Murder on Bamboo Lane

Read Murder on Bamboo Lane Online

Authors: Naomi Hirahara

PRAISE FOR

MURDER ON BAMBOO LANE

“A heartfelt new crime novel with a likable heroine and a unique, street-level view of Los Angeles. In a genre inundated with angst-ridden cops and eccentric geniuses, LAPD bicycle patrol officer Ellie Rush is a refreshing change—one of the warmest, most realistic characters to hit crime fiction in a long time. Hirahara’s affection for Los Angeles, and for the intricate, multicultural mix of people who inhabit it, comes through on every page.”

—Lee Goldberg,

New York Times

bestselling

coauthor of

The Heist

“Officer Ellie Rush is smart, funny, observant, a good friend, a dutiful relative, and a compelling character whom you want to get to know better.

Murder on Bamboo Lane

delivers seamless writing, interesting characters, the right touch of romance, social commentary . . . the list goes on.”

—Sheila Connolly,

New York Times

bestselling author of

the County Cork Mysteries

“[A] fresh, funny, and fascinating mystery. Young bicycle cop Ellie Rush might be the opposite of hardboiled, but she’s courageous, clever, and can wind her way through the back streets of LA to the best ramen shops. The most original mystery I’ve encountered in many years—

kampai

to Naomi Hirahara for a terrific new series.”

—Sujata Massey, author of

The Sleeping Dictionary

and

the Rei Shimura Mysteries

“A great series opener! Ellie Rush, a Japanese American LAPD rookie, is smart and tough as she investigates a Chinatown murder. Edgar® Award–winning author Naomi Hirahara paints a mesmerizing portrait of the Los Angeles she knows so well, a city where being Asian American evokes a long history of racism and violence. If you liked her Mas Arai series, you will LOVE this!”

—Henry Chang, author of

Chinatown Beat

“What a debut! Naomi Hirahara’s new series, featuring LAPD rookie Ellie Rush, is a total home run, a crackling mystery featuring a character who has strength, brains, and yards and yards of heart. I love this book!”

—Timothy Hallinan, Edgar

®

-nominated author of

the Poke Rafferty and Junior Bender mysteries

“Insightful into the twists and turns of the human psyche and the enclaves of the vast Southland . . . Hirahara delivers the goods in this first of what one hopes will be many mysteries involving bicycle officer Ellie Rush.”

—Gary Phillips, author of

Warlord of Willow Ridge

“Hirahara takes us inside two cultures closed to most of us: the Japanese American family and the LAPD. What I love about this book is the complete lack of sappy sentimentality about the one or hero worship about the other. From the first page, Ellie Rush and her world seemed real to me and I was glad for every moment I spent there.”

—SJ Rozan, author (as Sam Cabot) of

Blood of the Lamb

“The ingenious idea behind Naomi Hirahara’s new novel—bike cop as sleuth—allows her to navigate LA’s mean streets in a whole new way and plunges us viscerally into the city’s colorful neighborhoods . . . Hirahara’s

Murder on Bamboo Lane

brims with authenticity about city politics, ethnic identity, police banter and family dynamics . . . Ellie Rush is a wonderful new protagonist, the plot is gripping and the book is a winner.”

—Denise Hamilton, author of

Damage Control

and editor of

the Edgar

®

Award–winning anthology

Los Angeles Noir

THE BERKLEY PUBLISHING GROUP

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014

USA • Canada • UK • Ireland • Australia • New Zealand • India • South Africa • China

A Penguin Random House Company

MURDER ON BAMBOO LANE

A Berkley Prime Crime Book / published by arrangement with the author

Copyright © 2014 by Naomi Hirahara.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Berkley Prime Crime Books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group.

BERKLEY® PRIME CRIME and the PRIME CRIME logo are trademarks of Penguin Group (USA) LLC.

For information, address: The Berkley Publishing Group,

a division of Penguin Group (USA) LLC,

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014.

eBook ISBN: 978-1-101-60945-3

PUBLISHING HISTORY

Berkley Prime Crime mass-market edition / April 2014

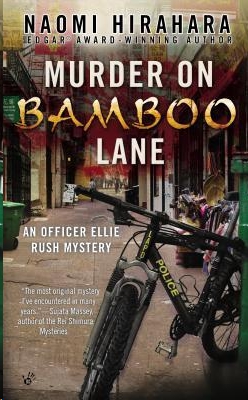

Cover illustration by Dominick Finelle (The July Group).

