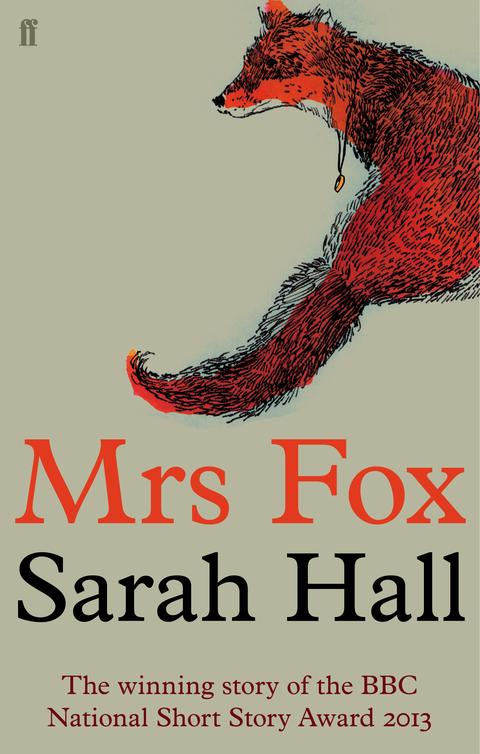

Mrs Fox

Authors: Sarah Hall

Sarah Hall

For Lucy and Tom

THAT HE LOVES HIS WIFE

is unquestionable. All day at work he looks forward to seeing her. On the train home, he reads, glancing up at the stations of commuter towns, land-steal under construction, slabs of mineral-looking earth, and pluming clouds. He imagines her robe falling as she steps across the bedroom. Usually he arrives first, while she drives back from her office. He pours a drink and reclines on the sofa. When the front door opens he rouses. He tries to wait, for her to come and find him, and tell him about her day, but he hasn’t the patience. She is in the kitchen, taking her coat off, unfastening her shoes. Her form, her essence, a scent of corrupted rose.

–Hello, darling, she says.

The shape of her eyes, almost Persian, though she is English. Her waist and hips in the blue skirt; he watches her move – to the sink, to the table, to the chair where she sits, slowly, with a woman’s grace. Under the hollow of her throat, below the collar of her blouse, is a dribble of fine gold, a chain, on which hangs her wedding ring.

–Hello, you.

He bends to kiss her, his hands in his pockets. Such simple pleasure; she is his to kiss.

He, or she, cooks; this is the modern world, both of them are capable, both busy. They eat dinner, sometimes they drink wine. They talk or listen to music; nothing in particular. There are no children yet.

Later, they move upstairs and prepare for bed. He washes his face, urinates. He likes to leave the day on his body. He wears nothing to sleep in; neither does his wife, but she has showered, her hair is damp, darkened to wheat. Her skin is incredibly soft; there is no corrugation on her rump. Her pubic hair is harsh when it dries; it crackles against his palm, contrasts strangely with what’s inside. A mystery he wants to solve every night. There are positions they favour, that feel and make them appear unusual to each other. The trick is to remain slightly detached. The trick is to be able to bite, to speak in a voice not your own. Afterwards, she goes to the bathroom, attends to herself, and comes back to bed. His sleep is blissful, dreamless.

Of course, this is not the truth. No man is entirely contented. He has stray erotic thoughts, and irritations. She is slow to pay bills. She is messy in the bathroom; he picks up bundles of wet towels every day. Occasionally, he uses pornography, if he is away for work. He fantasizes about other women, some of whom look like old girlfriends, some like his wife. If a woman at work or on the train arouses him, he wonders about the alternative, a replacement. But in the wake of these moments, he suffers vertiginous fear, imagines losing her, and he understands what she means. It is its absence which defines the importance of a thing.

And what of this wife? She is in part unknowable, as all clever women are. The marrow is adaptable, which is not to say she is guileful, just that she will survive. Only once has she been unfaithful. She is desirable, but to elicit adoration there must be more than sexual qualities. Something in her childhood has made her withheld. She makes no romantic claims, does not require reassurance, and he adores her because of the lack. The one who loves less is always loved more. After she has cleaned herself and joined him in bed, she dreams subterranean dreams, of forests, dark corridors and burrows, roots and earth. In her purse, alongside the makeup and money, is a small purple ball. A useless item, but she keeps it – who can say why? She is called Sophia.

Their house is modern, in a town in the corona of the city. Its colours are arable: brassica, taupe, flax. True angles, long surfaces, invisible, soft-closing drawers. The mortgage is large. They have invested in bricks, in the concept of home. A cleaner comes on Thursdays. There are similar houses nearby, newly built along the edgelands, in the lesser countryside – what was once heath.

