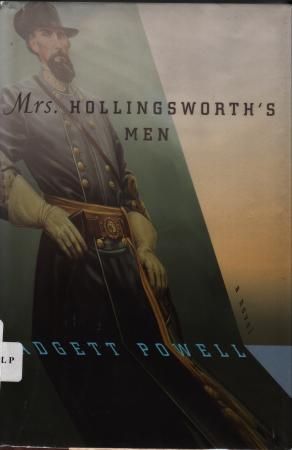

Mrs Hollingsworth's Men - Padgett Powell

Read Mrs Hollingsworth's Men - Padgett Powell Online

Authors: Padgett Powell

Mrs. Hollingsworth's Men

Padgett Powell

2000

For Nan Morrison

"After all, I think Forrest was the

most remarkable

man our Civil War produced?

—

General William Tecumseh Sherman

“

Forrest, . . .had he had the

advantages of a thorough

military education

and training, would have been the

great

central figure of the Civil War."

—

General

Joseph E. Johnston

“

Genera1 N. B. Forrest of Tennessee,

whom I have

never met,...accomplished more

with fewer troops

than any other officer on

either side."

—

General Robert E. Lee

Hollingsworth

Mrs. Hollingsworth likes to traipse. Her primary

worry is thinning hair, though this has not happened yet. She enjoys

a solidarity with fruit. She is wistful for the era in which hatboxes

proliferated, though a hatbox is not something even her grandmother

may have owned. More probably what she wants is hat boxes themselves,

without the era or the hats. But the proud, firm utility of the

hatbox requires a hat and an era for its dignity; otherwise it is a

relic. She does not want relics. Her husband is indistinct. She

regards friendly dogs with suspicion. Her daughters have lost touch

with her, or she with them, or both; it is the same thing, she

thinks, or it is not the same thing, which means it might as well be

the same thing: so much is pointless this way, indifferent, moot, or

mute, as a friend of hers says. Not a friend, but a friendly man whom

she cannot bring herself to correct when he says “mute" for

“moot," for then she might have to go on and indict his entire

presumption to teach at the community college, inspiring roomfuls of

college hopefuls to say "mute" for "moot" and

filling them with other malaprops, and if she indicts him on that

presumption she’ll need to go on and indict him for the presumption

of his smug liberalism and for affecting to like film as Art and not

movies as entertainment and for getting his political grooming from

the smug liberalism and film-as-Art throat clearing of National

Public Radio, and all of this, since it would be but the first strike

in taking on the entire army of modest Americans who believe

themselves superior to other Americans (but not to any foreigners,

except dictators) mostly by virtue of doing nothing but electing to

think themselves superior all of this would be unwise, or moot, and

indeed she may as well be mute, maybe the oaf was on to something.

She wanted to summon a plumber and pour something caustic down the

crack of his ass when he exposed it to her, as he invariably would

when assuming the plumbing position. Drano, she thought, tres

apropos. She had learned recently that the British term for the

propensity of the working man to expose himself in this way was

“showing builder’s bottom." That was a lovely touch of

noblesse oblige, of gently receding empire. She was less gentle in

her apprehension that the entire world and everyone in it was showing

its ass. She was not unaware, and not happy, that this apprehension

linked her closely to the film-as-Art side of the herd, and she would

go to a movie with a plumber wearing no pants at all before she’d

go to some noir with a man in slacks, but still she found herself

actually calculating the drift of things if one were to try to burn a

builder’s bottom. She figured on this seriously all one morning

until finally she faced it: it had come to this, had it? Her mind had

gone. The practical consequences of her symbolically telling the

world to pull its goddamn pants up filled up her otherwise empty head

at age fifty. It had all come to this. Muriatic acid for the driveway

contractor, liquid chlorine for the pool man, shot of Raid for the

bug man, upgrade the plumber to a bead of molten solder. When this

nonsense left her mind alone, she thought about the Civil War. How a

woman could be prevented from doing anything but thinking of

builder’s bottom, and of all which that represented, and of all her

impotence at reversing the disposition of the human world to show its

ass, was owing somehow to the Civil War. The American Civil War,

arguably as silly a war as they come, she was virtually ignorant of.

