Morgan’s Run (38 page)

“You still have not told us why

this

nobody,” said Ike.

“Sir George Rose suggested him originally because he is both efficient and compassionate. His words. However, Phillip is also a rarity in the Royal Navy—speaks a number of foreign tongues very fluently. As his German father was a language teacher, he probably absorbed foreign tongues together with his mother’s milk. He speaks French, German, Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian.”

“Of what use will they be at Botany Bay, where the Indians will speak none of them?” asked Neddy Perrott.

“Of no use at all, but of great use in getting there,” said Mr. Thistlethwaite, striving manfully to be patient—how did Richard put up with them? “There are to be several ports of call, and none of them are English. Teneriffe—Spanish. Cape Verde—Portuguese. Rio de Janeiro—Portuguese. The Cape of Good Hope—Dutch. It is a very delicate business, Neddy. Imagine it! In sails a fleet of ten armed English ships, unannounced, to anchor in a harbor owned by a country we have warred against, or gone a-poaching in its slaving grounds. Mr. Pitt regards it as imperative that the fleet be able to establish excellent relations with the various governors of these ports of call. English? No one will understand a word of it, not a word.”

“Why not use interpreters?” asked Richard.

“And have the dealings go on through an intermediary of low rank?

With the Portuguese and the Spanish?

The most punctilious, protocolic people in existence? And with the Dutch, who would do Satan down if they thought there was a chance to make a profit? No, Mr. Pitt insists that the governor himself be able to communicate directly with every touchy provincial governor between England and Botany Bay. Captain Arthur Phillip’s was the only name came up.” He rumbled a wicked laugh. “Hurhur-hur! It is upon such trivialities, Richard, that events turn. For they are

not

trivialities. Yet who thinks of them when the reckoning is totted up? We envision the likes of Sir Walter Raleigh—ruffler, freebooter, intimate of Good Queen Bess. A flourish of lace handkerchief, a sniff at his pomander, and all fall at his feet, overcome. But quite honestly we do not live in those times. Our modern world is very different, and who knows? Perhaps this nobody, Captain Arthur Phillip, has exactly the qualities this particular task demands. Sir George Rose seems to believe so. And Mr. Pitt and Lord Sydney agree with him. That Admiral Lord Howe does not is immaterial. He may be First Lord of the Admiralty, but the Royal Navy does not rule England yet.”

The rumors

flew as the days drew in again and the intervals between Mr. Zachariah Partridge’s £5 bonuses stretched out, not helped by two weeks of solid rain at the end of November which saw the convicts completely confined to the orlop. Tempers shortened, and those who had come to some sort of arrangement with their shore supervisors or dredgemen whereby they ate extra food on the job found it very hard to go back to Ceres rations, which had not improved in quality or quantity. Mr. Sykes trebled his escort when obliged to be in the same area as a large group of convicts, and the racket upstairs on the Londoners’ deck was audible on the orlop.

They had ways of passing the time; in the absence of gin and rum, chiefly by gambling. Each group owned at least one deck of playing cards and a pair of dice, but not everyone who lost (the stakes varied from food to chores) was gallant about it. Those who could read formed a substratum; perhaps ten per cent of the total number of men exchanged books if they had them or begged books if they did not, though ownership was jealously guarded. And perhaps twenty per cent washed their linen handouts from Mr. Duncan Campbell, stringing them on lines which crisscrossed the beams and made walking for exercise even harder. Though the orlop was not overcrowded, the available space for walking limited the shuffling, head-bowing parade to about fifty men at any one time. The rest had either to sit on the benches or lie on the platforms. In the six months between July and the end of December, Ceres lost 80 men of disease—over a quarter of the entire convict complement, and evenly distributed between the two decks.

Late in December Mr. Thistlethwaite was able to tell them more. By now his audience had greatly enlarged and consisted of all who could understand him—and that number had grown too, thanks to propinquity. Only the slowest rustics among the orlop inmates by now could not follow the speech of those who spoke an English somewhat akin to that written in books, as well as grasp a great deal of flash lingo provided the users of it spoke slowly enough.