*

One morning he wakes to find his wife vomiting into the toilet. She is kneeling, retching, but nothing is coming up. She is holding the bowl. As she leans forward the notches in her spine rise against the flesh of her back. Her protruding bones, the wide-open mouth, a clicking sound in her gullet: the scene is disconcerting, his wife is almost never ill. He touches her shoulder.

–Are you all right? Can I do anything?

She turns. Her eyes are bright, the brightness of fever. There is a coppery gleam under her skin. She shakes her head. Whatever is rising in her has passed. She closes the lid, flushes, and stands. She leans over the sink and drinks from the tap, not sips, but long sucks of water. She dries her mouth on a towel.

–I’m fine.

She lays a hand, briefly, on his chest, then moves past him into the bedroom. She begins to dress, zips up her skirt, fits her heels into the backs of her shoes.

–I won’t have breakfast. I’ll get something later. See you tonight.

She kisses him goodbye. Her breath is slightly sour. He hears the front door slam and the car engine start. His wife has a strong constitution. She does not often take to her bed. In the year they met she had some kind of mass removed, through an opened abdomen; she got up and walked the hospital corridors the same day. He goes into the kitchen and cooks an egg. Then he too leaves for work.

Later, he will wonder, and through the day he worries. But that evening, when they return to the house, will herald only good things. She seems well again, radiant even, having signed a new contract at work for the sale of a block of satellite offices. The greenish hue to her skin is gone. Her hair is undone and all about her shoulders. She pulls him forward by his tie.

–Thank you for being so sweet this morning.

They kiss. He feels relief, but over what he’s not sure. He untucks her blouse, slips his fingers under the waistband of her skirt. She indicates her willingness. They move upstairs and reduce each other to nakedness. He bends before her. A wide badge of hair, undepilated, spreads at the top of her thighs. The taste reminds him of a river. They take longer than usual. He is strung between immense climactic pleasure and delay. She does not come, but she is ardent; finally he cannot hold back.

They eat late – cereal in bed – spilling milk from the edges of the bowls, like children. They laugh at the small domestic adventure; it’s as if they have just met.

Tomorrow is the weekend, when time becomes luxurious. But his wife does not sleep late, as she usually would. When he wakes she is already up, in the bathroom. There is the sound of running water, and under its flow another sound, the low cry of someone expressing injury, a burn, or a cut, a cry like a bird, but wider of throat. Once, twice, he hears it. Is she sick again? He knocks on the door.

–Sophia?

She doesn’t answer. She is a private woman; this is her business. Perhaps she is fighting a flu. He goes to the kitchen to make coffee. Soon she joins him. She has bathed and dressed but does not look well. Her face is pinched, dark around the eye sockets, markedly so, as if an overnight gauntening has taken place.

–Oh, poor you, he says. What would you like to do today? We could stay here and take it easy, if you don’t feel well.

–Walk, she says. I’d like some air.

He makes toast for her but she takes only a bite or two. He notices that the last chewed mouthful has been put back on her plate, a damp little brown pile. She keeps looking towards the window.

–Would you like to go for a walk now? he asks.

She nods and stands. At the back door she pulls on leather boots, a coat, a yellow scarf, and moves restlessly while he finds his jacket. They walk through the cul-de-sac, ringed by calluna houses, past the children’s play area at the end of the road, the concrete pit with conical mounds where children skate. It is still early; no one is around. Intimations of frost under north-facing gables. Behind the morning mist, a faint October sun has begun its industry. They walk through a gateway onto scrubland, then into diminutive trees, young ash, recently planted around the skirt of the older woods. Two miles away, on the other side of the heath, towards the city, bulldozers are levelling the earth, extending the road system.

Sophia walks quickly on the dirt path, perhaps trying to walk away the virus, the malaise, whatever it is that’s upsetting her system. The path rises and falls, chicanes permissively. There are ferns and grasses, twigs angling up, leaf-spoils, the brittle memory of wild garlic and summer flowers. Towards the centre, a few older trees have survived; their branches heavy, their bark flaking, trunks starred with orange lichen. Birds dip and dart between bushes. The light breaks through; a gilded light, terrestrial but somehow holy. She moves ahead. They do not speak, but it is not uncompanionable. He allows himself, for a few moments, to be troubled by irrational thoughts – she has a rapid, senseless cancer and will waste, there will be unconscionable pain, he will hold a fatal vigil beside her bed. Outliving her will be dire. Her memory will be like a wound in him. But, as he watches her stride in front, he can see that she is fit and healthy. Her body swings, full of energy. What is it then? An unhappiness? A confliction? He dares not ask.

