Moon Called (15 page)

Authors: Andre Norton

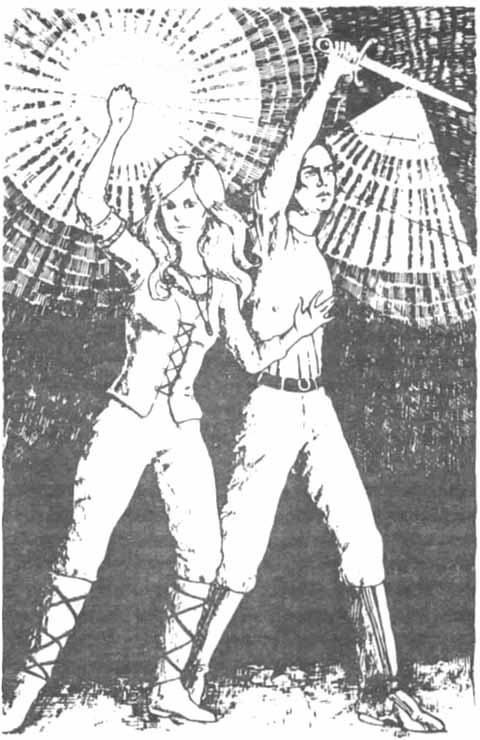

Holding the chain firmly by its free end, she swung the jewel back and forth, and then whirled it out towards the Dark Lord.

Those flames which encircled him, were fed by his knowledge, his spirit, touched the jewel. There followed a flare of such brilliance that Thora cried out, even though she had been shading her eyes with her other hand. Lur's Light drew upon that flare. So fed, it in turn pierced and struck!

The flames roared into an unholy fire, seeming to draw substance from the light of the sword. They hid the Dark Lord utterly by a wall which was first a sullen red, and then slowly lightened, to the yellow of the full sun—finally to the pure light of the sword beam, or of her own gem.

That which had been aimed had returned, a thousand-fold.

The column of flame, now purely white, began to shrink in upon itself, growing smaller

and smaller. Thora waited to see the Dark Lord appear once again. But—

No one stood there secure in pride and power as the flames receded farther and farther. Was he kneeling? No, already the fire had shrunk—was he—?

There was nothing. Where the Dark Lord had wrought with the full command of the forces he could summon—there was nothing! Even the drummer who had lain at his feet was also gone. The flames in turn dwindled, died.

Now the two men left from the enemy force moved feebly, raised their heads. But there was no true life in them. They were as husks driven by the wind, allowed to fall where they might. Thora heard the other sounds, turned her head a fraction. Those who had been herded forward by the second crawler were falling—or blundering straight into the walls of the boxes, as if rendered mindless. The second drummer crashed forward—his instrument splintering under his body.

She believed she understood. In the final drawing-in of power the Dark Lord had pulled upon not only his own strength, but upon all the inner life of those who followed him. What were left now were bodies without spirit cores, bodies which were already beginning to drop to the floor, even the life of the flesh departing when there was no longer a true essence to hold it intact.

A vast weariness struck at her. Perhaps the Dark Lord had not made of her one of these husks, but he had pried and picked at her spirit. While, in the end, she had given all she had to give when she had used the jewel. Out of her, also had flown power, and, as Thora slipped down the side of the boxes against which she had leaned, she wondered dazedly if she were about to follow the Enemy into the final darkness.

That did not yet close about her. Makil and Kort leaped from the back of the monster, going forward into the battle field to survey those still remaining. Now the girl witnessed the opening of a lid pushed upward where the valley man and the hound had ridden into battle. Through that a furred body pulled itself.

Then, with a light leap, Tarkin also dismounted. But the furred one had no eyes for the site ahead. Instead she came straight to Thora, her clawed hands touching the girl gently, first on forehead and then over her heart.

Tarkin caught up the chain of the gem which was still between Thora's fingers, drew the silver length towards them. She touched the jewel itself with care, as if she expected to find it subtly changed in some manner, and then nodded as if reassured.

Moving quickly she laid the jewel on Thora's breast, just above the mark which the Lady had set upon the girl so long ago. There was no

blazing heat in the jewel to wound and burn, but rather it was cool, as if Tarkin had dripped down upon her fevered flesh purest spring water.

The furred one again touched her gently. “Rest, sister—we have done much, but there is still more to do.”

As if that were an order which she could not disobey, Thora closed her eyes, and then indeed swung into a darkness which was welcoming and in no way evil.

But it was a darkness in which there was life and movement—although none of it touched her. She was as one, who blind, still walked with sure, swift steps along a road where she knew she could not stumble and which would lead her straight to that which she had always sought.

Only she did not walk that road alone. There were many others, she could not see—carrying with them a sense of purpose and of need. So that Thora was sure that each had duty to perform. There was a feeling of time which—which was the road itself! That which lay behind ever gave birth to what lay still before. Far back there had been deeds done which were like unto the unopened buds of the flowers of the furred ones; now those deeds must open, then provide the final fruit.

