isle

- The Apple

- The Rest Cure

- The Magic Lino

- Call me Omniscient

- Bluebird Pie

- Picking Blueberries

- The Wages of Food-Play

- Öm

- The Ocean in Kansas

- Monterra's Deliciosa

- Literary Titan, Asher E. (huh?) Treat

- Pearls

- Publishing history

- Roos at the beach

- The Arms of Love and Death

- Lorimer's Next

- Cooks' Tricks Nix Sticks

- Pococurante

- The Onuspedia

- The Purloined Tome

- Wodehouse, Snails, and Dramatic Interest

- About the author

Monterra's Deliciosa

& Other Tales &

Anna Tambour

Monterra's Deliciosa

& Other Tales &

More than 30 stories and poems from an author described by SF Site as "one of the most delightful, original, and varied new writers on hand".

A landmark collection of short fiction from a dazzling new talent. The stories range from sharp satire, through fairytale and tall tale, science fiction and fantasy, to passionate mainstream studies of life in modern Australia. Reading these stories, you quickly come to realise that you will be surprised, and surprised again.

Follow the seven scientists in search of a great theory, naturally enough (and it does seem natural in this author's hands) in a forest teeming with great theories; follow Werner, who creates intricate living machines while Gretina knits for the needy, a quite extraordinary love story where the everyday is always juxtaposed with the fantastic and real magic is never far from the surface. Flip from the whimsy of Robert Louis Stevenson's travels through the Cévennes as told by his donkey, to fears and a distorted sense of scale seen as only a child can see. Journey from a tough Australian farming community to a seaside retirement colony, to a 1970s alternative community, to rural Iowa and beyond.

Prepared to be unprepared. Be careful in here: there is an author at play within these pages. Anna Tambour is having fun with you and she has a wicked sense of humour.

Includes 17,000 words of bonus material.

Chosen in two categories (Collection and Novelette) in the Locus 2003 Recommended Reading List.

Published by infinity plus at Smashwords

www.infinityplus.co.uk/books

Follow @ipebooks on Twitter

© Anna Tambour 2003, 2011

cover © Anna Tambour

ISBN: 9781301050291

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy.

Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means, mechanical, electronic, or otherwise, without first obtaining the permission of the copyright holder.

Shorter edition first published by Prime Books September 2003

Wildside Press(September 1, 2003) Hardcover and Paperback

The moral right of Anna Tambour to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

Electronic Version by Baen Books

Introduction

Somewhere deep in the Australian bush, surrounded by an extended family of cockatiels and koalas, wombats, kangaroos and fruit bats, there lives an author who writes miraculous little fabulations, each crammed with invention and insight and humour and above all a quirky

difference

that makes them quite unlike the work of any other. She tends these creations, breathes life into each one and lets them loose into a far-too-often-uncaring world.

These little gems, for all their vitality, cannot exist in a vacuum. Publishing is an industry, and a competitive one at that. In my own country alone (albeit at the opposite end of the world to the one where these stories are created), tens of thousands of new books are published every year; among them, so many talented voices are stifled, drowned out in the clamour. These voices need nurturing, they need attention — particularly the special ones, like that of our whimsical outback author.

Fortunately, Anna Tambour is starting to get that attention, quite deservedly so, and she is certain to get much more. Even in a crowded, clamorous throng, some voices stand out above the others — the loudest, for sure, but also those that are different, the ones with wit and wisdom, the ones that dare to surprise.

Anna Tambour's is one of the voices that stands out, and for all the best reasons.

~

I talked my way into writing the foreword to this volume on the strength of a handful of off-beat and quite brilliant stories Anna submitted to me for the

infinity plus

website. Now, having read all the contents of this collection, I have been struck over and over by a series of triumphs.