She was not better informed of any war, actually, save for perhaps

the Second World War and Vietnam, on a very topical basis. And she

knew of one man who had been in Korea. But the Civil War ... was

beginning to haunt her.

She could not reckon this sudden absorption with it,

given how vastly uninformed she was of it. Manassas was molasses,

Sharpsburg was Dullsville; the March to the Sea was no more than Hard

to Lee. Her images of the dead, which she did know to nearly exceed

the dead of all our other wars combined, were not those of the bodies

themselves that the wet-plate photography so in its infancy had

allegedly recorded in such stunning graphic detail. She kept seeing

not bodies but crows on them. To her, true torment was not death but

a crow.

The thousands of baleful tears shed then now went,

she thought, into laundry softener—the women threw these

handkerchiefs of the laundromat into their machines as they had

thrown kerchiefs at military parades. The result was every bit as

good: things smelled sweet and the women felt good about themselves.

Their men marched on in the perfume of goodfeeling and put their cell

phones to their heads and zeroed in on the enemy and fired nonsense

at him all day. They had learned from Vietnam how to drop smoke on

the enemy to target him better. There was much information. It was

not clear when everyone had stopped believing in himself.

A prison term was not the worst thing that could

obtain in this age, she thought. Nothing was. Nothing was the end of

the world. All could be surmised and survived. Death and rape were

just particularly bad. We were mature. But crows could land, after

all; they need not fly all day long. And you had to regard them.

She knew that the Confederate mint in Columbia had

printed its worthless millions and stood today in vacant ruin, but

virtually intact, for sale at too high a price to sell to whoever

would turn it into a museum or a mall. She knew that Appomattox is a

National Park, fully restored, visited by thousands of tourists a

year. She knew that only 4 percent of the final site of the Lost

Cause is original, based on the number of original bricks compared to

the total number of unoriginal bricks used in the restoration. She

knew that this restoration had had to commence from the very

archaeological digs that had discovered the outlines of the

foundation of the house where it all ended. None of the bricks was

even in its original location. Only some stones of the hearth are in

the same place. Beyond that, only the airspace is the original thing,

where it was. Maybe a piece of furniture or two that Grant and Lee

might have looked at. And she knew about Lee’s ingenious battle

orders that the Yankees found wrapped around dropped cigars. That

business amazed and frightened her. And the name Nathan Bedford

Forrest was in her head like the hook of a pop-radio tune. In her

grasp of it all, he was a man who had somehow never been beaten in a

war that was lost from the start. She knew more than she knew she

knew.

On her kitchen table she noticed an odd, tall can of

Ronson’s lighter fluid. There had not been a cigarette lighter of

the sort that required this fuel in this house in she would guess

twenty years. It would squirt down a builder’s bottom as pretty as

you please. She chuckled. She was not herself, she thought, or she

was, perhaps, and she chuckled again.

Were men who could not keep their pants up a function

of the Civil War? Were women who put up with them a function of the

Civil War? Was having yourself an indistinct husband a function of

the Civil War? Was finding a strange bottle of flammable petroleum

distillate beside your grocery list a function of the Civil War? Was

chuckling and not knowing what was yourself and what was not yourself

a function of the Civil War? Was not really caring at this point “who

you were," and finding the phrase itself a hint risible, a

function of the Civil War? She sat down at the table and wrote on her

grocery list, “A mule runs through Durham, on fire,” and then,

dissatisfied with merely that, sat down to augment the list.

Cornpone

Mrs. Hollingsworth wrote on:

A mule runs through Durham, on fire. No--there is

something on his back, on fire. Memaw gives chase, with a broom, with

which she attempts to whap out the fire on the mule. The mule keeps

running. The fire appears to be fueled by paper of some sort, in a

saddlebag or satchel tied on the mule. There is of course a measure

of presumption in crediting Memaw with trying to put out the fire; it

is difficult for the innocent witness to know that she is not just

beating the mule, or hoping to, and that the mule happens to be on

fire, and that that does not affect Memaw one way or another. But we

have it on private authority, our own, that Memaw is attempting to

save the paper, not gratuitously beating the mule, or even punitively

beating the mule. Memaw is not a mule beater.

