Mother Nature: The Journals of Eleanor O'Kell

Read Mother Nature: The Journals of Eleanor O'Kell Online

Authors: Michael Conniff

Tags: #Science Fiction

BOOK OF O’KELLS:

MOTHER NATURE

By Michael Conniff

BOOK OF O’KELLS: MOTHER NATURE

Copyright © 2014 by Michael Conniff

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof

may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever

without the express written permission of the publisher

except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Printed in the United States of America

First Printing, 2014

Murray Lane Press

37 Sagewood Court

Basalt, CO 81621

For Janice, who makes everything possible.

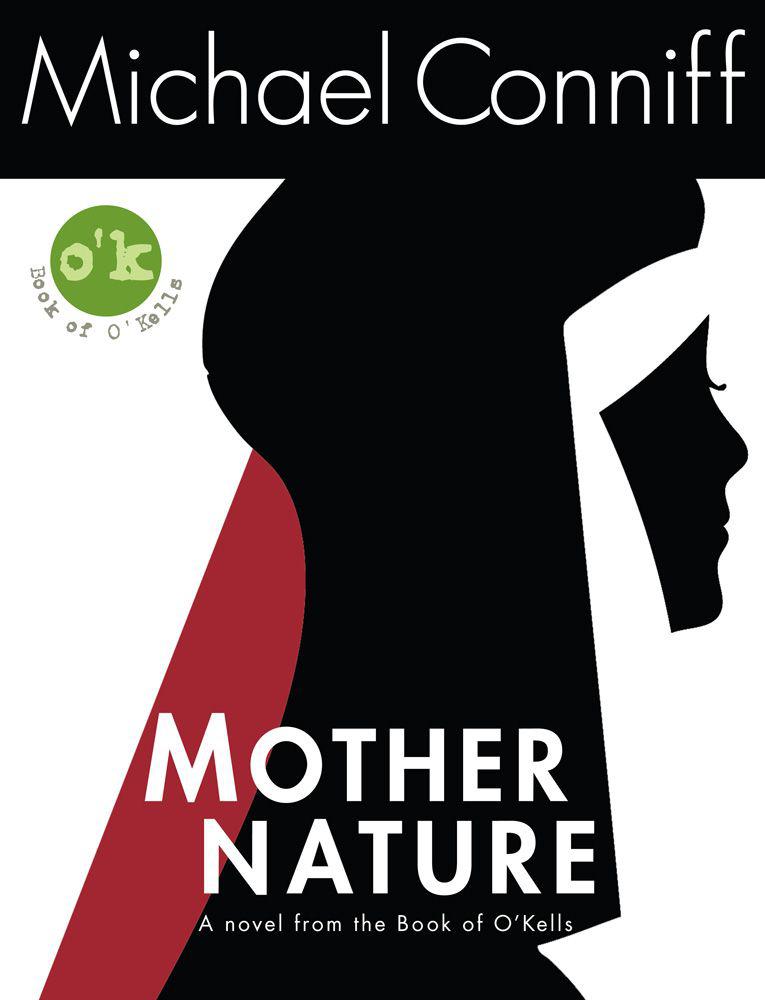

Michael Conniff is a co-founder of The Isaacson School for New Media at Colorado Mountain College and head of the Digital Story Lab at the school; in 2013 he was selected Faculty of the Year by students at CMC Aspen for his Isaacson School workshops. He is also CEO of Post Time Media, a social media and multimedia branding and storytelling company based in Aspen. His novel, MOTHER NATURE, is part of his multimedia, multi-platform BOOK OF O’KELLS, including novels, the first Facebook novel, a novella, mysteries, a play, a screenplay, a documentary, and the graphic novel ATOMIC TOM. A graduate of Harvard with honors in history, he has published a dozen short stories and was selected as a Scholar at the Breadloaf Writers Conference.