Much of the time, I have read with a smile on my face, not only for the wit these stories contain, but for the sheer audacity of the author. In many cases, I start reading and then find myself wondering how on earth she expects to get away with this premise or that. Describe them to a friend, as I did recently, and they often sound, to put it bluntly, quite silly. There's one about Robert Louis Stevenson's travels through the Cévennes which is told by his donkey; another about a magical piece of linoleum; and another which is a potted history of food, and God's distaste for our tastes, not forgetting His secret garden atop Everest... Yet, just as that how-could-she-try-this thought strikes, so it is dismissed by a twist, a turn, a feint, and you find yourself swallowed up in whichever strange conceit is currently being explored.

There is far too much in this collection to make it a worthwhile exercise to itemise its contents here, but I cannot go without dwelling on the many highlights.

Many of the stories contained here take the form of the traditional fairytale, although they are re-cast in a way that is distinctly Tambourian. "Temptation of the Seven Scientists" tells the stories of seven scientists in search of a Great Theory — naturally enough (and it does seem natural, in this author's hands), in a forest teeming with Great Theories. This tale charms with its sheer up-frontness, and its zestful toying with the reader. In "Klokwerk's Heart" Werner creates intricate living machines while Gretina knits for the needy. On the surface, this is quite an extraordinary love story, but in this author's work the everyday is always juxtaposed with the fantastic and real magic is never far from the surface, deepening and questioning.

Quickly, you learn to expect to be surprised and then suprised again by these stories. "Crumpled Sheets and Death-Fluffies" flips and flops from a heartfelt portrait of a writer's existence, to intense horror and then wicked black humour. Roald Dahl: meet Anna Tambour. "The Apple" is a beautiful vignette taking the reader right back to what it is like to be a small child: the fears, the distorted sense of scale of what matters and what does not, again with that dark, dark sense of fun at play.

Anna writes about the natural world as only one with deep knowledge and understanding can do. "The Chosen" is a wonderful parable of human intervention in nature, as great multitudes worship the gods of unnatural selection and assisted migration, and the strong prepare to inherit the earth. "Valley of the Sugars of Salt" sets out as the straightforward tale of a man, successful in business but not in marriage, retreating to the country to grow gourmet and largely forgotten fruit. Inevitably, the story bucks and surprises and the ground shifts drastically beneath the reader as the orchard becomes something of a cooperative venture.

Some of these stories are almost straight pieces of fiction, but the author can never quite resist the opportunity to dig and twist, to subvert and surprise, to confound any expectations we might foolishly have. "The Afterlife at Seahorse Drive" is about as close to mainstream as we get, a stunning evocation of the upheaval of a big move into retirement, from a tough Australian farming community to an embryonic seaside idyll. "The Rest Cure" shows that our author can do moody and disturbingly intense, too, but always there comes that point where everything begins to shift. And in "Call me Omniscient", well ... how many authors would dare to tell a story from the viewpoint of a story-telling mode: the omniscient? You just can't do this sort of thing, and it certainly shouldn't work as well as it does in this quite ingenious and audacious story. "Picking Blueberries" is one of my absolute favourites, a superb portrait of an alternative community in the early 1970s, told with a child's-eye simplicity by a young resident. There's a novel here: it really is good.

The title piece and the longest story in the book, "Monterra's Deliciosa", is another true highlight, the story of a boy born into an Iowa farming family who is destined for an entirely different kind of life in which everyone makes the reckoning of what price is worth paying for the life you want to lead.

There: you should be prepared now. Prepared to be unprepared. Be careful in here. There is an author at play within these pages. Anna Tambour is having fun with you and she has a wicked sense of humour.

You have been warned.

Keith Brooke

Brightlingsea, May 2003

Klokwerk's Heart

- 1 -

Through the high window, a shaft of sharp summer evening sun fell into the silent room, pierced the openings in the skull, and threw its light out the other side to paint on the white wall the stark silhouette, crouching as always, of the pterodactyl. Its wide-open amused eyes and its incongruous smile always disturbed Werner, but not as much as the Volkswagen-sized raptor's towering companion, the tyrannosaur. Together, their forms on the wall resembled nothing so much as some malevolent master walking his dog on a rainy night.