The paper is Memaw’s money, perhaps (our private

authority accedes that this is likely), which money Pawpaw has

strapped onto his getaway mount, perhaps (our private authority

credits him with strapping the satchel on, but hesitates to

characterize his sitting the mule as he does as a deliberate,

intelligent attempt to actually “get away”); that is to say, we

are a little out on a limb when we call the mule, as we brazenly do,

the mount on which he hoped to get away, and might have, had he not,

as he sat on the plodding mule, carelessly dumped the lit contents of

the bowl of his corncob pipe over his shoulder into the satchel on

the mule’s back, thereby setting the fire and setting the mule into

a motion more vigorous than a plod. A mule in a motion more vigorous

than a plod with a fire on its back attracts more attention than etc.

Memaw, we have it on private authority, solid, was

initially, with her broom, after Pawpaw himself, before he set fire

to the satchel behind him, so the argument that Pawpaw might have

effected a clean getaway without the attention-getting extras of a

trotting mule on fire is somewhat compromised. Memaw, with her broom,

has merely changed course; she wants, now, to prevent her money’s

burning more than Pawpaw's leaving, though should Pawpaw get away

with the money unburnt, she presumably loses it all the same. That

loss, of unburnt money, might prove temporary: unburnt money is

recoverable sometimes, if the thieves are not vigilant of their

spoils, if the police are vigilant of their responsibilities, if good

citizens who find money are honest and return it, etc. But burnt

money is not recoverable, except in certain technical cases involving

banks and demonstrable currency destruction and mint regulations

allowing issue of new currency to replace the old, which cases Memaw

would be surprised to hear about. And it is arguable that were she

indeed whapping Pawpaw and not the fire behind him, her object might

be not to prevent his leaving but to accelerate it.

So Memaw is now whapping not the immediate person of

Pawpaw but the fire behind him. It is not to be determined whether

Pawpaw fully apprehends the situation. He may think Memaw’s

consistent failure to strike him with the broom is a function of her

undexterous skill with the broom used in this uncustomary manner. We

are unable, even with the considerable intelligence available from

our private authority, to hazard whether he knows the area to his

immediate rear is in flames. Why Memaw would prefer to extinguish the

fire rather than annul his escape or punish him for it is almost

certainly beyond the zone of his ken. We have this on solid private

authority, our own, our own army of private authority, in which we

hold considerable rank. Pawpaw is maintaining his seat, careful to

keep his clean corncob pipe from the reach of Memaw’s broom, errant

or not. Were the pipe to be knocked from his hand, either by a clean

swipe that lofts it into the woods or by a glancing blow that puts it

in the dirt at the mule’s hustling feet, he would dismount to

retrieve it and thereby quit his escape. It is likely that Memaw and

the burning mule would continue their fiery voyage, leaving him there

inspecting his pipe for damage.

The mule is an intellectual among mules, and probably

among the people around him, but we, the people around him,

intellectuals among people or not, as per our test scores, our

universities and degrees therefrom, and our disposition to observe

public broadcasting, and with the entire army of private authority we

command, cannot know what he knows. It is improbable that he knows of

Pawpaw’s betrayal, of Memaw’s hurt rage, of the accidental nature

of the fire, of the denominations of the currency, of the improbable

chance that among the money are dear letters to Memaw before she was

Memaw that she does not want Pawpaw to discover, even after he has

left her and might be presumed to be no longer jealous of her

romantic affairs. It is not certain that he, the mule, knows his

back, or something altogether too close to his back, is on fire. It

is certain, beyond articulated speculation, that he senses his back

is hot and that the kind of noise and the kinds of colors that make

him hot and nervous when he is too near them are on his back. He has

elected to flee, or is compelled to flee. Nervousness puts him in a

predisposition to flee. A woman with a broom, a two-legger with any

sort of prominent waving appendage, coming at him puts him in full

disposition to flee, which he does, which increases the unnerving

noises and colors and heat on his back, confirming him in the

rectitude of this course of action, notwithstanding certain arguments

that he has almost certainly never heard and might or might not

comprehend were he to hear them that he’d be better off standing

still.