Michael Conniff’s Story on Facebook

TABLE OF CONTENTS

About The Author

The Forties

The Fifties

The Sixties

The Seventies

The Eighties

The Nineties

Oral History: Eleanor O’Kell

Afterword

BOOK OF O’KELLS:

SINS OF THE FLESH (Excerpt)

MOTHER NATURE

The Journals Of Eleanor O’Kell

August 15, 1948

Bucky Harwell? Could it be that I was

really

going to marry

him

? Oh, I know what I was thinking—that Bucky had money and that I could get away from my half-brother, my family, my life. But there is a better way, Your Way, Dear Lord. Thank you for sending me Bucky to see that. It wasn’t Bucky’s money—O’Kells have money, I won’t ever need money—and Bucky wasn’t so bad. He always looked like he had been hosed down when he came to The Big House, his hair all slicked all the way back, his teeth still wet from brushing, the line of his nose sharp enough to cut the wind. Bucky gave me beautiful things when he came, big bouquets or a broach, and then a ring when he broached

the

question. I said yes because I liked Bucky. I liked touching his old body, imagining what a rich man who did not look half-bad might have touched before. From then on, wearing his ring, I allowed Bucky his liberties and confessed to every one of them every week, until Father Loughlin told me he thought I had either a calling or a husband, that he could hear them both in my voice. Forgive me, Father, but I still think of Bucky with his tennis shorts down around his ankles, the soft roll of his belly salty from our game, set, match. Forgive me if that’s the Bucky I knew and the Bucky I

know

. I still think of him sometimes when I’m not thinking of You, Lord. I see now how You were tempting me with all the joys of a life not worth living. I thank you for that, Lord. I will always thank You for letting me see and feel and even touch it.

We are still not allowed to talk here—I don’t even know if I’m allowed to write this to You. But I have to. I miss everyone and everything—I miss my freedom, Lord, my old wonderfully shallow life. I even miss Bucky Harwell…not Bucky really, but the life he lived, that

we

lived, the life where nothing mattered at all. That’s what I gave up for You, a life where nothing mattered. Saying it that way doesn’t make it seem so bad, does it? Tennis never mattered. Cocktails at The Big House never mattered. The parties in Southampton never

ever

mattered. Still I miss it, Lord. I admit it. I admit to being shallow and callow and callous before my calling. You were the one who came calling Lord. It was You whom I loved all the while. I’m sure of it. I’m sure of it now.

It’s so beautiful here on the ocean with winter coming on. I watch the seagulls flap harder for every scrap and know how lucky I am to walk with You. I need no miracles, Lord, nothing but the prayer that brings me so close to life everlasting. Was I crazy to give up all the riches of the world? Maybe. But to hold on to those riches and thus never to know this love for You… how could

that

have been a life worth living? Now I can see your love in every living thing, in the birds that fly by overhead, in every life that I touch, in the way the wind keeps whispering in my ear. Your scraps are my feast.

Nightmares. Can’t sleep, Lord. Can’t think. Don’t know why. What’s wrong with me? What’s wrong?

Thanksgiving here by the sea with You and Your Sisters of Mercy. Everything to give thanks for here. My freedom from family, from want. My love of You, the love I feel for my Sisters. We are a gaggle of girls at dinner, gabbing away about our new lives and our old, odd loves. I even tell everyone about Bucky, though no one can believe how rich I really was. They are all impressed by my devotion to the Sisters because I had so much to give up, though it never seems that way to me. I go to the chapel afterwards with my new friend Mother St. Joseph, to thank you Lord, and to think again of what I was so glad to give up for You. Here I have a room, good food, the love of good friends, and the love of God. What have I given up that was worth the keeping?

More nightmares. Shapes. I wake up trying to remember but nothing comes.

I fall to my knees and pray to You for help to remember, for help to forget.

Lord, I know all things, good and bad, happen for a reason, and that I have to always trust in you. But I can’t eat, Lord, I can’t sleep. Why do You make me suffer like this? Is it because of all the damned O’Kell money? I would renounce it all if the Sisters would let me, but I can’t touch it now that it’s in the blind trust. Is it because of my wicked thoughts about Bucky? I’m sorry, Lord. I’ve prayed for forgiveness for what I have done with him, for even thinking about doing it ever again. I’m sorry, Lord. God I’m sorry. I would give anything if You would m

ake the shapes go away at night, if I could only sleep with You.

