Mr. Bones (46 page)

Authors: Paul Theroux

“What did the man say to that?”

“He couldn't speak. He looked like he'd been slapped in the face. He was disarmed. There was nothing he could do. Because forgiveness is final.”

“That's beautiful,” Mother said, and took my hand. “I'll cherish that lovely thought. You could write about that.”

I looked away. I said, “And I keep meeting old friends here. Some of them are having health problems. I feel as if I can be useful.”

“You've always been kind that way, Jay.”

I returned to the hospice the following day. Murray Cutler looked at me with dread when he saw me enter the room, but he was too inarticulate to object, and, bedridden, unable to do anything but watch me seat myself and stare, he was the helpless one now.

“I knew a couple, very creative woman, very entrepreneurial man, partners in the trucking business”âjust the sound of my voice made Murray Cutler hug himself in fear. “They split up. She said to me, âYou have no idea. He was always hearing voices. His mother visited him in his office. The voices said, “Stab her in the eye! Stab her in the eye!”' He explained this in detail to his wife. âYou need to know.' His father had died in a plane crash. He refused ever to get on a plane, but that was all rightâhis whole business plan concerned freight in long-haul trucks. His other quirk was that he had to take thirty steps whenever he entered a room, so if a room only used up twenty steps he marched in place for ten more, but very subtly. I asked her, âWhat was the attraction?' She loved him, and she told me, âHe had the charm that all psychopaths have.'”

In the time it took me to tell this story, the tension left Murray Cutler's body, and when I finished he said in his usual mutter, with a half-smile, “What's the point?”

“No one knew that he was crazy.” I shifted to be closer to him. I said in a harsh whisper, “Only she suffered, and when she told her story no one believed her. But I believed her. And as for the man, his punishmentâhe still heard the voices.”

The door opened, one of the nurses pushing a trolley with food trays on it. I was near enough to Murray Cutler to whisper to him without being overheard, “I'll be back.”

The day of my father's funeral was so scripted, and adhered so closely to the script, it seemed that his death was the fulfillment of a long-range plan, that this was the last act in the ritual. I was grateful for that, for the sequence of events that numbed me by their routine, following a set of cues: our designated seats, the vases of flowers, the chanting priest, the candle flames, the kind words, nothing jarring; and then the casket on wheels, the silent hearse sliding importantly to the cemetery, where the grave had been thoughtfully dug and the muddy hole disguised with a rectangle of purple satin fringed with gold ribbon; more prayers, more flowers, and then another procession, the withdrawal, all of it expected. We were sad, but no one cried. The nature and purpose of a ritual is to meet expectations; it is the unexpected that is upsetting.

Murray Cutler cringed when I appeared the following afternoon, later than I usually visited. He must have thought with relief that I was not coming, but then to see me at the end of the day, when he was tired and having to face another story, was demoralizing to him.

He tried to cover his face as I pulled the chair close to his bed and began speaking.

“I knew a woman who visited Greece on vacation,” I said. “A man stopped her on a back street in Athens, where she'd been buying souvenirs. He said, âI had a dream last night of Jesus Christ. Jesus said to me, “You must go to this particular street. There you will meet a beautiful woman.” And here you are.' When she turned to get away, a man in a doorway said, âCome here. I will help you,' and the woman fled into his house. The man locked the door and raped her. And when he was done, the other man was waiting to do the same.”

Murray Cutler, seeming to undergo a seizure, raised his arms as though to defend himself, and he cowered behind a tangle of plastic tubes.

“Raped her,” I said, leaning over and showing him my teeth.

Sitting beside my grieving mother, helping her answer the condolence notes, took almost a week. My father had many elderly friends, and none of them used a computer. Rather than send a printed card as thanks for these spidery scrawls, my mother feltâand I agreedâthat it was best to write each person a reply that reflected their degree of intimacy toward my father. It was a sensitive business, but it brought my mother and me closer. When she grew weary she put her hand on mine as I was writing, improving her responses to these people, and said, “Everything's going to be all right.”

Murray Cutler was much worse the next time I saw him, a few days later. I locked the door to the room, and he groaned when I sat down and started to speak.

“There was a man who, when he lusted after someone and didn't want to be caught, pawed his prey in public placesâin the bleachers at baseball games, in the back rows at concerts, in popular campgrounds. He possessed them by pawing them openly, looking like a dear friend and benefactor, and that was the paradox, because the victim was too fearful to make a scene. And when the victim went home he couldn't report what had happened. He had to think of a story, but in his story he was not a victim. He was triumphant. He invented dramas and dialogue. He became such an expert at evasion that the oblique habit of storytelling became his profession.”

