Moses and Akhenaten (2 page)

Read Moses and Akhenaten Online

Authors: Ahmed Osman

By the early years of this century, when the city of Amarna had been excavated and more was known about Akhenaten and his family, he became a focus of interest for Egyptologists of the period, who saw him as a visionary humanitarian as well as the first monotheist. Akhenaten was revealed as a revolutionary king, who abolished the Ancient Egyptian religious system, with its many deities represented by fetish or animal shapes. He replaced the old gods with a sole God, the Aten, who had no image or form, a universal God not just for Egypt, but also for Kush (Nubia) in the south and Syria in the north, a God for the whole world.

He was a poet who wrote the hymn to Aten that has a striking resemblance to Psalm 104 of the Bible. He instructed his artists to express freely what they felt and saw, resulting in a new and simple realistic art that was different in many respects from the traditional form of Egyptian artistic expression. We were allowed to see the king as a human being with his wife and daughters, eating, drinking and making offerings to the Aten. Nor was he like the military prototype of Pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Although the kings and princes of Western Asia tried hard to involve him in recurrent wars, he refused to become a party to their disputes. It is no wonder that the early Egyptologists of this century saw in him an expression of their own modern ideas.

âThe most remarkable of all the Pharaohs and the first individual in human history' are the words that James Henry Breasted, the American scholar, chose to describe him.

1

It is a theme he returned to and developed in a later book: âIt is important to notice ⦠that Akhenaten was a prophet ⦠Like Jesus, who, on the one hand drew his lessons from the lilies of the field, the fowls of the air or the clouds of the sky, and, on the other hand, from the human society about him in stories like the Prodigal Son, the Good Samaritan or the woman who lost her piece of money, so this revolutionary Egyptian prophet drew his teachings from a contemplation both of nature and of human life â¦'

2

The same theme finds an echo in the work of Arthur Weigall, the British Egyptologist: â⦠at the name of Akhenaten there emerges from the darkness a figure more clear than that of any other Pharaoh, and with it there comes the singing of the birds, the voices of the children and the scent of many flowers. For once we may look right into the mind of a King of Egypt and may see something of its workings, and all that is there observed is worthy of admiration. Akhenaten has been called “the first individual in human history”; but if he is thus the first historical figure whose personality is known to us, he is also the first of all human founders of religious doctrines. Akhenaten may be ranked in degree of time, and, in view of the new ground broken by him, perhaps in degree of genius, as the world's first idealist.'

3

For the Reverend James Baikie, another British Egyptologist, he was â⦠an idealist dreamer, who actually believed that men were meant to live in truth and speak the truth.'

4

Not all scholars, however, took such an enthusiastic and flattering view of the first of the Amarna kings. Some, like the British philologist Alan H. Gardiner, wrote of him that âthe standing colossi from his peristyle court at Karnak have a look of fanatical determination, such as his subsequent history confirmed only too fatally':

5

John Pendlebury, who was involved in much of the early exploration at Amarna, came to the conclusion: âHis [Akhenaten's] main preoccupation was with religion. He and [Queen] Nefertiti became devotees of the Aten. Today we should call them religious maniacs.'

6

The controversial nature of Akhenaten's character and teachings eventually engaged the interest of Sigmund Freud, the Jewish father of psychoanalysis, who introduced a new element into the debate as Europe began its lurch towards war in the middle of the 1930s. In July 1934 Freud wrote the draft of what would later become the first part of his book

Moses and Monotheism.

This introductory section was published initially in the German magazine

Imago

in 1937 under the headline âMoses an Egyptian'.

Freud demonstrated in this article that the name of the Jewish leader was not derived from Hebrew, as had been thought up to that time, but had as its source an Egyptian word,

mos,

meaning a child. He showed also that the story of the birth of Moses is a replica of other ancient myths about the birth of some of the great heroes of history. Freud pointed out, however, that the myth of Moses' birth and exposure stands apart from those of other heroes and varies from them on one essential point. In order to hide the fact that Moses was Egyptian, the myth of his birth has been reversed to make him born to humble parents and succoured by the high-status family: âIt is very different in the case of Moses. Here the first family â usually so distinguished â is modest enough. He is a child of Jewish Levites. But the second family â the humble one in which as a rule heroes are brought up â is replaced by the royal house of Egypt. This divergence from the usual type has struck many research workers as strange.'