It was 7:15 p.m., one hour and fifteen minutes into Werner's first round. All visitors had been shooed out the doors hours ago. Werner averted his eyes from master and dog, and scuttled on his soft-soled shoes through the faintest miasma of dust, out the doorway on the far side, to the small low-ceilinged room beyond. His breath came out in a small exhalation, but his shoulders were still curved in tension like the back of a wooden chair.

Holding his breath again without noticing the lack of oxygen, he stopped and wiped his hands on his uniform, startling himself as a thumb caught in his key bouquet, bringing a small but harsh jangle into the silence. He didn't look at his watch.

"Klokwerk," the other guards called him. Always exactly on time in his rounds, meticulous in every bit of his reporting. In twenty years at the museum, there had rarely been anything to report. The after-hours visitors had only ever been the odd wayward pigeons and occasional mouse and rat plagues in the kitchen. Both the flying and the scurrying invasions were always quickly ended by poisoning. As for rats gnawing the many life-like stuffed specimens, the reek of naphtha was so strong on several floors that many guards who thought of trying for this easy museum stint discarded the idea after a brief reconnaissance.

Across the box-hedged public square: the great art museum, the building of thrills. Only two years ago two alert public servants had wrangled down a lithely photogenic female would-be heister, and all the young ambitious guards now roamed those halls, all dreaming of the opportunity to catch their own thief, literally hanging from the skylight.

Here in the natural-history museum, though, no crowds of tourists ever mobbed the entrance. No plans were made to steal the ancient armadillo the size of a pony, the stuffed walrus watching the little boar so benignly for, what, a hundred years? The butterflies that gazed back at you from their wings, even the marvellous crystals in the Mineral Hall. None of them was worth what a square of canvas with paint could bring. Thus only the dregs of unambitious night guards ever took up posts in this haven of perpetual boredom. The halls reverberated with children's voices every weekend, but after the doors were closed for the night, only the barest skeleton of night-shift staff roamed the huge shadowy building, and only in the most meticulously unimaginative, patterned, and clockwork way.

~

Werner unbuttoned his guard jacket, then his blue regulation shirt. He spread the shirt open in a neat V down to his waist. Underneath, he wore an old but neatly patched vest, covered with a patchwork of idiosyncratic pockets, each closed with its own just-as-individual fastening.

He'd found the vest years ago in one of those shops that sells knives with deer-horn handles, rabbit's-foot picnic forks, skinning blades of lead-hued steel, whistles cast in the shapes of hounds. The shop was on his way to work, and as he walked the same route every day, by the second day that he noticed the vest in the window, he was burning with desire. He had no interest in the other things, or even in learning what the vest was for, but he knew it was right for him. It was the night when shops stayed open late, so he pushed open the bell-jangling door and bought the thing as soon as it was in his hands, without blinking at the price.

Since then, there had rarely been a day he had not worn it. Of course, this was the first time he had worn the vest somewhere other than at the big round table at home. The table where they companionably ate their meals, especially the feast Gretina made for their nightly 4 a.m. dinner. Never a can opened or a delicatessen visited would be good enough for her Werner, according to Gretina. Luscious liver soup, home-made blood sausage, her incomparable hasenpfeffer (spicy enough that they sneezed), spaetzle that were heavy and chewy as a man likes, cherry dumplings to make them both imagine a countryside that they had only ever visited in their imaginations. Everything was worth licking the plate, and Gretina made sure that they both did. "It makes you wild, Werner," she giggled, as he was always the most gentle, mild-mannered man.

After their dinner, when he had washed and wiped the dishes, and she had swept up any errant crumbs and removed the snowy tablecloth to replace it with green baize, they both took their projects to the table for their after-dinner day-dawning enjoyment, the final preparation being Werner taking his vest out of its drawer in the heavy wooden many-drawered cabinet and, with a muffled clank, putting it on.