Thora only trod that road for a heartbeat or so, but she knew it for the stream of true life, and that she was indeed a part of a weaving

which had begun long before and was still to have its pattern finally set far, far ahead. The thread which was Thora had been pulled in and out—forming parts of many designs in passing—designs this Thora could not remember, for it was not the part of the thread to remember—unless that was allowed when one reached the destined end of the weaving.

She was now Thora, but she had been called by other names, and lived in different ways. All of those had had meaning and were of the power—though it might be a different kind of power. She had a flash of seeing—a Thora who went armed and who fought the Enemy—not a red-cloaked one—but of the same breed with weapons—who hurried with a fearful and pressing purpose to duty in a place where much must be hidden against another day—a Thora who had known during that journey the sharp outweaving of death—and then—

But that insight was only a flash and quickly gone. Yes, that which rested during the outweave could not be remembered. Perhaps the thread of those rested mindless and quiescent until it was time to help form a new design.

There was the scent of flowers—white bells of flowers. One danced among those drawing in strength—letting it flow out again as a balm and boon to others—

Thora felt a soft down against her cheek. She opened her eyes. Her head rested in

Tarkin's lap, there was the edge of a cup set to her lips, and the furred one was so urging her to drink. The red of the eyes above her was softly glowing—like the small flame of a trail side fire which was in its way a protection against all which might crawl in the dark.

“Drink, sister. This is now the time to be gone.”

She felt the rough caress of Kort's tongue against the hand which rested at her side. The hound's bright eyes were watching her. Now he whined as she lifted that hand to lay upon his head. She drank and the liquid was sharp, aromatic. As Thora swallowed and felt it warm her, she knew also a return of strength so that she lifted herself out of Tarkin's hold to look around.

This was not the edge of the battlefield where she had fallen. They were in a wider, open space and before them on the wall was the outline of a door—a large door. There Martan and Eban were busied. The girl caught a glimpse of one of the same kind of wheels for locking as she had found in the tunnel leading to the place of storage—save that the door this one controlled was far larger.

There were the two crawling machines, also. Those two which must have brought the battle to the Red Cloak. Sitting perched on them by the open doors in the tops were Malkin and the male each licking from blood vials. As Thora moved Makil came quickly to her.

The Weapon of Lur was back in its sheath, its hilt showing above his shoulder. He was smiling, and there was a softening in his expression which she had not seen before.

“That was well done, Chosen,” he said.

What was well done? For a moment Thora was confused. Then she understood and her hand sought her jewel.

“Better than that, even, Chosen. You brought us both the key and the lock, and now we shall see what comes of knowledge.”

Thora shook her head— “I do not understand—” she began.

His smile grew wider. “Ask this sister,” he nodded to Tarkin, “for indeed it was she who had the answers for us—”

15

This time Kort did not lead the way across the open land, rather it was Makil who walked at a steady pace, swinging the unsheathed sword above the quick growing grass. And sometimes from that grass, a stone, or even a spot of bare earth, there would shoot a spark of dull red—sullenly answering the Weapon of Lur, marking the path earlier taken by the forces of the Dark. He would rest at times, returning to ride with the others on those lumbering crawlers awakened from centuries old sleep. Then Borkin took his place, using the wand.

Thora rode reluctantly. She did not share the valley men's triumph at the new life of these massive things of metal. To her they

were dangerous to her own kind and she placed no trust in them.

However, it had not been the men who had brought them to life. She discovered that when they began that journey and Martan spilled out eagerly all which had happened after she had run to Kort's call. Perhaps the machines had been made by people distantly akin to them, but it was the furred ones who actually controlled them.

That was almost the hardest to understand of all that had happened. Between such as Tarkin and these huge crawlers now trundling along Thora could see no kinship. Surely those who lived in the flower-entwined wood, and made magic akin to what she knew, could not be tied to this metal bearing—to her—the scent of dusty death. Her world was not the world of the storage place.

Surely it must have been men who had fashioned these things—men akin to that sentry they had first found dead. Martan, who gloried in his sky-conquering wings, he could be of the same distant blood. Why was not Martan then, or Eban, or even Borkin, the one to sit in that contained space where there was a board of many lights to be fingered—fingers used instead of busy and agile claws?

Yet it was Tarkin and Malkin who alternated in that cup of a seat there—by its size surely fashioned only for one of their race. And it was the male of their kind who guided

the second of the moving boxes.

Thora could not believe that the furred ones had built these. She mulled over that mystery, as she held on firmly with both hands, set her teeth, gave care to maintaining her place on that tipping, rocking surface. Martan lay belly down on the second machine, his head hanging over the open door, his attention all for the actions of the driver. Eban was beside him on that second crawler, but appeared less concerned with how they were getting there, more with where they were going.

