Moscow, December 25th, 1991 (29 page)

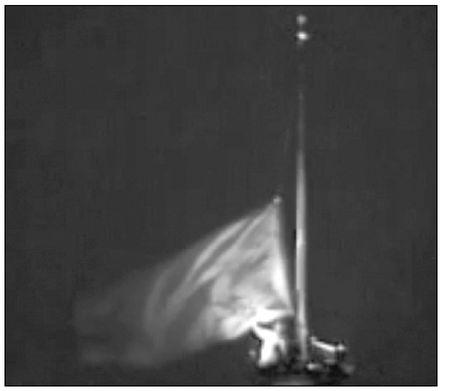

DECEMBER 25, 1991: Kremlin officials lower red flag from Senate Dome for last time. ABC Television

DECEMBER 25, 1991: Kremlin officials gather in red flag.

ABC Television

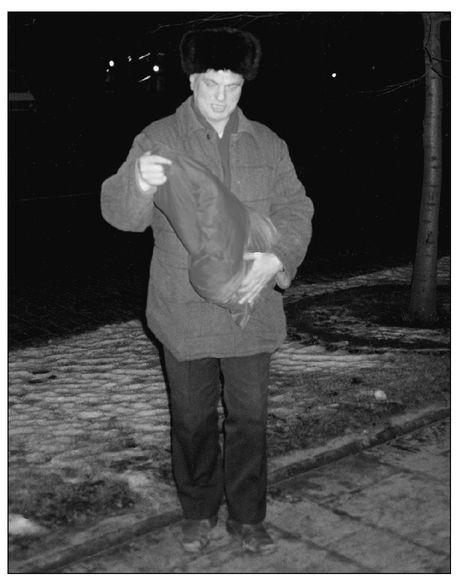

DECEMBER 25, 1991: Kremlin worker takes bundled-up red flag to storage basement.

Courtesy

of Stuart H Loory

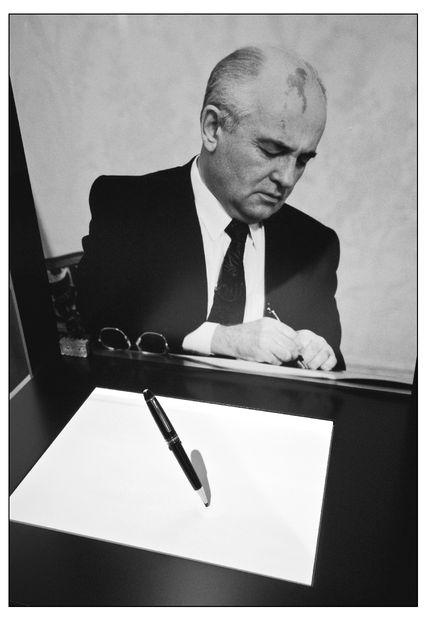

Pen used by Gorbachev to end Soviet Union on display in Newseum in Washington.

Courtesy Tom Johnson

Gorbachev’s apartment building in Lenin Hills from which he was evicted the day he resigned.

Author

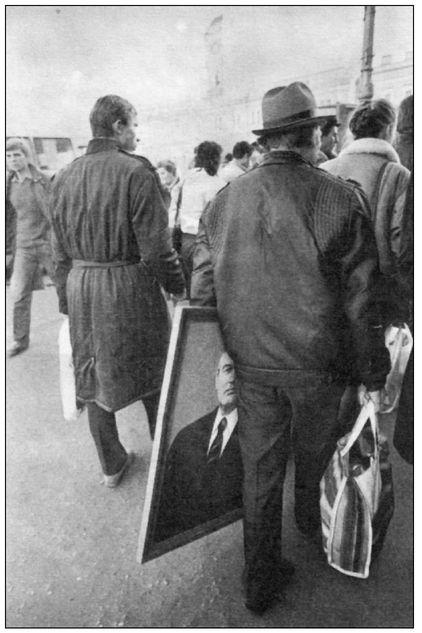

DECEMBER 26, 1991: Gorbachev’s official portrait being disposed of by official in St. Petersburg.

Novosti

Yeltsin meets Bush shortly after his triumph over Gorbachev, and at last becomes a member of the club of world leaders.

Courtesy George Bush Presidential Library and Museum

Senate Building today with new Russian flag flying above Gorbachev’s former Kremlin office, now ceremonial residence of President Medvedev.

Author

CHAPTER 18

DECEMBER 25: DUSK

With less than sixty minutes left before his resignation address, Mikhail Gorbachev is at last mentally and physically ready. His speech has been printed out for him in large letters to read on air. He is satisfied that he has found the right tone to express his disappointment and feelings of betrayal by Yeltsin in a dignified manner.