Cover design by Jason Gill.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

For Melissa and Chloe

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The character of Officer Ellie Rush was created through the crossing of many seemingly unrelated paths. Thanks to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, ATF Los Angeles Field Division Citizens’ Academy (then organized by Agent Christian Hoffman) for teaching me the value of teamwork in law enforcement; the decennial Census Partnership team for introducing me to parts of Los Angeles that I never knew; the students of the UCLA Asian American Studies creative writing class for inspiring me with their enthusiasm and intelligence; and the California Forensic Science Institute, under the direction of Rose Ochi, for exposing me to the perils of report writing.

Author and former LAPD officer Kathy Bennett gave me some advice on a few police terms, while Bruce Krell of Shooters-Edge attempted to increase my knowledge of firearms; any possible errors are completely mine.

My agent at Gersh, Allison Cohen, helped hone plotlines as well as find a home for Ellie. Heavy editorial lifting was done by the ever intrepid Shannon Jamieson Vazquez. Much appreciation to the rest of the Berkley Prime Crime team, including copyeditor Andy Ball.

And finally, of course, love and thanks to my husband, Wes, who always reminds me what’s really important in life. And welcome, Tulo, to our household, just in the nick of time!

SOUTH FIGUEROA STREET

My first piece of advice: If you ever get lost in Los Angeles, don’t ask a blonde for directions. Ask someone like me. No offense. I’m not making a dumb blonde joke, really. My friends who are women’s studies majors at my old college, Pan Pacific West, would have my head on a platter for saying anything so un-PC. But while people sing about California girls with their golden hair, we natives know the truth: that most of us have either dark hair and/or dark skin. And we usually know where we’re going.

Technically, though, I am white, or at least part white. My dad is white, while my mother is Japanese American. With the plain, old English last name Rush and my pale skin color, I “pass”—but in my line of work, “passing” can actually be a liability.

At my first public event representing “the face of the LAPD” when I was still on probation, people had no idea what to make of me. “What does this white girl know about our neighborhood?” “What is she, sixteen?” A few rows back, against the screeching of folding chairs being rearranged, the same things were said in a staccato of Spanish, effectively shooting holes through my reputation. Why be insulted in one language when you could be in two?

I’d wanted to whip around, and say,

Listen, I’m not only white, I’m also Asian, and my grandparents and great-grandparents lived around here since before World War Two

. I could have also repeated pretty much the same thing in Spanish, my major in college before I joined the LAPD. But I wouldn’t have said anything about my age; I’d been just about to turn twenty-two at the time, which probably wouldn’t actually have impressed them.

That was about a year ago, and since last December I’ve been patrolling the southern area of the Central Division five days a week via an LAPD-issue bicycle. If this were a Hallmark television movie, by now I’d be winning over each of my constituents one person at a time. Unfortunately, this is real life.

“Officer Rush, Officer Rush!” I’m tempted to ignore the familiar voice and keep riding north up Figueroa Street. Instead, I ease down on the brake and come to a stop. I turn back from my bicycle toward the sidewalk.

“Officer Rush, I have something to show you.” Mrs. Clark, president of the local neighborhood watch, is wearing a velour sweatshirt decorated with rhinestones outlining a winged heart. Huge sunglasses are perched on her head over her relaxed hair.

“Hello, Mrs. Clark,” I say when she’s finally by my side.

“I want you to look at this. Last night, some fool dropped some flyers all over every light pole and business gate. And then it rained, so now look at this sopping mess. This is littering—flyer pollution—pure and simple.”

As a P2, Police Officer II, just fresh off of probation, I’m supposed to be some kind of goodwill ambassador. What that usually means is listening to complaints. Complaints about a neighbor’s dog, a neighbor’s kid, a neighbor’s boyfriend. I go to these neighborhood watch meetings at least once a month, only to find out that people are not too neighborly.

At the last neighborhood watch meeting, for example, the posting of flyers on public places was discussed for forty-three minutes. I know exactly because I timed it. I soon figured out that the problem was more about black (old-timers) versus brown (newcomers), English versus Spanish.

I didn’t see how this flyer issue was LAPD business. I told them to file a complaint with the City Department of Public Works, but they knew I was just giving them the old runaround. They had apparently seen it before. Many times before.

Still, I know Mrs. Clark wants to just clean up her neighborhood and make it safe for her grandchildren and their friends. I take a copy of the flyer, damp from last night’s drizzle.

I’m surprised I hadn’t noticed it earlier.

It’s a familiar face. A photo of an Asian woman, about my age, with sharp angles to her face. She’s pretty, very pretty, but she’s not smiling. She’s wearing a Pan Pacific West College T-shirt. I have the same one somewhere, smashed in the corner of my closet underneath a plastic laundry basket.