Murray Cutler faced me and never looked more like meat, and he tried to turn away, but he was too weak. “Yet one story always stood for another. He invented the truth,” I said. “Now you tell me a story.”

I sat watching him, and it was as if a succession of episodes might be running through his mind, all their cruel details twitching on his face.

I returned to my own empty room in my mother's house. I relived all the hopes and fantasies one feels in a childhood bedroom. I suffered the overfamiliar ceiling, the walls, the window: like a cell I'd served a sentence in, that I was confined to again. I hardly stirred from the house until a month later, to accompany Mother to the gravesite. “I want to visit Dad,” she had said at breakfast that day, cutting a sausage, then putting down her knife.

We were standing at the grave when Mother said, “Your teacher Murray Cutler died. It was in the paper.”

I couldn't speak.

“Dad respected him so much. He was a Harvard graduate, you know. Dad was so proud that he took you under his wing. What's wrong?”

I had begun to cry, sniffling, then sobbing with an odd hopeless honk of despair.

“He thought the world of you,” she said. “Dad knew that. He used to talk about it to me.” And then she was comforting me. “Go on, let it out, Jay, I know how much he meant to you.”

Â

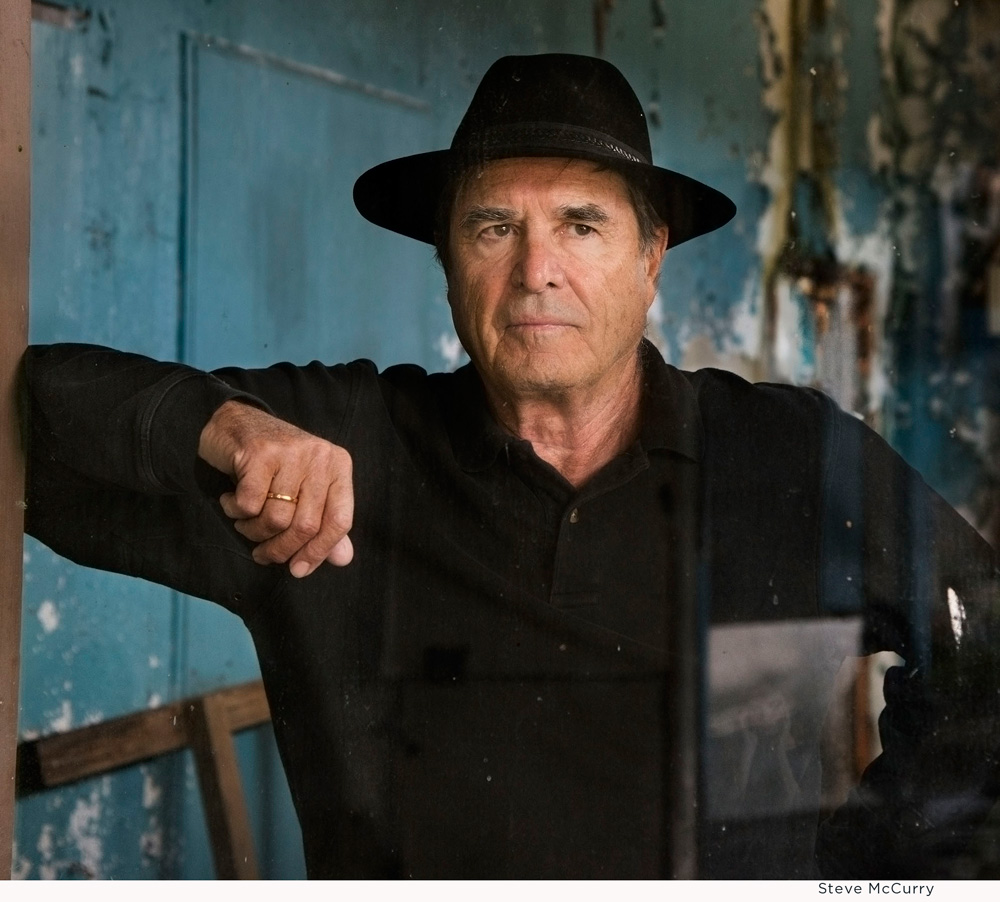

P

AUL

T

HEROUX

is the author of many highly acclaimed books. His novels include

The Lower River

and

The Mosquito Coast,

and his renowned travel books include

Ghost Train to the Eastern Star

and

Dark Star Safari.

He lives in Hawaii and on Cape Cod.