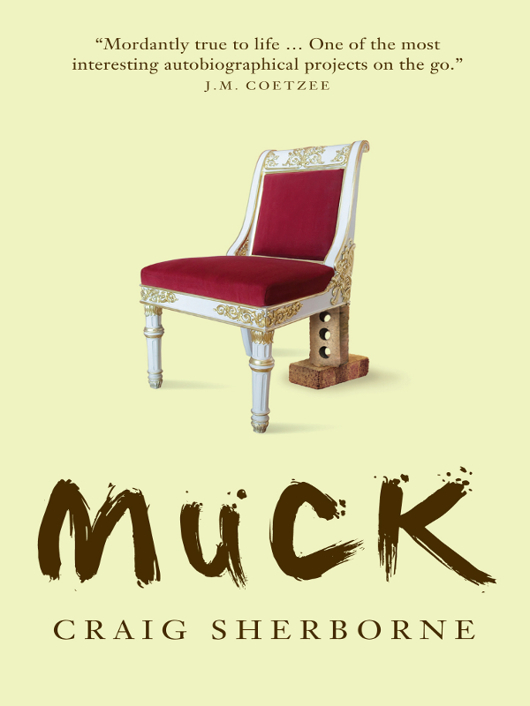

Muck

Praise for

Muck

:

“Excellent - it disturbs me to admit that Craig Sherborne goes deeper than the rest of us into the territory of impressionable immaturity. He writes beautifully, especially when the material is not beautiful at all. He can make the cruel truth poetic.”— C

LIVE

J

AMES

“Craig Sherborne’s daring, innovative prose is as exhilarating as his disciplined mastery of it is humbling. In service to an unnervingly sharp intelligence, it enlivens us to the comedy, the pathos, the dignity and the pain of life, as his characters live it.

Muck

is a masterpiece.”— R

AIMOND

G

AITA

“Mordantly true to life … One of the most interesting autobiographical projects on the go.” —J.M. C

OETZEE

“A work of searing originality and part of an ongoing masterpiece.”—P

ETER

C

RAVEN

,

The Monthly

“The prose is so taut as to be hieratic at times: one senses that the horror of what he has to tell is so great that, were he to relinquish his grip for even a moment, it would flare out and incinerate him.”—

Times Literary Supplement

“Riveting … Moral courage has propelled this book to the page. Its execution is sublime.”—

The Scotsman

Muck

CRAIG SHERBORNE

Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Media Pty Ltd

37-39 Langridge Street

Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia

email: [email protected]

http://www.blackincbooks.com

Copyright © Craig Sherborne 2011

First edition published by Black Inc. in 2007

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

e-ISBN: 9781921870286

I

F WE’RE ALL

born equal, why are some of us only cowboys?

I know why—an education.

Trackwork cowboys have no education. No wonder horse trainers mock them for such hard hands on a thoroughbred’s mouth, a sack of potatoes the way they flap-flop in the saddle. Listen to the foul-mouthed fucks and cunts of their cowboy cursing, the mongrel-bastards of their horse-hating though it’s dark dawn and no horse wants to walk faster so early.

They wear rodeo leg-chaps and Cuban heels. They put spurs out the backs of their feet like barbed wire. That’s the difference between types like them and people like me. My trousers are cream jodhpurs when I ride. My skullcap is black velvet with a black ribbon trailing behind. My boots go knee-high. They’re made of black leather, not gumboot rubber or fraying elastic sides. I’ve no spurs to stab with, I have a tongue to click-click up a rhythm.

They

kneel over their mounts as if they can’t do sitting. I have the straightest spine and join to the seat in my proper riding school way. I hold my hands down over the withers with reins threaded like so through finger and thumb. Like so over my pinkies to make a perfect U across the mane. My hips when I ride do little fuckings of the saddle and the horse rocks into me doing little fuckings back.

Cowboys. That’s all they’ll ever be, that’s all they ever amount to my father says and I have no reason to doubt him, I can see it with my own eyes, even in Sydney at Royal Rand-wick— Royal before the Randwick like a king of names. But in New Zealand you expect it. Here they have no Randwick racecourse with its kingly name and Bart Cummings calling out the riding orders not some simpleton farmer. In New Zealand when you amount to nothing the nothing must amount to less.