Later in 1937

Imago

published a further article by Freud under the title âIf Moses was an Egyptian'. This dealt with the question of why the Jewish law-giver, if actually Egyptian, should have passed on to his followers a monotheistic belief rather than the classical Ancient Egyptian plethora of gods and images. At the same time, Freud found great similarity between the new religion that Akhenaten had tried to impose on his country and the religious teaching attributed to Moses. For example, he wrote: âThe Jewish creed says:

“Schema Yisrael Adonai Elohenu Adonai Echod”.'

(âHear, O Israel, the Lord thy God is one God'.) As the Hebrew letter

d

is a transliteration of the Egyptian letter

t

and

e

becomes

o

, he went on to explain that this sentence from the Jewish creed could be translated: âHear, O Israel, our God Aten is the only God.'

A short time after publication of these two articles, Freud was reported to be suffering from cancer. Three months after the Germans invaded Austria, in June 1938, he left Vienna and sought refuge in London where, feeling his end approaching, he decided that he wished to see the two articles, plus a third section, written in Vienna but hitherto unpublished, make their appearance in the form of a book in English. This, he felt, would provide a fitting climax to his distinguished life. His intentions did not meet with the approval of a number of Jewish scholars, however: they felt that some of his views, and, in particular, his claim in the unpublished third section that Moses had been murdered by his own followers in protest against the harshness of his monotheistic beliefs, could only add to the problems of the Jews, already facing a new and harsh Oppression by the Nazis. Professor Abraham S. Yahuda, the American Jewish theologian and philologist, visited Freud at his new home in Hampstead, London, and begged him not to publish his book, but Freud refused to be deterred and

Moses and Monotheism

made its first appearance in March 1939. In his book Freud suggested that one of Akhenaten's high officials, probably called Tuthmose, was an adherent of the Aten religion. After the death of the king, Tuthmose selected the Hebrew tribe, already living at Goshen in the Eastern Delta, to be his chosen people, took them out of Egypt at the time of the Exodus and passed on to them the tenets of Akhenaten's religion.

Freud died at the age of 83, six months after his book was published. The outbreak of the Second World War not only brought all excavations in Egypt to an end, but delayed response to the bombshell that Freud had left behind. This was not too long in being remedied once the world returned to peace. The new contestant to enter the lists was another Jewish psychoanalyst, Immanuel Velikovsky, who had been born and educated in Russia in the early years of this century and had then emigrated to Palestine before settling in the United States. In 1952 he published the first part of his book

Ages in Chaos,

in which he tried to use some evidence of volcanic eruptions in Sinai to date the Jewish Exodus from Egypt at the start of the Eighteenth Dynasty, two centuries before the reign of Akhenaten, in order to place Moses at a distant point in history that

preceded

the Egyptian king. Not only that. In a separate work,

Oedipus and Akhenaten,

he set out to show that Oedipus of this classic Greek myth had an Egyptian historical origin and that Akhenaten was the Oedipus king who married his own mother, Queen Tiye.

The work of Velikovsky may be said to have set the tone in the post-war years for assessments of Akhenaten. Scholars have been on the whole at pains to destroy his flattering early image and to sever any connection between him and the monotheism of Moses. One of the earliest to embark on this crusade was Cyril Aldred, the Scottish Egyptologist. In his book about the first of the Amarna kings, published in 1968, he tried to explain the absence of genitalia in a nude colossus of the king from Karnak by the fact that Akhenaten must have been the victim of a distressing disease:

All the indications are that such peculiar physical characteristics were the result of a complaint known to physicians and pathologists as Fröhlich's Syndrome. Male patients with this disorder frequently exhibit a corpulence similar to Akhenaten's. The genitalia remain infantile and may be so embedded in fat as not to be visible. Adiposity may vary in degree, but there is a typical feminine distribution of fat in the region of the breasts, abdomen, pubis, thighs and buttocks. The lower limbs, however, are slender and the legs, for instance, resemble plus-fours ⦠There is warrant for thinking that he suffered from Fröhlich's Syndrome and wished to have himself represented with all those deformities that distinguished his appearance from the rest of humanity.

