Murder and Mayhem (32 page)

Authors: D P Lyle

Everyone who dies should have a legally registered death certificate.

Regarding the terms you mentioned, you are not the only one who finds them confusing. Simply put, the "mode of death" refers to the pathophysiologic abnormality that led to death—for example, a cardiac arrest. The "cause of death" is what led to this abnormality, such as a gunshot wound to the heart. The "manner of death" is a legal, not a medical, statement and refers to whether the death was natural, a homicide, a suicide, or an accident.

The certificate contains the usual demographic information: name, address, age, sex, race, occupation, place of death (if known),

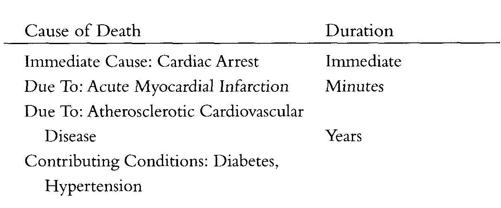

and information regarding the next of kin. The physician then adds the immediate cause of death (actually, this is often a combination of cause and mode—see, it is confusing) as well as conditions that led to or contributed to the stated cause and the duration that each of these was probably present. For example, in someone with high blood pressure and diabetes who suddenly fell dead from a heart attack, the physician might state the cause as follows:

He then signs and dates the certificate, making it official.

How Is the Time of Death Determined?

Q: How does the coroner determine the time of death?

A: Unless the death is witnessed, it is impossible to determine the exact time of death. The medical examiner can only estimate the time of demise. It is important to note that this estimated time can vary greatly from the legal time of death, which is the time recorded on the death certificate, and the physiologic time of death, which is when vital functions actually ceased.

The legal time of death is when the body was discovered or the time a doctor or other qualified person pronounced the victim dead. These may differ by days, weeks, or even months if the body is not found until well after physiologic death has occurred. For

example, if a serial killer kills a victim in July but the body is not discovered until October, the physiologic death took place in July, but the legal death is marked as October.

That said, the coroner can estimate the physiologic time of death with some degree of accuracy. He uses the changes that occur in the human body after death to help him in this endeavor. These changes consist of measuring the drop in body temperature, the degree of rigidity (rigor mortis), the degree of discoloration (livor mortis or lividity), the stage of body decomposition, and other factors.

Body temperature drops approximately 1.5 degrees per hour after death until it reaches the temperature of the environment. Obviously, this measure is greatly affected by the ambient temperature. A body in the snow in Minnesota in January and one in a Louisiana swamp in August will lose heat at widely divergent rates. These factors must be considered in any estimate of time of death.

Rigor mortis typically follows a predictable pattern. Rigidity begins in the small muscles of the face and neck and progresses downward to the larger muscles. This process of progressive rigidity takes about twelve hours. Then the process reverses itself, with rigidity being lost in the same fashion, beginning with the small muscles and progressing to the larger muscles. This phase takes another twelve to thirty-six hours. So rigor is useful only in the first forty-eight hours. After that the corpse is flaccid (limp), and the M.E. cannot determine if death occurred forty-eight or more hours earlier using this criterion alone.

The reason for the rigidity is the loss of adenosine triphosphate, or ATP, from the muscles. ATP is the compound that serves as energy for muscular activity, and its presence and stability depend on a steady supply of oxygen and nutrients, which are lost with the cessation of cardiac activity. As the supply of stable ATP declines, the muscles tend to contract, which produces the rigidity. The later loss of rigidity and the appearance of flaccidity (relaxation) of the muscles occur when the muscle tissue itself begins to break down.

As decomposition and putrefaction occur, the contractile components (the actin and myosin filaments within the muscles that are responsible for muscular contraction) decay, and the muscle loses its contractile properties and relaxes.

Lividity is caused by stagnation of blood in the vessels. It lends a purplish color to the tissues. The blood, following the dictates of gravity, seeps into the dependent parts of the body—along the back and buttocks of a victim who is supine after death. Initially, this discoloration can be shifted by rolling the body to a different position, but by six to eight hours it becomes fixed. If a body is found facedown but with fixed lividity along the back, then the body was moved at least six hours after death, but not earlier than three or four, or the lividity would have shifted to the newly dependent area.

At death the body begins to decompose. Bacteria begin to work on the tissues, and depending on ambient conditions, by twenty-four to forty-eight hours the smell of rotting flesh appears and the skin takes on a progressive greenish red color. By three days gas forms in the body cavities and beneath the skin, which may leak fluid and split. From there things get worse. Add to this the preda-tion by animals and insects, and the body can become completely skeletonized before long. In hot, humid climes this can happen in three or four weeks, sometimes less.

As you can see, this is a very inexact science and is greatly altered by the environment. In cold areas body temperature changes are magnified, but decomposition changes are slowed. The inverse is true for hot, humid climes.

Would Storing a Body in a Cold Room Hinder the Determination of Cause of Death?

Q: Is there a way that my character could try to cover up a crime of passion by cooling the body (in a wine room, perhaps) and then moving it but wind up with a pool of

blood when the corpse heats up in its new location? The crime occurs in the hot Arizona summer, if that makes a difference.

A: Actually, cooling the body would work against the killer by preserving the evidence. This is exactly what the coroner does when he stores a body in a refrigerated room until the autopsy can be performed. Cooling slows the process of decomposition and putrefaction. Gunshot wounds, knife wounds, and any poisons would be preserved longer and would make the coroner's job easier.