The woods begin to thicken: oak and beech. A jay flaps across the thicket, lands on the ground nearby; he admires the primary blue elbow before it flutters off. Sophia turns her head sharply in the direction of its flight. She picks up her pace and begins to walk strangely on the tips of her toes, her knees bent, her heels lifted. Then she leans forward and in a keen, awkward position begins to run. She runs hard. Her feet toss up fragments of turf and flares of leaves. Her hair gleams – the chromic sun renders it livid. She runs, at full tilt, as if pursued.

–Hey, he calls. Hey! Stop! Where are you going?

Fifty yards away, she slows and stops. She crouches on the path as he hurries after her, her body twitching in an effort to remain still. He catches up.

–What was all that about! Darling?

She turns her head and smiles. Something is wrong with her face. The bones have been recarved. Her lips are thin and her nose is a dark blade. Teeth small and yellow. The lashes of her hazel eyes have thickened and her brows are drawn together, an expression he has never seen, a look that is almost craven. A trick of kiltering light on this English autumn morning. The deep cast of shadows from the canopy. He blinks. She turns to face the forest again. She is leaning forward, putting her hands down, lifting her bottom. She has stepped out of her laced boots and is walking away. Now she is running again, on all fours, lower to earth, sleeker, fleeter. She is running and becoming smaller, running and becoming smaller, running in the light of the reddening sun, the red of her hair and her coat falling, the red of her fur and her body loosening. Running. Holding behind her a sudden, brazen object, white-tipped. Her yellow scarf trails in the briar. All vestiges shed. She stops, within calling distance, were he not struck dumb. She looks over her shoulder. Topaz eyes glinting. Scorched face. Vixen.

October light, no less duplicitous than any season’s. Bird calls. Plants shriveling. The moon, palely bent on the horizon, is setting. Everything, swift or slow, continues. He looks at the fox on the path in front of him. Any moment, his wife will walk between the bushes. She will crawl out of the wen of woven ferns. The undergrowth, which must surely have taken her, will yield her.

How amazing,

she’ll whisper, pointing up the track. These are his thoughts, standing in the morning sun, staring, and wrestling belief. Insects pass from stalk to stalk. The breeze through the trees is sibilant.

On the path, looking back at him, is a brilliant creature, which does not move, does not flinch or sidle off. No. She turns fully and hoists the tail around beside her like a flaming sceptre. Slim limbs and slender nose. A badge of white from jaw to breast. Her head thrust low and forward, as if she is looking along the earth into the future. His mind’s a shock of useless thought, denying, hectoring, until one lone voice proceeds through the chaos.

You saw, you saw, you saw.

He says half words, nothing sensible. And now she trots towards him down the path, as a dog would, returning to its master.

Nerve and instinct. Her thousand feral programs. Should she not flee into the borders, kicking away the manmade world? She comes to him, her coy, sporting body held on elegant black-socked legs. A moment ago: Sophia. He stands still. His mind stops exchanging. At his feet, she sits, her tail rearing. Exceptional, winged ears. Eyes like the spectrum of her blended fur. He kneels, and with absolute tenderness, touches the ruff of her neck, which would be soft, were it not for the light tallowing of hairs.

What can be decided in a few moments that will not be questioned for a lifetime? He collects her coat from the nearby bushes. He moves to place it, gently, around her – she does not resist – and, his arms reaching cautiously under, he lifts her. The moderate weight of a mid-sized mammal. The scent of musk, gland, and faintly, faintly, her perfume – a dirty rose.

And still, in the woods and on the apron of grassland, no one is hiking, though soon there will be dogs tugging against leads, old couples, children gadding about. Down the path he walks, holding his fox. Her brightness escapes the coat at both ends; it is like trying to wrap fire. Her warmth against his chest is astonishing – for a wife who always felt the cold, in her hands and feet. She is calm; she does not struggle, and he bears her like a sacrifice, a forest pieta.

Half a mile in secret view. Past the sapling ash trees, through the heath gate, past the concrete pit where one sole girl is turning tricks on her board, practising before the boys come, her gaze held down over the front wheels. There are the houses – new builds, each spanking, chimneyless, their garages closed – and he must walk the gauntlet of suburbia, his heart founding a terrible rhythm at the thought of doors opening, blinds being lifted, exposure. Somewhere nearby a car door slams. She shifts in his arms and his grip tightens. Around the bend; he ignores the distracted neighbour who is moving a bin. Up the pathway to number 34. She is heavier now, deadening his muscles. He moves her to the crux of his left arm, reaches into his trouser pocket for the keys, fumbles, drops them, bends down. She, thinking he is releasing her perhaps, begins to wriggle and scramble towards the ground, but he keeps her held in his aching arm, he lifts the keys from the flagstones, opens the door and enters. He closes the door behind and all the world is shut out.