“The tenders have been let,” he announced to his listeners, “and some tears have been shed. Mr. Duncan Campbell decided that he had sufficient on his plate with his academies, so ended in not tendering at all. The cheapest tender, from Messrs. Turnbull Macaulay and T. Gregory—seven-and-a-third pence per day per man or woman—did not succeed. Nor did that of the slavers, Messrs. Camden, Calvert & King—Lord Sydney did not think it wise to use a slaving firm for this first expedition, though again the price was cheap. The successful tender is a friend of Campbell’s named William Richards Junior. He describes himself as a ship’s broker, but his interests go well beyond that. He has partners, naturally. And I take it that he is cooperating closely with Campbell. I should tell ye that the lot of the marines to go with ye is not enviable, for they are included in the tender price on much the same rations save that they get rum and flour daily.”

“How many of us are to go?” asked a Lancastrian.

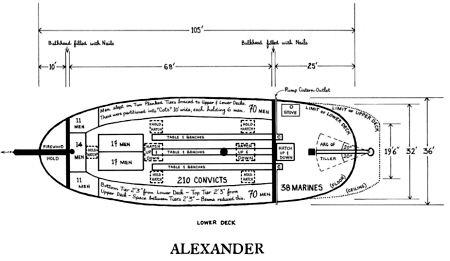

“There are to be five transports to carry about five hundred and eighty male convicts and almost two hundred female, as well as about two hundred marines plus forty wives and assorted children. Three storeships have been commissioned, and the Royal Navy is represented by a tender and an armed vessel which will function as the fleet’s flagship.”

“What are they calling ‘transports’?” asked a Yorkshireman named William Dring. “I am a seaman from Hull, yet it is a sort of ship I do not know.”

“Transports convey men,” said Richard levelly, meeting Dring’s eyes. “In the main, troops to an overseas destination. I believe there are some such, though they would be old by now—the ones used to send troops to the American War had already been used during the Seven Years’ War. And there are coastal transports for ferrying marines and soldiers around England, Scotland and Ireland. They would be far too small. Jem, were there any specifications in the tender for transports?”

“Only that they be shipshape and capable of a long voyage through uncharted seas. They have, I understand, been inspected by the Navy, but how thoroughly I could not say.” Mr. Thistlethwaite drew a breath and decided to be honest. What was the point in giving these poor wretches false hopes? “The truth, of course, is that there was not a rush to offer vessels. What Lord Sydney had counted on, it seems, was an offer from the East India Company, whose ships are the best. He even dangled the bait of the ships’ proceeding directly from Botany Bay to Wampoa in Cathay to pick up cargoes of tea, but the East India Company was not interested. It prefers that its ships call in to Bengal before proceeding to Wampoa, why I do not know. Therefore no source of vessels proven sound for long voyages was at Lord Sydney’s disposal. It may well be that naval inspection consisted in culling the best out of a poor lot.” He looked around at the dismayed faces and regretted his candor. “Do not think, my friends, that ye’ll be embarked upon tubs likely to sink. No ship’s owner can afford to risk his property unduly, even if his underwriters allowed him the opportunity. No, that is not what I am trying to tell ye.”

Richard spoke. “I know what ye’re trying to say, Jem. That our transports are slavers. Why should they not be? Slaving has fallen off since we have been denied access to Georgia and Carolina, not to mention Virginia. There must be any amount of slavers looking for work. And they are already constructed to carry men. Bristol and Liverpool have them tied up along their docks by the score, and some of them are big enough to hold several hundred slaves.”

“Aye, that is it,” sighed Mr. Thistlethwaite. “You are to go in slavers, those of you who will be picked to go.”

“Is there any word of when?” asked Joe Robinson from Hull.

“None.” Mr. Thistlethwaite looked around the circle of faces and grinned. “Still, ’tis Christmastide, and I have arranged for the Ceres orlop to be issued with a half-pint of rum for all hands. Ye will not have the chance for any on the voyage, so do not guzzle it, let it sit a while on your tongues.”

He drew Richard to one side. “I have brought ye another lot of dripstones from Cousin James-the-druggist—Sykes will hand them over, have no fear.” He threw his arms about Richard and hugged him so tightly that none saw the bag of guineas slip from his coat pocket into Richard’s jacket pocket. “ ’Tis all I can do for ye, friend of my heart. Write, I beg, whenever that may be.”

“My thumbs

are pricking,” said Joey Long over supper on the 5th of January, 1787, and shivered.

The others turned to look at him seriously; this simple soul sometimes had premonitions, and they were never wrong.

“Any idea why, Joey?” asked Ike Rogers.

Joey shook his head. “No. They are just pricking.”

