Mother of Purl (11 page)

Authors: Edith Eig,Caroline Greeven

Backstitch

.

Backstitching is similar to the stitch made by a sewing machine and is very firm because you work over the seam twice. If you’ve ever hand–sewn a seam, you will be familiar with this technique. Backstitching is the simple motion of stitching forward one stitch, then bringing your needle back to reenter the fabric halfway down that stitch. So basically for every stitch worked, you are only moving forward half a stitch.

- Put the two pieces you will be sewing on top of each other, with the right sides facing inward (as if the finished sweater has been turned inside out and is lying flat). Take a few moments to make sure the edges of the sweater where you will be seaming are fully aligned. Using straight pins, pin the edges together as close to the edge as possible.

- Thread embroidery floss or yarn through a darning needle that is similar in color to your knitting yarn, and insert the needle through both layers of knitting at the bottom of the sweater. Backstitch several times to secure your thread. Now work up the sides, always backstitching as you go.

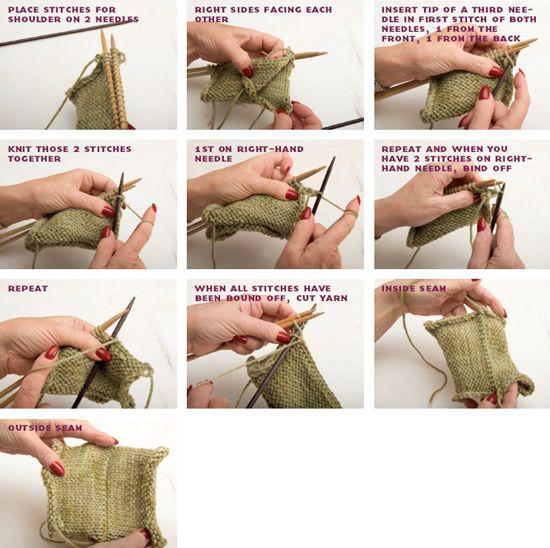

Although most patterns suggest binding off the shoulders and then sewing them together, I prefer the three–needle bind–off method because it results in a smooth, clean, and invisible shoulder seam. It’s also much easier to do. There is nothing more unsightly than a bulky shoulder seam. Remember to take into account that you must knit the stitches for the shoulder that would have otherwise been cast off.

When you’ve finished the back and front of your sweater, don’t bind off the shoulders. Instead, place those stitches on a stitch holder, leaving a long tail of yarn about four times the length of your shoulder to knit the shoulders together, then cut the yarn. With the right sides of the sweater facing each other, replace the stitch holders with your knitting needles,

taking care to make sure the two points of the needle are facing the same direction. Take a third needle to join the shoulders together. Insert the third needle into the first stitch of the other two needles and knit them together. Next, knit the second two stitches together. When you have two stitches on your right–hand needle, bind them off. Repeat across the row, binding off as you go. Note that the needles replacing the stitch holders function as holders themselves, so you can use a different size needle as long as your third needle is the same size you used to knit your sweater.

Ah, success! You’ve successfully completed your very first sweater. Congratulations. Everyone’s quite impressed with your work. Only you seem to notice that it needs some minor adjustments: it could have been a bit roomier in the body, or perhaps you want the seams pressed. There is a simple solution. It’s called blocking.

[

EDITH KNIT TIPS

]Stitch Holders

When using stitch holders, it’s a good idea to turn them upside down on your work so that should it open up accidentally, your stitches won’t fall off.

Blocking is the process by which you dampen your finished garment with cold water and, pinning it onto a towel, gently stretch it until it dries in the shape that the pattern called for.

Find a large flat area to lay out your towel and garment where it can remain undisturbed for at least a day. If it’s exposed to sunshine, so much the better—it will help to dry your sweater even faster—but avoid direct light as it might fade the color. Special blocking boards are also available for purchase, but this is not essential. What is essential is stainless steel T–shaped blocking pins. These are heavier than ordinary straight pins you might use in sewing, and they won’t rust.

Here are few tips to help you learn to block:

- I recommend you use the schematic from your pattern as a guide. Or, if you prefer, you can take one of your favorite sweaters that is similar in shape as a guide to block your garment.

Lay the damp sweater on the towel and pin out the shoulders, starting from the center. Make sure your pins don’t push through the actual material, but rather just through the yarn loops at the edge of the sweater, and take care to use enough pins to ensure that your yarn won’t stretch unevenly. - If you want to make your sweater a little wider or longer, gently pull the sweater either outward or downward as you pin along the top, sides, and bottom. While you are pulling it into shape, remember to

ease

the sweater, rather than tugging on it roughly. Refer back to your schematic or guide sweater as you go.

Once you’ve finished blocking your garment, check to ensure that the edges of your sweater have smooth lines. Now leave it to dry.

Another technique for shaping a finished garment is steaming, an even easier process than blocking. Start by laying a dry towel on an ironing board or a flat surface, then place your garment on the towel. Next, take a very wet (but not dripping) towel and lay it on your knitting. Using a warm setting on your iron, lightly steam over the towel, quickly and gently touching it. Leave the wet towel in place on the garment overnight. The weight of the towel will be enough to block your garment. In the morning, remove the towel and let it air–dry.

[

EDITH KNIT TIPS

]Remember Where You Put It …

When you are seaming your sweater, you need to bury the loose end of your seaming thread. However, keep in mind there may be a time when you might need to undo the seaming, so you’ll want to make sure you leave a bit of the tail visible.

