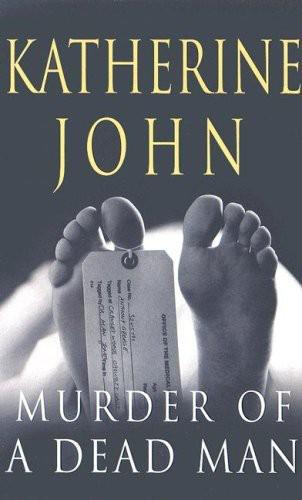

Murder of a Dead Man

MURDER OF A DEAD MAN

Katherine John

Book 3 in the Trevor Joseph series

MURDER OF A DEAD MAN

First published by Hodder Headline 1995

This edition revised and updated by the author Copyright © 2006 Katherine John

published by Accent Press 2006

ISBN 1905170289

The right of Katherine John to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission from the publisher: Accent Press, PO Box 50, Pembroke Dock, Pembs. SA72 6WY

Printed and bound in the UK

By Cox and Wyman Ltd, Reading

Cover design by Emma Barnes

The publisher acknowledges the financial support of the Welsh Books Council

FOR ROSS MICHAEL WATKINS.

- DEDICATION

- PROLOGUE

- CHAPTER ONE

- CHAPTER TWO

- CHAPTER THREE

- CHAPTER FOUR

- CHAPTER FIVE

- CHAPTER SIX

- CHAPTER SEVEN

- CHAPTER EIGHT

- CHAPTER NINE

- CHAPTER TEN

- CHAPTER ELEVEN

- CHAPTER TWELVE

- CHAPTER THIRTEEN

- CHAPTER FOURTEEN

- CHAPTER FIFTEEN

- CHAPTER SIXTEEN

- CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

- CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

- CHAPTER NINETEEN

- EPILOGUE

A chill hush pervaded the basement of the General Hospital. Someone standing close to the lift shaft or to the staircase leading down into the entrails of the building might hear the distant hum of the boiler that fed scalding water into the heating system. The boiler worked well; too well. The temperature on the wards rarely dropped to a tolerable level.

The muffled clanking of a trolley being wheeled into an elevator, followed by the remote clatter of equipment, reverberated through the stairwells, but the sounds only served to remind that the bustle of hospital life had no place down here.

Even the corridors that led out from the brilliantly lit, white-tiled hall that covered three quarters of the floor area were deserted, stretching emptily into blind, secretive corners.

When night fell, even seasoned staff accustomed to death’s presence on the wards avoided the passages that led down to the steel double doors below ground level. Behind them were stowed the General’s failures. The patients who’d succumbed despite the care, skill, and technological advances.

A young man with the unhealthy pallor of someone rarely exposed to the sun bent over a trolley. His hair fell forward, covering his face, his spectacles slipped, and his hands trembled as he concentrated on the task in hand. And while he worked, the powerful lamp set low overhead burned, stinging his eyes and searing his neck.

He paused and glanced nervously over his shoulder. Shaking his head at his foolishness, he flexed his rubber clad fingers before resuming his kneading of the stomach of the cadaver he was laying out. He had watched the procedure often, knowing his turn would come, but never thinking that it would come so soon. That Jim would call in sick tonight.

They usually spent the greater part of their night shift in the porters’ station, drinking tea and scanning old copies of

Playboy

. But not tonight. It was only half past two but there had been three deaths already and two calls from the wards warning of more to come.

Clenching his fists, he pressed down hard. Air wafted from the corpse’s open mouth. It lingered in the chill, bright air, a final sigh that made the attendant’s blood run cold. He pushed down again trying not to look at the face or think of the man this had been. The tags attached to the wrist and ankles detailed a name and number, but he remembered only the age. Twenty-seven – born the same month and year as him. Even the casualty sister had been affected by the tragedy of such an early death.