But Richard knew. Tomorrow was the 6th, and on each 6th of January for the past two years he had begun the move to a new place of pain. “Joey feels a change coming,” he said. “Tonight we get our things together. We wash, we cut our hair back to the scalp, we comb each other for lice, we make sure no item of clothing or sack or bag or box is unmarked. In the morning they will move us.”

Job Hollister’s lip quivered. “We might not be chosen.”

“We might not. But I think Joey’s thumbs say we will.”

And thank you, Jem Thistlethwaite, for that half-pint of rum. While the Ceres orlop snored, I was able to secret your guineas in our boxes, though no one knows save me.

From

January of 1787

until

January of 1788

A

t dawn the tranfportees were culled, a total of 60 men in

their habitual groups of six, leaving another 73 convicts looking vastly relieved at being passed over. Who, how or why the ten groups chosen to go from the Ceres orlop had been selected no one knew, save that Mr. Hanks and Mr. Sykes had a list and worked from it. The ages of those going varied from fifteen to sixty; most of them (as all the old hands knew) were unskilled, and some of them were sick. Mr. Hanks and Mr. Sykes ignored such considerations; they had their list and that, it seemed, was that.

William Stanley from Seend and the epileptic Mikey Dennison were hopping from foot to foot in glee because they were not on the list. Life on the Ceres orlop was comfortable, there would soon be fresh fleeces.

“Bastards!” Bill Whiting hissed. “Look at them gloat!”

The door opened; four new convicts were thrust inside. Will Connelly and Neddy Perrott squawked simultaneously.

“Crowder, Davis, Martin and Morris from Bristol,” explained Connelly. “They must have been sent from Bristol just for this.”

Bill Whiting gave Richard a broad wink. “Mr. Hanks! Oh, Mr. Hanks!” he called.

“What?” asked Mr. Herbert Hanks, who had been liberally greased in the palm by Mr. James Thistlethwaite and had promised to do his utmost to favor Richard’s and Ike’s groups if they were among those to go. That he was inclined to honor his promise lay in the fact that Mr. Thistlethwaite had whispered of additional largesse after they had gone if his spies informed him that what could be done had indeed been done. “Speak up, cully!”

“Sir, those four men are from Bristol. Are they going?”

“They are,” said Mr. Hanks warily.

The old, merry Whiting looked sideways at Richard, then the round face assumed an expression of diffident humility for Mr. Hanks. “Sir, they are but four. The thing is, we do so hate being parted from Stanley and Dennison, Mr. Hanks, sir. I wondered. . . ?”

Mr. Hanks consulted his list. “I see that the two who were to go with them died yesterday. They is four too many or two too few, whichever way youse looks at it. Stanley and Dennison will round it off real nice.”

“Got you!” said Whiting beneath his breath.

“Thankee, you bugger!” said Ike through his teeth. “I was looking forward to life without that pair.”

Neddy Perrott giggled. “Believe me, Ike, two craftier shits than Crowder and Davis do not exist. William Stanley from Seend will meet his match and more.”

“Besides, Ike,” said Whiting, smiling angelically, “we will need a couple of workers to mop the deck and do the washing.”

The convicts to go were fitted with locked waist bands and locked manacles, but no extensions to their ankles; instead, a long chain was passed from one waist to the next and fused each six men together. Weeping and wailing because they had not sufficient time to gather all the things they needed, Stanley and Dennison were hitched to the four newcomers from Bristol.

“That makes sixty-six of us in eleven groups,” said Richard.

Ike grimaced. “And at least that many from London.”

But that, as they found out later, was not the case. Only six groups of six were chosen from upstairs, and by no means confined to the true flash coves of an Old Bailey conviction and the London Newgate; most were from around London and many of those from Kent of the Thames, particularly Deptford. Why, no one knew, even Mr. Hanks, who simply followed his list. The whole expedition was a mystery to all who had dealings with it, whether a part of it or whether remaining behind.

His box and two canvas sacks by his side, Richard told the orlop transportees off: one gang from Yorkshire and Durham, one from Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, one from Hampshire, three from Berkshire, Wiltshire, Sussex and Oxfordshire, and three from the West Country. With an occasional oddment. But Richard’s puzzle-loving mind had long ago made certain deductions: some parts of England produced convicts galore, while others like Cumberland and a large tract of counties around Leicestershire produced none at all. Why was that? Too bucolic? Too sparsely populated? No, Richard did not think so. It depended upon the judges.