Below her photo is the word

MISSING

, and her name, Jenny Nguyen. I do a double take on the e-mail address listed as a contact. I know that e-mail address. On the other side, the same thing, only in Spanish.

Mrs. Clark waits for me to comment.

“At least it’s in English, too,” is all I can offer her.

She makes a face and leaves my side. For a hot second, I think about contacting that e-mail address, but I catch myself. I have to follow police protocol. I’m not Ellie Rush, friend and college classmate, right now. No, I’m a full-time employee of the LAPD.

• • •

As I ride in to Central Division to turn in a couple of reports and clock out, my tires bounce over mounds of congealed trash. The day after a rainstorm in LA: spic-and-span for cars, but a totally different story for bicyclists. Whatever was left in the middle of the street is now pushed out to the sides in the bicycle lanes and gutters.

Our squad room is totally old school. It looks like the cardboard sets on the television police dramas my father likes to watch. My college library had better computer equipment than we do here, but we make do.

Before I can get my helmet off and enter the building, I hear a hissing at my side. It’s Detective Harrington. Pieces of orange hair, like strands of saffron, stick out awkwardly from the same haircut he’s probably had since the 1970s. He should be on his way to retirement, but he hangs on because he’s supporting not only his kids but his grandkids, too. “Do you have it?” He shields his eyes, almost as if he’s making a drug deal.

“My locker,” I tell him. He waits outside because he’s technically off duty. It takes me about fifteen minutes to mount my bike on the wall rack, get what he needs and bring it outside.

I hand him the folder that contains the arrest report for a case of a suspect resisting arrest with violence. It needed work, but not as much as some of his earlier ones. Harrington is a good cop but not a great writer. He’s the king of run-on sentences and paragraphs, and his organization is usually out of whack. In this latest report, he failed to explain how the suspect was made aware that Harrington was a police officer—a crucial piece of information for a jury trial.

As I go over the report with my edit marks, I know why Harrington trusts me to help him out like this: I’m a lot younger. A woman. I seem safe. Maybe he looks at me as a favorite granddaughter—or a secretary. Either way, what he definitely doesn’t realize is that my aunt is Assistant Chief Cheryl Toma, the highest-ranking Asian American in the LAPD.

Thanking me, he tries to give me a twenty, and I shake my head. “I’ll need your advice sometime,” I say.

Advice about making detective

. But I don’t add that part. Somehow it seems embarrassing to mention that ambition out loud, barely a year and a few months out of the academy.

Harrington takes off, and I go back inside. My archenemy, Mac Lambert, is there. He looks completely normal—sandy-colored hair trimmed short, medium build and height, wearing the same uniform I am, a LAPD-issue black shirt and shorts—but don’t let that fool you. He’s a first-class a-hole.

He’s only a P2 like me, even though he’s been in the department for at least five years. He’s not my supervisor, but he acts like he is. Like right now, he glares at me as if I’m late for an appointment, and says, “Rush, meeting,” and gestures toward the squad room.

No one told me about a meeting

, I want to say, but I keep my mouth shut.

Apparently the unscheduled meeting has already started. I pull up a seat next to Johnny, who was in Bicycle Patrol School with me. Our bike liaison, Jorge, is speaking. I’m able to quickly figure out what’s going on. There’s been another accident involving a bicyclist on Flower Street.

By its name, Flower Street sounds very picturesque, but it’s anything but. During rush hour, it’s like a current of cars that hardly ever stops. Law firms are everywhere on this one-way street traveling south. If Flower Street ever collapses into a sinkhole, it probably will take half of our city’s attorneys with them. (I know some people who would have no problem with that.)

“Today’s incident was with a janitor who just got off of work,” Jorge says. I’m surprised. The last one was with a bike messenger who was weaving in and out of lanes. He wasn’t entirely blameless. “We had to close one lane for forty minutes.”

Captain Randle interrupts for a moment. “People, we’re talking about gridlock. We can’t have gridlock on Flower in the middle of the day.” I know what Captain Randle is really saying. Street closure means that lawyers are losing money. We can’t piss the lawyers off. Or our councilman, Wade Beachum.

Our liaison nods. He is so totally clean-cut that his forehead even shines in the fluorescent light. Jorge is supposed to help us improve relations with special-interest groups. Bike clubs and eco green groups haven’t been the biggest fans of the LAPD, at least in the past. I can’t imagine Jorge, with his shiny forehead and crew cut, sitting down with hippies and hipsters with unkempt hair and hemp-based clothing, but he’s apparently good at what he does.