Why hadn’t he given a thought to his future when he had opted to read philosophy? If he’d studied accountancy or law he would be equipped for a profession. He wouldn’t be here, in this ceramic and steel house of the dead. A repository where corpses were stowed, until the ceremonies were over and they could be forgotten.

He flinched when the telephone shrilled.

Peeling off one rubber glove he left the corpse and picked up the receiver.

‘Mortuary!’

‘Ward Eleven. We need you immediately.’

‘Can’t you get a porter, I’m laying out.’

‘No porters available.’

‘A nurse.’

‘We’re short staffed. Down to two on the ward.’

‘I’m working single handed.’

‘We all have our problems. It’s an old lady in a four-bedded ward. People are awake. It’s upsetting them.’

‘I’ll be there.’

He replaced the receiver and returned to the corpse he was laying out. The body was flat, legs straight, arms parallel to the body. The eyes were closed, but not the mouth. He taped the jaw, and as he did so, looked at the face for the first time. The features were regular, even. The kind his girlfriend admired when she wanted to tease. The man had been tall, over six feet, with thick, dark hair. What wouldn’t he have given to have had hair like that?

His had always been thin, and was now receding. He pulled off the second glove, tossed it into a bin and picked up a fresh pair from the box. There wasn’t anything so pressing that couldn’t wait the quarter of an hour it would take him to go to Ward Eleven.

The sheet he picked up rustled as he draped it over the corpse. It was silly of him to bother but he didn’t want to be faced with the uncovered body on his return. Dark hair, pale skin; so lifelike and so dead.

He pulled an empty trolley from a rank lined against the wall and wheeled it into the corridor.

Regulations demanded that the mortuary be manned at all times, or else locked. He’d read his contract and signed it but it hadn’t taken him long to discover working practices were very different from rule book ordinances. He had not forgotten the terms of his contract, simply learned to ignore them, as did the other attendants and porters. There was often no option since the place was understaffed. Besides, it would be a bind to have to dig his keys out of his pocket and lock the door when he would only to have to repeat the procedure on his return.

The nurse had said there were other patients awake, so he’d chosen one of the new American-style carts. The body was deposited in a box-like hollow and a lid dropped down to cover it. Then a sheet was placed over the box. Simple, but effective.

A flat sheet didn’t draw the curious stares a shrouded corpse attracted, but the box carts never fooled a patient who’d witnessed the disappearing act.

He recalled the nurse saying, “It’s upsetting them.” Upsetting who? The staff? The patients?

Visitors? – Of course visitors. Ward Eleven always had relatives staying over. Sitting by the beds, pacing the corridors, waiting for the end to come.

And it nearly always came during the hours of darkness. Or did it just seem that way?

He reached the lift, parked the trolley and pushed the button for the eighth floor. He didn’t have to wait long. The elevator ran smoothly to the seventh floor then shuddered violently, finally jerking to a halt on the eighth.

‘You took your time.’

‘I came as quickly as I could. I’m the only attendant on duty tonight.’

‘This way.’ The staff nurse marched ahead of him. He’d been right about the relatives. A woman stalked them, an anxious frown creasing her face.

‘Staff…’

‘I’ll be with you in a moment. Here.’ She pushed open the door to a small ward. The curtains were drawn around the bed nearest the door. He wheeled his trolley through the gap bumping into a student nurse who was dismantling a drip. She looked up, her eyes heavy from lack of sleep. He opened the box on the trolley.

‘She was a dear,’ the student whispered. ‘Never complained.’

As she helped him lift the emaciated, slack-jawed figure from the bed on to the trolley he made a decision. Tomorrow – he wouldn’t go to bed right away, he’d shower, change, take a walk to the Job Centre and look at the boards. If there was nothing there, he’d buy a paper and go through the situations vacant column. There had to be something better than this.

‘Thanks. I’ll take it from here.’ He reassembled the box, and straightened the sheet ensuring the folds hung down, obscuring most of the trolley. The staff nurse nodded to him as he returned to the lift.

The woman he’d seen earlier turned her back as he passed. He saw the look on her face and wondered if the extra the hospital had paid for the wagons had been worth it.