* * *

Two big

lighters lay alongside. The three West Country groups and the two groups from around Yorkshire were loaded into the first—a tight fit—and the six remaining groups were squeezed perilously into the second boat. At about ten o’clock on that fine, cold morning the oarsmen stroked off downriver toward the great bend in the half-mile-wide Thames just to the east of Woolwich. Traffic was light, but the news had gotten around; the denizens of bum boats, dredges and other small craft waved, whistled shrilly and cheered, while the men on the dangerously overloaded second boat prayed no one sailed past close enough to create a wake ripple.

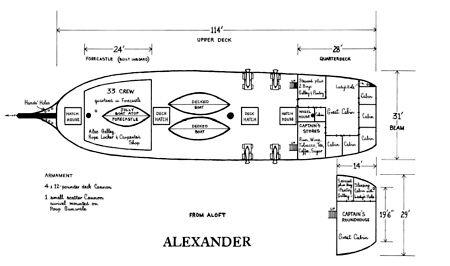

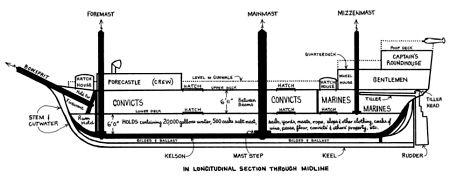

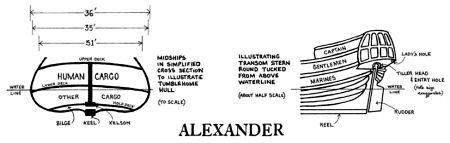

Around the curve lay Gallion’s Reach, an anchorage for big ships occupied on that day by two vessels only, one about two-thirds the size of the other. Richard’s heart sank. The larger vessel had not changed a scrap—a ship-rigged barque standing about fourteen feet from gunwales to water, which meant she had no cargo aboard—no poop and no forecastle, just a quarterdeck and a galley aft of the foremast. Stripped for speed and action.

His eyes met those belonging to Connelly and Perrott.

“Alexander,” said Neddy Perrott hollowly.

Richard’s mouth was a thin line. “Aye, that’s her.”

“Ye know her?” asked Ike.

“That we do,” said Connelly grimly. “A slaver out of Bristol, late a privateer. Famous for dying crews and dying cargoes.”

Ike swallowed. “And the other?”

“I do not know her, so she ain’t from Bristol,” said Richard. “She will have a bronze plate screwed to her hull at the stern, so we ought to be able to see it. We are going to Alexander.”

The nameplate said she was Lady Penrhyn.

“Out of Liverpool and built special for slaving,” said Aaron Davis, one of the newcomers from Bristol. “Brand new, by the look of her. What a maiden voyage! Lord Penrhyn must be desperate.”

“No sign of anyone going aboard her,” said Bill Whiting.

“She will fill up, never fear,” said Richard.

They had

to get themselves and their gear up a rope ladder to an opening in the gunwale amidships, a twelve-foot climb. Those ahead of his group were not encumbered by boxes, but even when their chains became entangled in the rungs and supports no one appeared in the gap above to help.

Luckily the chain connecting them ran free and distance between each of them could be expanded or contracted. “Bunch up and give me all the chain,” said Richard when their turn came. He tossed both his sacks up, used his manacles to cradle his box, and scaled those few feet in a hurry to make sure no one already up had the presence of mind to pinch one of his sacks. Once aboard, he gathered in his stuff and took the boxes his fellows handed up to him.

Alexander’s two longboats and her jollyboat had been taken off the deck and put in the water, so there was room for Richard to move his three West Country groups out of the way. Confusion was his initial impression; knots of scarlet-coated marines stood about looking like thunder, two sashed marine officers and two corporals manned a small scatter cannon swiveled on the quarterdeck rail, and a motley collection of sailors hung from the shrouds or perched on various kennels like spectators at a boxing match in a meadow.

What happens now? As there was no one to ask, he watched the confusion grow ever worse. Long before all eleven lots of convicts were on the deck the place resembled a menagerie—an impression added to by dozens of goats, sheep, pigs, geese and ducks running all over the place pursued by a dozen excited dogs. Feeling someone watching him fixedly from above, he lifted his head to see a large marmalade cat balanced comfortably on a low spar surveying the chaos with an expression of bored cynicism. Of gaolers there were none; they had stayed behind on Ceres, responsibility for the transportees ended.

“Soldiers,” whispered Billy Earl from rural Wiltshire.

“Marines,” corrected Neddy Perrott. “White facings on their coats. Soldiers have colored facings.”