We Sisters are all chittering away like birds because the Order is ready to send us on our way, on

Your

Way. It is a wonderful thing, though we will miss the Convent and each other terribly. What friends I’ve made here, especially Mother St. Joseph! She and I pray we won’t ever be too far apart. But the wonderful thing about the Order is that we are

never

apart forever, we are

always

close to You and to each other. And we know we will see each other again, we will always have these friends in the next city or the next town or the next country. We have so much to give to Your people, Lord. We Sisters can’t wait to start giving. Send me where You will!

My heart is broken because the Sisters ask me to stay

here

to help with the accounting, though just for a little while. They seem to think I have a way with numbers, because of the O’Kell in me. Mother St. Joseph has been sent clear across the country. My heart is broken and then broken again.

August 29, 1949

Mother St. Joseph and I kiss and hug. I whisper goodbye to all of my Sisters, all of us crying all the while. They are all scattering like seeds all over the country. Everyone except for me. I will be left in this empty nest. Why, Lord? Why

me

?

September 4, 1949

Whenever I look at the numbers my head drops and I fall asleep until the shapes come back. The Sisters don’t mind if I fall asleep at my desk because I work so far into the night.

My brother Will writes me to say he is so glad that I am not going anywhere. I wish I could see it as a blessing, as Your Way, but so far I can’t. Please help me, Lord.

December 8, 1949

Maybe it does help to be an O’Kell, even in a Convent. In my case, You have blessed me with the gifts of a businessman. You have brought me here to praise You, and the best way to praise You is to take our Order from the Dark Ages and out into the light. All of our hospitals and old folks homes and missions are run as if they have nothing to do with each other. A bar of soap is a bar of soap, I say, and if the Order can order all the soap together then there is real money to be saved on every bar. That’s just part of what I see, Lord. Our Order has so much valuable real estate in so many places if we only had eyes to see. We need to build up what we have so we can give so much more to Your lambs, to those most in need. Without profitability there can be no charity.

I am so tired, Lord. The shapes keep me from sleeping, so now I stay up all night to work or to pray in Your Name. Sometimes the prayer carries right over into sleep, so that I sleep with You, for hours at a time if my heart and soul are pure. If I can’t sleep with You, I pray all night You will make the awful shapes go away. It’s getting worse, Lord, not better. I can hear it, smell it, sometimes the shapes makes me taste it. It is so awful, Lord. I beg You for Your help—or Your forgiveness. Please grant me rest.

Can a nun be in a wedding party? All those beautiful gowns, and then this

thing

in black and white with a crucifix around her neck? I tell Becca that she would be far better off marrying Joe Gemma without her sister the Sister on the altar. I suggest that I read a Psalm from the pulpit instead, and she accepts. I don’t know anything about Joe, and I haven’t even met him. Becca says he writes television shows. I’ve never met anyone who writes television shows before.

Mother St. Agnes has taken me under her wing. She does all the books for the Order, but she is too old to keep going for much longer. She asks me if I have any ideas about how we might do things better. I prayed on it—Lord knows I have my ideas—there are some things we can do right away. With all of our schools and hospitals and missions, we’re more like a business than an Order, but we run the business of our Order like a corner store. I pray to God to guide my hand.

I am so tired, Lord. Please let me sleep with You.

Rebecca wants to be married in Southampton, in

The Big House, with all of us there, with all of Southampton

and

New York there, and Father had to use all of his influence to make it so. So far as anybody knows there has

never

been a marriage with Mass in a private home anywhere in the country before. But Father built a private chapel on our property big enough to hold 500, then he told the Cardinal this is where he would be marrying his daughter. The Cardinal petitioned the Pope, who gave his blessing (after Father made his contribution, of course). The Sacrament will be present on our property. It never hurts to have money. It never hurts to be an O’Kell.

Becca gets me alone on the beach because she has to tell me something. I now what’s coming—that she’s

married. You’re what? I say. “I’m married, Eleanor. Joe and I went to City Hall months ago.” Oh my God, I say. “You won’t tell anyone, will you?” Not a soul, I say. “Is it a sin?” Becca wonders, and I don’t know what to say.