Fill up a plastic tub with cold water and add a capful of Eucalan—an Australian product made from the eucalyptus plant, which I happen to find to be one of the most effective, safest, and most gentle cleansers. I only recommend this, as some popular wool wash detergents will discolor your yarn. The choice of washing agent is more important than you may realize. Washing dyed natural yarns may fade the color, and washing garments made of animal fibers, such as wool or cashmere, causes them to lose their lanolin—the natural oil in animal fiber that keeps the garment soft and protects the individual fibers from breakage. Once you have washed a sweater several times, you have effectively stripped it of its lanolin, and your sweater will lose its elasticity and softness. Eucalan and other similar washing agents on the market restore the vibrancy and life of the fabric. Trust me, you’ll be amazed.

At some point, every knitter is bound to make a mistake—sometimes it’s small and other times it’s colossal. Perhaps there’s a purl when you should have knitted, or your cable twisted in the wrong direction. The result is devastating and you see it as a glaring mistake. These are heartwrenching moments. For some mysterious reason, such mistakes tend to be in the most obvious place. What to do? Well, the first thing to do is put the piece down and walk away, thus avoiding your first impulse to rip it out or toss it. After you’ve had a chance to compose yourself, you can begin to think about how to fix it.

There are several ways to fix a mistake or remedy a problem, other than ripping out your entire work. One of the first thing you can do is put away the pattern and look at your creation objectively. So your sweater looks a bit different than the original design. Let’s make the best of the worst. I’ve had women come in with sweaters that had been ruined by bleach spots—we embroidered over them or added a decorative item. Sweaters that were too small—we added a side panel to both sides to increase the circumference. Be brave and make a design feature out of your mistake. The key is to not be afraid to take risks in repairing your work.

Remember that your knitting is a flexible, forgiving medium. If you can approach your problem creatively, you can probably figure out a way to work with it. Here are some knitting mistakes we’ve encountered at the store and the solutions we found to fix them.

[

EDITH KNIT TIPS

]Washing Wisely

To avoid the risk of felting your garment, only use cold water and let it soak for the recommend time noted on the label. When using Eucalan or like products, do not rinse; just gently squeeze (and don’t ring it) out the excess water. Preferably, place the garment in the spin cycle of your washing machine to remove the excess water. Lay it on a flat surface to dry.

TO ERR IS HUMAN

Take a look at a sweater you purchased from a department store. No matter what the style, you know the tension will be perfect, the stitch work flawless. Machines don’t make mistakes. If you find a flaw in your hand–knit sweater, don’t be disheartened by it. That flaw means you’re human, and it reflects the uniqueness of your work, proof that, unlike mass–produced sweaters, yours is one of a kind. For example, did you know that when you tour the United Nations, the guide will point out the flaws in the most amazing handmade wall hangings, explaining, “If it was perfect, it would have been made by the hands of God.” In fact, I have a client who purposely leaves one wrong stitch in her work. This stems from the time she accidentally made a slight mistake and refused to rip it out. This has become her trademark.

- One of my clients, Jodi, is very creative and passionate about her knitting. She only makes a few pieces a year and strives to make them perfect and beautiful. Unfortunately, they don’t always end up as perfect as they could, since she doesn’t always heed my advice. This January her big project was a pretty, hot pink cardigan, knitted in a bulky wool, with a long fringe trim around the edges. The sweater turned out lopsided, with one side of the front hanging lower than the other. Disaster. Jodi was distraught. I looked at it for a minute and realized that all we had to do was a little nip ‘n’ tuck. Instead of ripping out the front, I threaded a piece of yarn up the sagging

side, hiding the thread between the heavy fringe and the front band. As the other women in the knitting circle looked on, I pulled gently at the yarn until the fronts were even and then anchored the yarn at the neckline, making sure the stitches were evenly spaced along the band. This isn’t always the solution for sagging sweaters, especially if they sag more than one inch, but it worked with her design. - Eliza is a sporadic knitter. I may see her every day for a month, then not see her for a year. Because she doesn’t knit consistently, her work often has flaws. Recently she came in with a poncho she had just completed. The neck was far too wide and slid annoyingly down her shoulders. I knew that if Eliza couldn’t save this project, she’d probably give up knitting for good, so I devised a way to fix it. I suggested she crochet a band around the neck, working with a contrasting yarn so it looked like a design feature. However, instead of picking up every stitch, I had her pick up three stitches for every four, ending up with forty–five stitches instead of the sixty she started with. This narrowed the neckline enough so that the poncho now sat comfortably on her shoulders. Eliza was happy with the result, and she even comes to the knitting circle a little more frequently than she did before.

- Felting is a one–way process; it can’t be undone—most of the time. A newcomer to the shop’s knitting circle had spent many months finishing a mohair sweater—only to find that her very efficient housekeeper had ruined it in the washer and dryer. I didn’t want her to become discouraged and throw in the knitting towel. I wasn’t sure whether I could fix this felting problem, but I intended to try a process that had worked for me in the past. I took her sweater home and immersed it in cold water in my washing machine, using a highly sudsy shampoo, like Prell. I let it soak overnight, then ran the spin

cycle

without rinsing it,

and stretched it into shape and let it dry. The delicate mohair blossomed again, and the sweater was almost as good as new. When I gave it to her, I suggested she “not wear this one in the rain.” - Rather than toss that oversized sweater from the ‘80s, you might consider cutting it down to size. You’ll want to find a tailor who has a serger machine to prevent the stitches from running as the sweater is cut and sewn back together.

- One of my clients ran out of wool for her scarf and I didn’t have any more, so I divided a ball of novelty yarn, and we knitted at either end of the scarf so that the different yarn was a design feature rather than a fix.