On the other hand, if the body was left outdoors in the heat, bacterial putrefaction would be greatly accelerated, so that by the time the body was discovered, tissue decomposition may be so far advanced that gun and knife wounds would be difficult to evaluate—that is, the depth and width of stab wounds and the characteristics of gunshot wounds that help determine how close the gun was to the victim, and so forth, would be lost in severely degraded tissues. If the decay was far advanced, even some poisons may no longer be detectable.

As for leaving a blood pool later, I'm afraid that won't work. Bleeding or oozing of blood requires that the heart still be pumping and the blood still circulating, which means that bleeding ceases at death. In fact, at death all the blood in the body clots very quickly, in a matter of minutes, and thus couldn't flow or ooze or drip and form a pool outside the body. Unlike ice cream, blood doesn't melt. Once it's clotted, it can't unclot.

This was brilliantly and subtly illustrated in the Coen brothers' 1984 film noir classic

Blood Simple.

The husband is shot as he sits behind his desk and is presumed dead. Later, another character comes in and sees the "corpse." The camera angles on the victim's hand, dangling above a pool of blood, and we see blood ooze down his fingers. At that moment the knowledgeable observer says, "Aha! He's not dead." Less clever viewers have to wait another scene or two to learn the same thing.

Can the Coroner Distinguish Between Electrocution and a Heart Attack as the Cause of Death?

Q: My victim is electrocuted while sailing by touching a boarding ladder that has been electrified, causing an apparent heart attack. Would there be any physical signs at autopsy that might show the victim died as a result of the electrocution rather than a heart attack? Skin surface burns, and so forth?

A: The autopsy findings depend on the amount of voltage applied. If the voltage was high, burn marks would be left at the points of contact and grounding—that is, the entry and exit points of the current. These would be readily identifiable by the medical examiner. Also, when a strong electrical current flows through the body, it damages (cooks) everything in its path, and these effects can be seen when the various tissues are examined microscopically. This is particularly true of the liver, which seems to be prone to this type of injury.

If the voltage was low, no skin changes would occur. And to be puristic, in this situation the victim wouldn't die from a heart attack (myocardial infarction, or MI). In its true and simplest definition an MI means that a coronary artery (the arteries that course over the surface of the heart and supply blood to the heart muscle) became blocked, and a portion of the heart dies due to lack of blood supply. In a true MI the M.E. would find the blocked artery and the damage to the heart muscle. An electric current could not directly cause this.

Though a lower-voltage electrical shock would not cause heart muscle damage, it could precipitate a lethal change in heart rhythm, such as ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation. These could only be diagnosed if an electrocardiogram (EKG) was

connected to the victim at the time the arrhythmias occurred. This is unlikely in the case you present.

At autopsy the heart would likely appear normal in this circumstance, so the electric shock would not be detectable. With no MI and no skin burns, the M.E. would probably assume the victim died of a cardiac arrhythmia, which, of course, is exactly what happened.

As you would expect, a voltage between these two would yield mixed results.

Can the M.E. Distinguish Between Blunt Trauma and Stab Wounds as the Cause of Death?

Q: My victim is a young female in the very early stages of pregnancy The perp is furious about the baby and strikes her in the abdomen. My theory is that this would probably not be sufficient to induce a miscarriage but would definitely leave evidence for the M.E. Right?

Thrown off balance, the victim falls and strikes her head on the edge of the bathtub. Would there be any clue as to what surface specifically caused the injury? Even without an indication of what caused the head injury, would there be some indication that this injury occurred prior to the fatal wounds? For plot purposes I'd like the unconscious victim to be moved elsewhere as a diversion, where multiple stab wounds would be inflicted as the ultimate cause of death.

The murder occurs on a summer night in Arizona, and the body is not discovered until the next day. Would the M.E. be able to determine the true cause of death?

A: The blow to the abdomen could or could not cause a miscarriage. If the force was strong enough and applied directly to the

lower abdomen, it could damage the fetus, the placenta, or the uterus severely enough that the fetus would no longer be viable and a miscarriage would result. Or the blow could simply contuse (bruise) the abdominal wall. Your call, since either is possible.

The M.E. would likely see the contusion, unless the victim was killed only a few minutes after the blow. Bruises take a few minutes to appear. He would be able to tell that the blow was applied ante-mortem (before death) by the gross and microscopic nature of the contusion. Bruising results from a leakage of blood from injured microscopic capillaries and requires that blood flow, and therefore life, be present. After death the blood clots in a few minutes so that this leakage no longer occurs. Postmortem (after death) blows would not produce bruising.

The fall against the tub could be lethal or merely knock her unconscious (a concussion), as you proposed. The M.E. would be able to tell that this injury also was antemortem, and he might be able to ascertain the general shape of the object. Bathtub edge? Baseball bat? Metal pipe? Unless the enamel coating of the tub cracked and small pieces clung to her hair or skin, he probably wouldn't be able to go beyond guessing the general shape of the object.

One day in the desert wouldn't destroy much of the forensic evidence unless predators dismantled, consumed, and scattered the body. The M.E. would be able to determine that the cause of death was multiple stab wounds and that the other injuries were ante-mortem but not the proximate cause of death. He could, of course, determine that she was pregnant. And if a miscarriage occurred at the time of the beating, he would be able to determine that also.