Once Werner tried to calculate how many kilometres of wool Gretina had knitted, but lost count at her twelfth enthusiastic project. Not that he cared, for her clicking needles were the sound of home to him, and the look of satisfaction as she finished each piece was like the taste of her cherry dumplings to his soul.

And the projects? Too many to remember. Knitted scarves for Africans (did it get cold there? He wondered), hats for children who had undergone radiation therapy, blankets for refugees; now she was in the middle of a long project with lots and lots of little things that looked like teapot cosies, but were jackets for penguins recovering from oil spill injury.

As her needles clicked, she watched Werner, seated across the grass-green circle from her. He worked with his tiny tools, dozens of them, to make incomprehensible objects. All small, smaller than her hand; all like nothing she had ever seen. They whirred, they pulsed, they pumped when he stuck tiny tubes in them. They crawled along the table till they fell into her lap as laughter filled the room. Silvery from Gretina, a lark's warble with delicate beauty to the trill, a sharp contrast to her plain dumpy features. A shy, quiet laugh from Werner, his thin face with its pockmarks suffused by the joy that love gives.

No two machines that Werner made looked alike. Try as he would, he could never convince Gretina that they were all, in fact, variations on a theme—machines of life.

Werner, on the other hand, had no trouble recognising a theme—well, two, really—in Gretina's projects: compassion for someone somewhere, and stars.

In everything she knitted, she placed stars somewhere in the pattern—in the design of the stitches or with contrasting colour, she made sure that there was at least one star in every item she made.

Why stars, he asked her once.

Her lips pursed in concentration. "I don't remember exactly to explain. A story from my mother. Stars shine upon you whether you see them or not... Something like that." She smiled a bit sheepishly. "And a penguin wearing a star seems happier."

The reason didn't make any sense to Werner, but the happiness did.

As to the compassion, they were both sad not to have had children. Gretina was allergic to cat and dog fur, and caged birds made them both shudder. So her excess love had to go somewhere. And it went into her busy needles knitting, knitting, while she watched her husband with awe as he cut steel with his precision drill with a smooth sound like slicing cheese, and a curl coming off crisp and pure as the peel of an apple.

When he had finished a new machine and assembled it, the table was cleared of all encumbrances so it could move at will, dancing for her delight—and for his in watching her. He loved to put a whole population of machines on the table at once, and make them all act in their selfish ways, bumping blindly into one another, or singly enjoying themselves in what looked like a dance to an internal tune. Gretina laughed and clapped her hands softly, the knitting lying forgotten in her lap.

At 9:45 a.m. precisely, she put away her wool. Werner carefully cleaned up his work area on the table and floor, and picked up and put away his tools, along with the latest mechanical creature in the making.

At 10 a.m. precisely, the kettle sang, and they together made, ate, and cleaned up their supper.

They never spoke much. For them, companionship needed no chatter.

At 11 a.m., the small old-fashioned apartment was dark, with heavy curtains pulled to keep out the light coming through the deep, double-glazed windows. The only sounds inside were those of two quiet people giving and getting enormous joy.

~

Werner felt fresh, as he always did at this hour, early in his night's work. But at no other time except the first time he had coffee with Gretina five years ago had he been so nervous.

A burp almost escaped, but he swallowed it, even though he was alone. He tasted cinnamon, apples, and bile.

He glanced at the light falling from the high window, and reached into his vest. Out of four pockets, he drew the makings for a tool and attachment, which he assembled in a moment. He was in a corner away from either doorway. He bent his knees to crouch beside the hundred-year-old waist-high cabinet. In another moment, he had scuttled underneath it.

With his tiny drill, he made one small entry hole; then a larger hole with a ream bit. He fished into another pocket and pulled out a flexible grabber with a lit viewing panel attached. With the skill of a surgeon, he manipulated his instruments, extracted an object from the case, placed it in a vest pocket with a bone button closure, then pulled out a tiny vacuum that whirred like a bumblebee for a few seconds. Then he poked, pulled, and prodded through the hole till he was satisfied—and finally sealed the hole with a pre-made plug that he pulled from yet another pocket.