Lord, I was jumping around the dance floor like a sailor on leave

—me with my habit flying like a sail. I was a debutante, again, if you can tell from all the times I was asked to dance by all the young men. Even a Sister has the right to be a girl at her sister’s wedding! I was somber enough at the ceremony, reading my Psalm, with Becca glowing behind her veil, and Joe Gemma blinking his eyes like he just couldn’t believe what he was marrying into when he took the ring from Will. Father’s chapel behind The Big House was buffed and beautiful, and the sun was high enough outside to make the stained glass dance a jig. The Bishop sang High Mass in Latin with enough priests for a whole parish on the altar. Becca was giggling all the way through, that’s how happy she was, and Diana, the maiden of honor, looked serious enough to be the one getting married. Half of Southampton was at the reception and

all

of New York. There were whole roasts cut thin as paper, and roasted garlic potatoes that started to melt the moment they met your mouth, and beautiful yellow squash cut into tiny strips, and huge strawberries and champagne and so many other things. Joe brought his friends from New York, a bunch of funny Jewish men on television that I had never heard of, Sid and Carl and a women they called Imagine Cocoa. What a funny name, like a drink! By the end of the night they were all drinking out in the kitchen. I know they’ve never seen anything like an O’Kell wedding before. I’m not quite sure what Becca sees in Joe. He’s older, for one thing, and Becca tells me he believes in things about the country, without saying exactly what. Everyone was talking about who would have the next wedding, as if we didn’t already know. Diana and Henry Ford II were coo-cooing the whole day. We all stood still for all kinds of pictures—I’m half-afraid my black habit ruined every one, but beautiful Becca was laughing and carrying on so much in her white gown there was no way to worry about anything. I’ve never seen her so happy, so much in love, so ready to live. Even my brother (

half

-brother) Tom smiled once. At least I thought it was a smile.

Haven’t been able to sleep more than an hour or two since the wedding. I’m praying more and sleeping less. The shapes are worse than ever, bigger and

darker. In my dream I start screaming as loud as I can until the shapes choke me and I can’t breathe. There’s a rolling in my dreams now, like I’m on a boat, and the windows are round like a ship’s, but it’s always so dark I don’t know where I am.

Becca came to visit and she is

so

upset. It’s not the marriage. She loves Joe dearly, and she loves him more and more now that he’s on the blacklist. Becca is scared because Joe has been ordered to Washington to testify with a bunch of other writers from his television show. Becca said Joe went to a Communist meeting once. She says he never even joined the Party, but you don’t have to be a member to be in trouble. Becca says Joe was young when he did it, that he really didn’t know what he was doing. She cried and cried. So did I. Our sins

always

come back to haunt us.

What a blessing! Wall Street

loves

our hospital bonds! And why shouldn’t they? It’s not like the Sisters of Mercy are going to run out on their obligations. (That would be a sin!) They know bonds from the Sisters will always be good, or that we’ll make good on them. I am beginning to like the business of God.

My sister

Diana came to see me. Like Becca, she cried non-stop for an hour. I had seen the newspapers. Henry Ford is going to marry Charlotte McDonnell, if you can believe that. Diana couldn’t. She said Henry had just told her how much he loved her, how he had to be near her, that he was a Ford, she was an O’Kell, and they could live wherever Diana wanted, forever, together. She’s blaming it on Tom for some reason, saying Tom is behind everything, that it was Tom who connected Joe Gemma to Oppenheimer, that a Ford can’t marry a woman who has a Communist for a brother-in-law. “That’s just the way Tom works,” Diana said. “If you weren’t in the Convent you would know it.” I find that hard to believe and I tell her so.

The rolling again, all night, like my room is pitching back and forth in a storm. Then a bang through the round window big enough to take off my head. The shapes in my dreams are now one shape

—a man with his hand over my mouth so tight that I am choking. I try to bite him and to kick him but he’s too big, too strong. He has the smell of a man, too, and his beard is like a scrub brush scrubbing my cheek. I scream but no one can hear me in my dream because the bang is so big outside.

We are just back from Wall Street after selling off more of our bonds. Mother St. Agnes

loves

the idea of being a financier, but she has not been well, and only our trips to the city make her whole. She says “a young girl and an old lady” make a good team, but the people on Wall Street still don’t know what to make of us.