The lift was still on the eighth floor. There wasn’t much call for movement between wards in the early hours. He pressed the button, opened the doors and wheeled in his load. The juddering was repeated as he descended into the basement. The door opened on to the deserted corridor.

He pushed the trolley towards the mortuary.

Halting in front of the door, he looked around. He had no reason to do so. There had been no sound, nothing to alert him to the presence of anything untoward. Only a feeling of unease.

He took a deep breath. He was a grown man, a philosophy graduate. There was nothing to fear down here. As Jim had put it. “Our clients may not be happy with their lot, but you’ll never know any different. You won’t get a peep out of them.” He pushed the front end of the trolley through the doors. Then he froze.

The young man’s corpse was sitting bolt upright on its trolley, facing him, the sheet draped in folds around the waist.

Jim had warned him that it could happen if all the air wasn’t expressed from the stomach. But he was too horror-struck to wonder about the reason.

The torso facing him was white and finely muscled, with a mat of dark hair on the chest. But the porcelain gleam of the chest was in glaring contrast to the bloody, purple-blue pulp where the face had been. Only the eyes remained. The irises dark, the whites bleached, staring out above scraped cheek bones. Below, teeth grinned in a lipless aperture.

He continued to gaze, mesmerised, registering stumps where the ears should have been, black holes between the eyes where the nose and nostrils had been torn away. The ragged hairline above the naked cranium. One word echoed through his mind as the scream finally tore from inside his throat.

Flayed!

The face had been skinned as neatly and completely as his father had skinned the rabbits he’d shot on their farm back home. But why would anyone want to skin a dead man?

‘Two, four, six, eight, who do we want to date – turn

– jump – hop – scotch –’ The young girl balanced on one leg before swooping down and retrieving a flat piece of marble from one of the squares painted on the surface of the playground. Placing it next to her foot she hopped, sending it skidding further down the geometric pattern of white on black tarmac.

‘It’s my turn after Hannah.’ A plump child elbowed her way aggressively to the front of the queue of girls.

‘No it’s not!’ The girl who had possession of the hop-scotch hovered, one foot in mid-air. ‘It’s Kelly’s.’

‘So there, Miss Bossy Boots.’ The girl who’d been elbowed aside reclaimed her place.

The children’s voices, eager, high pitched, carried across the school yard, out through the railings to an alleyway where a painfully thin man lurked, watching their game. His face was grimy with ingrained dirt, his chin black with stubble, his shoulder-length hair matted. A rusty black overcoat flapped at his knees, revealing ragged trousers stiff with grease. The only splash of colour was in his shoes, bright red baseball boots with luminous blue laces.

He shrugged his shoulders, easing the weight of the knapsack he was carrying. His eyes, keen, feverish, watched every move the young girl on the hop-scotch made. She was an attractive child. Tall for a junior school pupil, slender, with none of the puppy fat that characterised her playmates. Her silver-blonde hair was brushed away from her face and plaited into a ripple that extended to her waist.

Her eyes were blue, a deep cornflower blue that shone like painted enamel in the drab surroundings of the school yard. She was easily the prettiest girl in the group. A swan in a sea of ugly ducklings. The grace and beauty of the woman yet to emerge could already be seen in her willowy figure.

‘Miss! A dirty old man is watching us.’

The voice was shrill, the speaker a small boy who sat apart from the others at the foot of the railings. A middle-aged woman wearing a grey woollen dress and a lumpy, home-knitted blue jacket dashed towards the gate from the other side of the yard. Games were abandoned as all the children within earshot turned and looked into the alley. The man ran off.

‘That’s my Daddy!’ Abandoning the precious stone that entitled her to first turn of every game, Hannah tossed her plait over her shoulder and darted out of the playground before the middle-aged woman could reach, let alone stop, her. She bolted across the narrow road without giving a thought to traffic. The squeal of brakes was followed by the muffled curses of a driver.