7

However, we do have conclusive evidence that Akhenaten had at least six daughters by Queen Nefertiti. Aldred put forward an ingenious explanation for this apparent contradiction: âUntil recently it was possible to speculate that, though the daughters of Nefertiti are described as begotten of a king, it is by no means certain that such a king was Akhenaten, particularly if Amenhotep III was still alive two years after the youngest had been born. Though it may seem preposterous that Amenhotep III should have undertaken the marital duties of a sterile coregent, in the milieu of divine kingship such an enlargement of his responsibilities is not unthinkable.'

Later in the same book, however, he tells us that Akhenaten was not, after all, impotent. The author contradicts his earlier speculation by suggesting that Akhenaten married his own eldest daughter, Merytaten, and fathered a child by her: âOn the death of Nefertiti, her place was taken by Merytaten ⦠It would appear that she was the mother of a Princess Merytaten-the-less, from a recently published inscription from Hermopolis [The city across the river from Amarna where Ramses II had used Amarna stones for his building], but it is impossible to say who the father was, though the inference seems to be that it was Akhenaten.'

The author then goes on even to suggest that the king had a homosexual relationship with his brother/coregent/son-in-law, Semenkhkare. Aldred's attempt to destroy the earlier flattering image of Akhenaten took him down a path that a number of other scholars proved only too happy to follow. The most recent was Professor Donald Redford of Toronto University, an eminent scholar of both Old Testament studies and Egyptology, who wrote in his book

Akhenaten, the Heretic King,

published in 1984:

The historical Akhenaten is markedly different from the figure popularists have created for us. Humanist he was not, and certainly no humanitarian romantic. To make of him a tragic âChrist-like' figure is a sheer falsehood. Nor is he the mentor of Moses: a vast gulf is fixed between the rigid, coercive, rarified monotheism of the Pharaoh and Hebrew henotheism [belief in one God without asserting that he is the only God] which in any case we see through the distorted prism of texts written seven hundred years after Akhenaten's death.

Redford summarizes his distaste for the king in the following words: âA man deemed ugly by the accepted standards of the day, secluded in the palace in his minority, certainly close to his mother, possibly ignored by his father, outshone by his brother and sisters, unsure of himself, Akhenaten suffered the singular misfortune of acceding to the throne of Egypt and its empire.' And then: âIf the king and his circle inspire me somewhat with contempt, it is apprehension I feel when I contemplate his “religion”.'

8

The post-war attempt to crucify Akhenaten and discredit his religion has been unanimous in the sense that any scholars who may hold less hostile views have maintained a suspicious silence. At the root of the campaign of vilification lies a desire to enhance Moses and his monotheism by discrediting Akhenaten, the Egyptian intruder, and the beliefs he attempted to introduce into his country. Ironically, those scholars who have led this ruthless campaign chose the wrong target. In attacking Akhenaten, they were, in fact, attacking their own hero â for, as Freud came so close to demonstrating, Akhenaten and Moses were one and the same person.

Some of the arguments in support of this statement are of necessity long and complicated, and the ordinary reader may find them difficult to follow and somewhat wearing. Where it seemed appropriate I have therefore tried to summarize such arguments briefly, plus the conclusions to be drawn from them, and, for those who wish more detail, given a fuller account in a series of appendices.

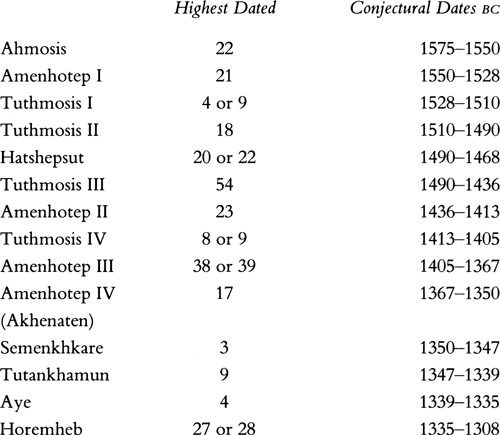

CHRONOLOGY OF THE EIGHTEENTH DYNASTY