Joe was fired from his job at NBC and Becca says no one will touch him, they won’t even take his calls any more. Not that money is a problem, it never is for us, but Joe won’t even get out of bed in the morning. He sits in his study with the shades down and the lights off, like his life is over. Becca tells him to keep writing, that writers can

always

write as long as they have a pencil and a piece of paper, that things will change. But Joe won’t buy it. Becca says he’s acting like he’s already dead.

Thinking about Rebecca and Diana and me as young girls at the breakfast table. Why do we look so ashamed?

Father has not been well since Becca’s wedding. He caught cold that night and he’s still coughing. It’s not like Father to be sick, not compared to Mother, who is

always

sick, but she is worried about him, and none of the remedies have worked. Mother’s afraid that it might be walking pneumonia. Thank goodness Tom knows enough about the business to take over.

I always hope

this

night will be the night I sleep. But I never do.

Father is finally taking a turn for the better, thank God. The pneumonia is gone and he’s back on his feet. Becca says he scratches away on his copper plates, the raw ideas of his inventions, until they pile up like dishes.

Terrible nightmares

again

. I can see the shape is a man. I smell his smell and I hear his breathing above the bomb exploding outside. There is no way to stop him or to say no. I see a cloud of smoke like a mushroom through the little round window high behind me and I scream.

Please forgive me, Lord!

Mother St. Agnes died last night in her sleep. I cried and cried all day—I’m still crying. She was so good to me, so kind, a saint always by my side. She wore her habit lightly, like a smock you put on when it’s time to play with clay. At her funeral, I said she was the older sister I never had, and that I hoped she would hold a place for me in heaven by her side. I miss her so much already.

Mother Superior ordered me to see a doctor to get sleeping pills. That’s how bad I must look since Mother St. Agnes died, like the walking dead. The pills work too well and now I make it through my day feeling sluggish, drugged. All the Sisters here at the Convent tell me I look so much better, but I don’t feel it. It’s almost like I miss my exhaustion, my explosions, the living hell of my dreams.

So quiet here, with the numbers, without Mother St. Agnes. I have to take over all the accounting for the Order. It’s so different being in charge. I don’t know quite what to do, where to begin. I will never have her shoulder to cry upon again, though some nights I can hear her talking to me all the way from Heaven. She says it’s so beautiful in ways she never could have imagined.

Diana came to see me again with that ridiculous tennis player Luigi Campobello. Oh, Luigi

is

beautiful, black curly hair above pink cheeks, a body so hard you could bounce a ball on it. But he is so egotistical! Maybe it’s the way all men in Italy are. I don’t know. But I do know that every conversation, every sentence has to be about Luigi. Luigi

this

, Diana says, and then Luigi

that

. She’s so upset about Henry Ford that she’s going to marry his worst nightmare—and ours.

I can’t take the pills any more. I don’t want to feel

that

way all the time, like my brain is under water. Before I was exhausted, but at least I was myself. (A very tired version of myself.) With the pills, my body and my mind are starting to feel more and more like mush, like I have no mind of my own.

Father is dead. Becca and Diana came to tell me and we cried and cried. He was so smart, he had to start with nothing, and all you have to do is to turn on a light switch to see what he meant to everyone. But I wish I could feel more for him. I wish I could have known him better. I would have asked him what he found so fascinating about those copper plates where he scratched out his inventions. I’ll never forget the one time he was scratching something on one of those plates and I tried to climb up on his lap and he brushed me aside like I was a fly. I never tried to climb up again.

Father’s funeral was hell. He left instructions that we were to have it in the chapel he built for Rebecca’s wedding at The Big House, but his funeral could have filled St. Patrick’s Cathedral, where Mother wanted to do it. There were limousines backed up all the way to Gin Lane trying to get in. The Mayor of New York was there, and the Governor, and the Cardinal, everyone there to pay their respects. There must have been a thousand people outside, listening to the public address system Mother had put up next to the entrance. High Mass dragged on and on, and a cold wind came off the water and froze everyone stiff. Tom gave the eulogy, the list of all the things that Father had done and all of his good deeds. Then I had to read another Psalm, crying the whole time. We buried Father on the bluff looking out over the sea, in the Sacred Ground of our family plot. Will could not stop shivering. It was so cold up there once the sun stopped shining.