Yet in Taonga, Churchill gives himself airs as if a real race-day jockey. As if a man of style, not another

4

am cowboy. That polo-neck, I bet he bought it at an Op Shop. That anorak too, that polka-dot bandanna. His dented helmet droops on a slant, deliberately set at that angle to give him a look more debonair. How can he afford those Wee Willem cigars he’s smoking as though he were an important man?One on the way out to the sand track for a canter. One every three horses like the smell of bad wood burning. He may have a scissor-thin moustache but that just makes him old-looking, not distinguished for all its greying. He’s not distinguished and never will be in his life. He’s a cowboy. He will always walk with a worried man’s stoop. He is only here in Taonga because he did no good in England. If that wasn’t the reason, why didn’t he stay where he was born?

Taonga has only

3000

people but I have to admit those mountains are something—so higgledy with black-green forest and rockface when the cloud lifts from them by lunch. Forget the ugly mining truck tracks further to the south down Old Mana Road. Look at the mountains. They wall out the sky to the east. Somewhere deep inside them steamy artesian springs brew up and pour into the town’s public spas.

Dairy farms everywhere. Pastures so greeny lush that cows can run two to the acre, and milk leaves a going-stale smell on the air. But Churchill is no farmer. He rides horses for a living in that hunched-over cowboy way. If you call his five dollars a mount a living even if he gets through ten horses a day, which he can’t.

I know how much people earn. John, the manager of our liquor store in Rose Bay North, got $

300

a week and that was Australian. On top of that he got a cash bonus when we sold it, and could always help himself to a good-will gesture of supplies. Five dollars is a pittance—this is

1977

not the Dark Ages. Churchill mustn’t have had a good education even though he is English.

My father has the finest farm in all the district. Most farms in Taonga are only

100

acres, but ours is

300

. Ours milks

500

Jerseys and Friesians and needs a full-time staff of at least two, which is unheard of. It has enough grass left over from the cows for two broodmares, two yearlings and two foals. It can make an income of over $

80

,

000

if the manager’s modern, no peasant in his ways, no thinking cows are pets not money. That’s important because the farm is our main source of earnings. My father gambles on horses but gambling is just for play.

The lurks you get with farming, that’s the beauty of it. My father says “right on to the write offs” where his taxes are concerned. Lurks can bring your taxes down to forty cents in the dollar.

This place is why the liquor store was sold: what kind of legacy is a liquor store for a son! A father wants to pass on land. A father wants to create an estate and know that when he dies his son will have that same land under his feet. It’s a form of never dying. A dynasty will be born, from father to son, and son on to son and on it goes. A dynasty. Just like the families at that school I go to in Sydney. Though with us there’s a difference. At my school the farm boys are called Scrubbers because scrub is all there is west of the western suburbs say the Sydney boys, The Citys. When Scrubbers leave their grand boarding mansions to go home for holidays, they go home to drought and dust for all their owning

50

,

000

acres. What legacy is that to leave loved ones! What Scrubbers and their dustbowls earn our pretty sum!

Our

300

acres has rain on a string. Reach up and give a little tug on the air and the weekly watering will descend. Walk into a paddock and jump up and down. “Hear that?” my father whispers, putting his finger to his wide smile for me to shush and listen. “Hear it?”

Yes I hear it. Beneath our boots, beneath the very grass we stand on, the sound of water trickling like a brook.

When I tell Scrubbers about the water, about our

300

acres and

500

cows, the broodmares, yearlings, foals, they laugh at me to my face that I’m a liar—no

300

acres could feed

500

cows. That’s a backyard size compared to their vast thousands. It’s not something worth inheriting.

Because they all say it and none takes my side I worry that they’re right—I’m only one against a dozen. I worry: have I dreamed it, Taonga? Do I spend my days confusing dreams with the real things? No, I

have

seen it, and listened and smelt it for myself. I say to the Scrubbers how superior to theirs our land is. But still they laugh.