Tools all pocketed, he crawled out from underneath the cabinet, stood and carefully rearranged his clothes to their customary neatness, smoothed his thin hair with both hands, and left the room a trifle faster than his normal pace.

~

By the time his 10 p.m. lunch break came around, Werner's outer composure had been restored with such completeness that he looked like he was asking his fellow guards to tease him for being the most boring and even-tempered person in the whole of the city. "Tick, tock," Olag mumbled through a mouth full of sausage, as Werner, to the dot of the minute, entered the small guards' room. Werner would have to put up with this rostered companion for the entire break, as he needed to get off his feet, but Olag was no worse than the others.

Werner smiled, never outwardly riled. He had always been ridiculed; in school, his pimples had kept him from wanting to attend even the polytechnic. Too much to do with people.

Being a night guard suited him. And Gretina was more than any man could wish for, especially such as him. So Werner didn't react as Olag continued to make jokes at his expense. Werner neatly unfolded his lunch, and ate it just as neatly. He followed it with his customary two pills and a glass of water. His face was calm, but his normal thoughts at this time, of new machines constructed first in his head, were totally disrupted.

Instead, his stomach tumbled over itself. His mouth filled with saliva, then dried out. The tips of his ears (if Olag had been observing, he would have treasured the picture) glowed red, then white, as Werner's emotions threw his blood around his body as a cat throws a mouse around a room.

He was feeling the most delirious thrill of joy, mixed with an agony of anticipation, and spiked with that most potent spice: fear.

The hours passed, and he left soundlessly in the meaningless noise of camaraderie as the guards changed shifts. Their steps faded away, a small car bleated, and then he was alone again, on the way home. He liked this walk, enjoying the quiet of monumental buildings all to himself, vast doorways, tall naked men and bare-breasted ladies gleaming whitely in the street lights as they stood with the weight of second stories or just pensive thoughts on their noble brows.

On the parliament building, a giant globe looked like another planet, half dark, half lit. It was guarded, or maybe just surrounded, by four giant eagles, with another eagle, even more majestic, perched on top. Werner often smiled unconsciously as he approached parliament house; he could admire the eagle without having to look down at the pavement, because he knew how many steps he needed to take before he reached the curb.

At more human height, Werner enjoyed the small surprises that the architecture of his own old neighbourhood presented: lizards carved around an entrance; a man on a horse, caged against pigeons, prancing forever atop a doorway at the corner of his own street; a bronze dog's-paw door handle for an old pet shop that he could never have the pleasure of entering.

At 2:30 a.m., he stood between the larger than life-size stone man and woman who gazed perpetually towards each other as they guarded the entrance to his apartment house. As he always had, for a fleeting second he stopped and admired, with a look one way and then the other, the calm dignity of the man and the woman before he needed his whole body to push open the heavy glass and oak door.

Up he walked, three flights on the worn marble steps, to apartment 3C, where the door was already open, a discreetly welcoming glow shining out, blocked only by—to Werner's thinking—the most beautiful woman in the world.

Gretina took his old green boiled-wool coat and hung it on the coat rack, then returned to her husband, still standing in the doorway, for their accustomed long homecoming embrace.

Then she led him by the hand to the table, where she sat him down as usual to take off his shoes and socks, and then the rest of his clothes, preparatory to leading him to his bath. Later, relaxed and clean, he would come back in his home clothes to sit at the table, where Gretina would serve them both their 4 a.m. dinner.

But he pulled out from her grasp and skittered away to stand in the middle of the room under the softly lit hanging lamp. And he giggled!

He held up his hand, first putting a finger to his lips for silence, then an open palm for "stay where you are." But Gretina was rooted to her spot, totally dumbfounded.