While waiting, he gives Ted Koppel the benefit of a few more of his thoughts. Then as the ABC team goes out into the Kremlin corridor, he signals to Yegor Yakovlev and Andrey Grachev to stay. “Let’s have coffee,” he says.

The three sit at the oval table where Gorbachev likes to chat with visitors. Zhenya, the waiter, brings in a tray with coffee, pastries, and small open sandwiches.

Grachev senses that Gorbachev does not want to be left alone “with his thoughts, his undelivered speech and the nuclear suitcase which he would soon have to give up.”

1

They discuss whether Gorbachev should sign his decree resigning the presidency of the Soviet Union before giving his televised address, or vice versa. Yakovlev advises him to do it after. He thinks it better that everyone watching television sees him doing it. It would add a moment of drama and finality. The more formalism there is to the event, the more it will be seen as a dignified exit.

They are all rather disheartened by the fact that no ceremony has been arranged by the incoming authorities for the first peaceful transition of power in Russian history.

As they sip their coffee, the conversation of the three men spontaneously turns to their apprehensions about what might happen to them in the future.

The fate of Nicolae Ceauşescu is not far from their minds. Two years ago—to the day—the Romanian communist leader and his wife, Elena, were executed by firing squad after an uprising against his totalitarian rule. Gorbachev regarded Ceauşescu with contempt as the “Romanian führer,” but they had maintained a high-profile relationship. Twenty days before the execution, Gorbachev had told Ceauşescu, who was visiting Moscow, that he had no reason to fear the collapse or the end of socialism, and they had agreed on a meeting of prime ministers on January 9. Gorbachev made a strange remark to the departing Ceauşescu. “You shall be alive on the ninth of January,” he said.

2

By that date Ceauşescu was dead.

Grachev voices a more realistic fear that the Yeltsin people will start a process to make Gorbachev the fall guy for the past, as the Germans have done to Erich Honecker. This is something that has been exercising the mind of Anatoly Chernyaev all week. Perhaps nothing will happen, he had written in his diary as the end neared. They are Russians, not Germans, after all, and already people are feeling sorry for Gorbachev. But this is not France either. Unlike de Gaulle, Gorbachev will never be allowed to return. So far everything has been done by civilized standards, but they have no guarantee that sometime in the future Yeltsin might not try to discredit them all to justify his destruction of the Union. Grachev asks Gorbachev whether he is concerned that somebody would try to get revenge on him by ferreting around in his past.

“I’m not worried,” replies Gorbachev, though he is aware that there have been attempts before to pin something on him for his lifestyle as first party secretary in Stavropol from 1970 to 1978. Eduard Shevardnadze told him once that in 1984, in the jostling for power in the Politburo before Chernenko died, officials at the interior ministry were instructed by a rival of Gorbachev to dig up compromising material on his Stavropol days.

3

Gorbachev himself received a jolt two years ago when Andrey Sakharov took him aside to warn him of a plot to besmirch his name. Huddled together on chairs in a corner of the dimly lit stage in the Kremlin Palace of Congresses following a session of the Congress of People’s Deputies, the former dissident confided to Gorbachev that he had evidence the

nomenklatura,

the Soviet Union’s high-ranking officials, were out to get him. The Nobel Prize—winning physicist was quite specific. “You are vulnerable to pressure, to blackmail, by people who control the channels of information. They threaten to publish certain information unless you do as they wish.... Even now they are saying you took bribes in Stavropol; 160,000 rubles has been mentioned.”

4

Gorbachev suspected that Yeltsin was behind the rumors, but Sakharov may have been referring to hardliners plotting to discredit the president and seize power.

Now that the issue has been raised again by Grachev, Gorbachev insists there is nothing for him to worry about. “My conscience is clear. Do you really think there could have been any very extraordinary privileges available in Stavropol? There were no special apartments, not even a special store. We bought our food at the canteen of the district party committee. Until recently Raisa Maximovna was keeping all our receipts.”

“And what about Krasnodar?” asks Grachev. “Krasnodar is right next door to you, and some incredible things went on there at Medunov’s.” There had been a notorious case of corruption in the Krasnodar region next to Stavropol involving the first secretary, Sergey Medunov, a favorite of Brezhnev’s. “Medunov, he’s something else again,” exclaims Gorbachev. “I read complaints against him myself, especially from the local Jewish population, bribes, extortion, and what orgies in the official dachas! He wasn’t afraid of anything. And for good reason. He had direct access to Brezhnev.”