They crushed and battered a way onward. Nothing seemed able to deter the passing of these creeping fortresses of metal. They crunched earth, even small trees, under their treads—even as the one had overridden that monster of the Red Cloak.

Sometimes, as she so jolted along, Thora felt as if she traveled in a dream, even though they halted at intervals and she ate and drank with the others. She was still weakened by her struggle with the Dark Lord. Only the waxing moon overhead tied her to what she could understand. Here the Lady could be reached. They were the hunters, and that which Makil and Borkin could control pointed the path.

At the midpoint of the night they halted to camp. Thora climbed stiffly down from her perch, glad to stand on honest ground again. Borkin and Makil established the protection area, but not about the two crawlers—seemingly

careful as they wrought so to avoid any contact with the machines. It was almost as if some half-forgotten enmity lay between the metal monsters and their own things of power.

She asked no questions, determined that she would keep herself aloof from what she distrusted so. This was not of the Lady—But then the valley men used the wings, thus it followed they were excited, pleased by the crawlers. This enthusiasm set them even farther apart from what she deemed right and natural.

Tarkin came to sit beside her. The furred one flexed the fingerclaws of both hands as if they had stiffened at their task. Then she dug into her food pouch and ate with noticeable appetite. It was as if—though to the eye she had only sat within that cubicle at the top of the machines and moved her fingers—she had performed some heavy, exhausting labor. Now she hissed a sigh, stretching her arms wide, straightening her back. Thora asked the questions which she would not voice to the men:

“Tarkin—what power do you use?”

The furred one's eyes were heavy lidded, they did not blaze—though the light in them was warm and steady.

“We have remembered—”

“Remembered what?”

“What was of old and who we are and why we were once born—through forces which were forgotten in the Change. We

were

born for a purpose, sister—though, in the long

years since, we have changed also, becoming in many ways different from what we once were. Still in us there lay a deep memory asleep and it was wakened—perhaps by the power of that demon drumming. A forgotten place in our minds opened—” she shook her head slowly. “It is true that with us sounds have very great powers.”

Thora remembered that pain-giving sound which Malkin had used to win their battle with the rats, and she could believe that. Also there was the dancing song. Yes, the furred ones had their own form of power—even as she her moon-call gem, Makil his sword, and Borkin that wand.

“So, suddenly remembering, we went to the task for which we were first intended, we brought out the machines which only we could move. In the Days Before there must have been some reason why we were the ones—” she rubbed her claws across her forehead— “but memory so deeply buried can be faulty. Perhaps my people never even knew why this task must be theirs. We were never like you—but that you already know. We spring from a far different seed, but we were given skills so we were used—”

“Used?” Thora repeated, that word had a sour taste in her mouth. To use intelligent life—that was of the Shadow, not of the Lady's clear way.

“Used!” Tarkin was firm. “It was the

Change which freed us, that we might learn what we ourselves chose to be, to grasp our own power. Still there was born into us—and that we could not forget—a need to be close to man—such as those of the valley. This bond became a different kind, perhaps, than it was intended—rather one of bloodsharing. Neither of us could understand just why we could and did make such a choice—why most of us had a longing to be so joined. I think it was another thing planned carefully by those who brought about our existence, so that in time of danger, the blood-bound could be ready to face danger as a single entity, one need, one mind— Save—” Now she looked directly at Thora, “when you came there was a new thing—a meeting between us which was not to be bound with blood. Perhaps this is a different pattern—a new one— But there is always a pattern.”

Thora nodded. “Always a pattern,” she agreed. “What is the true purpose of these things which you guide so?”

“They are weapons—such weapons as have not been seen—even in the Days Before, I believe. I think they were new made then, hidden for some reason—to be used only in some last battle. Just as we were raised and trained for that same warfare. They can and do carry death in a new and dreadful form, control powers which are not the kind we know—for they are neither of the light nor the dark, do

not answer to words of ceremony, but can serve only those trained in their secrets. Now we take them to the Dark and with them,” she spread her clawfingers wide, “we shall render such an accounting as perhaps shall banish the shadow. Maybe not forever, for that I believe cannot be done, but at least drive it hence for a space—”

Thora drew a deep breath. This was all like some wild trader legend. Still there stood the crawlers, and she had watched Tarkin make that mighty bulk answer to her as Thora's own knife and spear answered to the muscles of her body.

Surely this was an odd weaving, yet she could see how the strands had been gathered together—her discovery of Malkin—the finding of the underground storage place—then her journey to the valley—her own first brush with the Red Cloaks—her coming to the place of the furred ones and her meeting with Tarkin. Then came all the rest—the return for the treasures of the Days Before, the drums (which Tarkin believed reawakened memories) to teach the furred ones their once purpose in life— Yes, all was so well woven she could believe that this was how it was meant to be. What was the final design? The defeat of the Dark Ones with these forgotten weapons? It would seem that the furred ones and the valley men were united upon that. And she was still a part of it all whether she chose or not.