You wouldn’t think of LA, with our well-known obsession with cars, to be a center for bicyclists, but it slowly is becoming one. It all started with our former mayor, a cyclist himself, who broke his elbow after falling off his bike when a taxi abruptly pulled in front of him. Nowadays, in downtown alone, the major thoroughfares—including Main, Spring, Olive and Grand—all have dedicated bike lanes. Bicyclists even take over Downtown LA a few days a year, like for our CicLAvia—a riff on carless events that apparently started in Latin America—or for professional races, in which hundreds of riders burn the asphalt at thirty miles an hour.

What Jorge is telling us is basic. We’ve heard it all before: Go out and speak to our contacts with bike messenger companies. Hold more bike safety workshops, and make sure that they are offered in other languages besides English. It’s toward the end of our shift, so no one really seems to be listening. I’m thinking about the truant citations I still need to file. Twenty-one of them—kids who, for the most part, I’ve dealt with before. Hardly anyone else in the LAPD or even the school district police district issues truant tickets anymore. The principal of the local school publicly rails against criminalizing truant students but privately asks me to go after them because attendance has been dropping. And where there’s no students, there’s no money.

The one I’m most disappointed to see ditching school is Ramon, a good kid I know from my ex-boyfriend Benjamin’s tutoring program. He’s had a tough life—his father is dead and his mother is in jail. Even so, it’s only now, under his aunt’s care, that he’s been living in the same place for more than one year.

Ramon and I are both dog lovers, maybe the only thing we have in common. I have Shippo, the fattest white Chihuahua mix in the world, and when Ramon’s not in school, he’s usually out walking with his beautiful pit bull, Romeo. When I asked him about Romeo today, though, his face fell. Something’s happened to Romeo that Ramon didn’t want to talk about. No Romeo equals no conversation.

The meeting finally ends, and we all get out of our seats. All of us, that is, except me. Someone is blocking my way.

“So, Rush.” Mac, who holds a clipboard, is working with our assistant watch commander on assignments for special-events patrols. Tomorrow begins the Chinese New Year parade festivities, and I prepare myself for the lousy assignment I’m going to be given.

“Yes?” My back stiffens. For the past three festivals, I’ve had to circle porta-potties, and I know that a line of twenty-five porta-potties has been installed on North Broadway on the edge of Chinatown.

“For the parade, I have you just east of North Broadway, by the park.”

I let out a small sigh of annoyance, then think,

Oh my God, did I really just do that?

“What, you have a problem?”

“No,” I say. I have no idea why Mac’s assigned to the bicycle unit. I had heard from Harrington that Mac was on the fast track for a promotion until something went wrong. He doesn’t like it here, that’s for sure. But why does he have to take it out on me?

Sergeant Tim Cherniss, who

is

my supervisor, comes around, saving me from Mac. He asks how my day went, and I show him the flyer with Jenny’s face. “I know her,” I tell him. “I’d see her on campus when I was going to PPW.” I’m aware that Mac is still standing next to me. Doesn’t he have more assignments to give out to other people? “That contact e-mail address? It’s my friend’s.”

“Well, see if a missing-person report was filed. That’s about the most you can do,” Tim says. “A lot of times they’re on the run from their families, boyfriends, creditors. Sometimes they just want a fresh start. As you know, being missing is not a crime.”

I nod my head. “Yes, I’m sure she’ll turn up,” I say, but my voice doesn’t sound sure at all.

• • •

“Mac’s really messing with my head.” I take another swig of my Sapporo. The bottle’s lip feels cool against mine and, for a minute, I miss my ex-boyfriend. I guess it’s been too long.

“Fu—forget about him,” my best friend, Nay Pram, says. Her mom, with whom she lives, has been on her case for using four-letter words too much, so Nay’s been trying to clean up her vocab. She claims that her mother does her share of swearing in Khmer, and that it’s a lousy double standard. Then I remind Nay who’s paying the rent, and she tells me to pinch her every time she swears. But whenever I pinch her, she swears, so then I have to pinch her again.

Nay and I have been best friends since we were in the same American studies class freshman year. She came in late and stumbled into the first available seat, which happened to be next to me. She, of course, didn’t have a pen handy—yes, I had an extra—needed notes of what had happened—yes, I’d e-mail her mine—and last of all, wanted to take me out for coffee—oops, forgot her wallet. That pretty much sums up our relationship for the past five years, except that I know she’d pretty much kill anyone to save my life.

We sit at our usual place, Osaka’s, the ramen house on First Street in Little Tokyo. Nay’s drinking a Diet Coke, also as usual. Not because she’s trying to lose weight (well, to be honest, she could lose a few pounds), but because she actually likes the taste.