Awakening they moved boldly by day, crunching their way onward. Even in the sun, both sword and wand could mark for them the path along which the vanquished Dark Ones had come. Now Kort took to coursing ahead, adding his own senses to their seeking.

They had been two nights and a day on their way when, on the dawn of the second day, they saw ahead the rise of a dark mound, in the grey light that was familiar to Thora. This indeed was that place to which the silver footprints of her vision had led her.

The crawlers came to a stop and those riding leaped down. Then doors opened in the sides of the huge machines and they pushed inside —even Kort, coming at Thora's call, though he growled uneasily.

Within was a space as large as a small room, with stools fastened to the floor set at intervals. Before each of those wide murky plates on the wall. Thora seated herself cautiously, Kort on the floor beside her.

From somewhere came a bell note and that plate before her cleared into a window. She looked out at the dark side of that fortress.

Below each window a ledge jutted out from the wall, forming a half table above the knees of those seated there. On that surface lights began to play, shining faintly out of small pits the size and shape of a finger tip.

“Weapons controls?” Makil asked, not as if he were expecting any answer but rather

musing on his own guess.

Lights as weapons? Thora could not see the connection—but then all of this was alien. She kept her hands firmly in her lap, resting by instinct over the moon gem.

That remained cold, lifeless. Now there was the prick of fear in her. But she must not allow that—must instead use her trained power to combat it. What—what if the Lady did not reach here? Thora was more lost within this rumbling box than she could be inside that threatening fortress ahead—for she had no control over any force now.

The girl shivered, longing to batter her way out of the crawler, but she was not even sure her legs would support her to the door. Her strength seemed draining along with her confidence.

Then, brighter even than the sun rising in the sky, a wall of flames leaped ahead of them. Sullen, blood red those were, giving off a black, greasy smoke which was forming a thick fog.

If that was meant to blind them, it had no effect upon the machine in which they sheltered. For that began again its ponderous advance onward, though all Thora could see was fog and raging flame. She expected to feel the heat of that through the shell of these walls, roasting them. For this was not just a barrier of fire, it spread quickly into a pool encompassing them.

But they felt no heat as on they went. Until before them, looming high as they so deliberately approached, was the bulk of the fortress. This was unlike any structure Thora had seen—more as if someone had found a mountain of stone and then set about rendering it into a citadel within walls nature herself had provided. There were slits which might be windows, but those were few, narrow, and placed well above ground level. While there was no sign of any door.

At last the crawler pulled to a halt facing a sullen reach of dark stone. Then into Thora's mind shot a sudden sharp command. She knew that came from Tarkin—even as her hands moved to obey and her voice repeated it aloud as if to better impress it upon her mind:

“Blue—yellow—white!”

Those were among the color pits on the board and she touched each in just that sequence. She saw that Makil was doing the same, trailed by Borkin a breath or so later.

There followed a brilliant lance of light, first rippling blue, then yellow, building to a near blinding white—shooting forth in three parts, to unite before those touched the stone. On the far edge of her screen Thora saw the coming of another such beam and believed that must spring from the second machine.

Now answered a sound, faint, far away. Still it hurt her head, seemed to pull at the muscles of her body as if it would take command of

her, flesh and bones. A drummer? If so the crawler provided part protection against that other kind of attack.

Kort howled, pawing at his ears, his more sensitive hearing suffering the most. But, though human bodies twitched, and within Thora, at least, panic grew, they kept their fingers upon the buttons and the lance of light held true.

Held and ate. Beneath its touch rock crumbled, turning red, and then a sickly yellow— finally white. It fell in chunks and then actually melted into sluggish riverlets. The light opened a door where there had been none before.

So they broke the outer ring wall of the Dark fortress and moved on into an open way they had so uncovered. The lance of light shifted before them.

“Blue!” Again that order. Thora snatched away two fingers. The lance of light thinned to show them a pathway, rather than to destroy a barrier.

They trundled down a hall, between great pillars. Thora recognized this for a part of her vision. The thrumming of the drums became stronger. She must hold fast to the edge of the board with one hand in order to keep her seat, make sure her fingers were firmly in place.

The light fanned ahead, showing only emptiness. Where were the fighters Thora had confidently expected to see? That such had not

shown also fed her growing fear. She could not believe that even these alien machines might so easily break the Dark defenses.

The drums—yes, the drums! Her body shook near beyond her ability to control it. That rhythm was stealing away her thoughts, blanking out her awareness. Could just

sound

defeat them so easily?

On went the crawler, not hurrying, continuing at the same steady speed it had kept on its journey across the land. Now that light lance reached and touched—held steady.