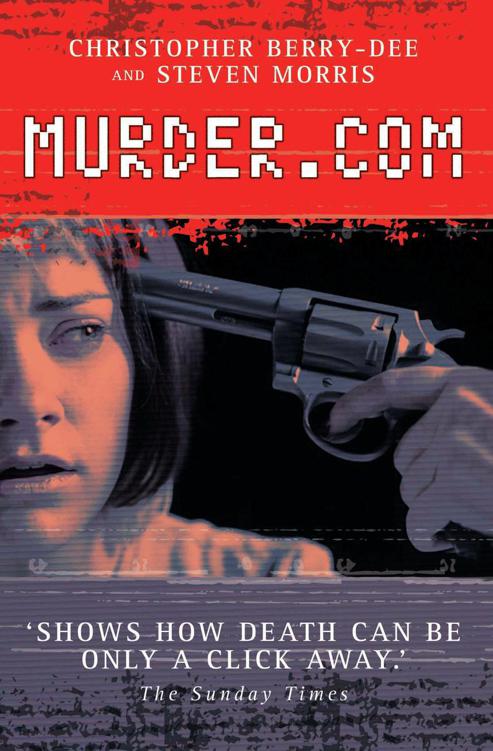

Murder.com

Authors: Christopher Berry-Dee,Steven Morris

In memoriam Jane Longhurst

In the Beginning There Was … Jeff Peters and Andy Takers

Armin Meiwes: Internet Cannibal

Jane Longhurst: Victim of a Necrophiliac

Suzy Gonzales: Internet Suicide

Anastasia Solovyova: In Search of a Dream

John E Robinson: Bodies in Barrels

Darlie Lynn Routier: The Dog that Didn’t Bark

Nancy Kissel: ‘The Milkshake Killer’

Susan Gray and ‘The Featherman’

Dr Robert

Johnson

: Missing, Presumed Dead!

Mona Jaud Awana: Cyber Terrorist

Satomi Mitarai: Surfed to Destruction

‘The attraction of the internet to so many people is you can be whoever or whatever you want to be. If you want to be Walter Mitty, you can be Walter Mitty. If you want to be out of the mainstream sexually, you can find company on the internet.’

P

AUL

J

ONES

, I

NSTITUTE FOR

A

DVANCED

T

ECHNOLOGY IN THE

H

UMANITIES,

U

NIVERSITY OF

V

IRGINIA

C

yberspace is a strange place, full of both happy and spine-chilling surprises. And there were certainly some of the second for luckless 28-year-old Trevor Tasker. This Englishman, from North Yorkshire, has understandably given up using the internet since discovering his new love was a 65-year-old pensioner with a corpse in her freezer.

After meeting her in a chatroom, the excited Trevor flew to South Carolina to meet Wynema Faye Shumate, who had posed as a sexy 30-something on the web. After hooking him with sexy chat, she had reeled him in with a semi-nude photo. Unbeknownst to her suitor, however, the shot had been taken some 30 years earlier.

Trevor’s shock on first setting eyes on his prospective lover turned to abject horror when he discovered that Wynema had put her dead housemate in the freezer. She had kept Jim O’Neil, who had died of natural causes, in cold storage for a year while she lived in his house and spent his money.

Sweet Wynema had also lopped off one of Jim’s legs with an axe because, somewhat inconveniently, he was too big to fit into the freezer. For the record, Shumate pleaded guilty to fraud and the unlawful removal of a dead body, and was given a year in prison.

Back home with his mum afterwards, Trevor told the

Daily Mirror

newspaper, ‘I’ll never log on again. When I saw her picture, I thought, “Wow”, but when she met me at the airport I almost had a heart attack. I certainly won’t go near internet chatrooms again.’

Well done, Trevor!

But there is a more serious side to our Introduction.

On 9 March 2004, a chilly Tuesday, the BBC reported that Britain and the USA were setting up a group to investigate ways of closing down internet sites depicting violent sex.

‘Initial steps have now been agreed by the Home Secretary David Blunkett and US Deputy Attorney General Jim Comey, during a meeting at the US Department of Justice in Washington DC,’ claimed the feature, adding, ‘The Jane Longhurst murder

case had horrified American officials because websites, featuring extreme sexual acts, were implicated in the trial of Englishman Graham Coutts, who had murdered the Brighton teacher.’

The sexual deviant Coutts trawled the web – there are more than 80,000 sites dedicated to ‘snuff’ and other killings, cannibalism, necrophilia and rape – then carried out his horrendous fantasy in real life by murdering Jane. The internet-inspired monster kept his victim’s body in a garden shed for 11 days, before moving her to a storage facility, where he committed necrophiliac acts on the corpse.

A senior detective from the National Criminal Intelligence Service (NCIS) told Christopher Berry-Dee, who visited New Scotland Yard in 2003, ‘In a short period of time, the internet has become the most exploited instrument of perversion known to man. It is like pumping raw sewage into people’s homes.’

Also very much to the point is the view of Ron P Hawley, Head of the North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation division which probes computer crimes: ‘It used to be you were limited by geography and transportation. The internet broadens the potential for contact. It’s another place to hang out for people predisposed to commit a crime.’

In addition to the countless millions of others hooked up to the web, more than a million people now use wireless technology (Wi-Fi) to access it, and a survey found that more than a third of Wi-Fi networks in London and Frankfurt lacked even basic security measures. It’s not surprising police throughout the world are increasingly concerned about Wi-Fi cyber crime – particularly the theft of bank details from computers. And some criminals, including paedophiles, are known to leave their networks unprotected so that they can

pretend that any illegal activities were not committed by them, attributing the offences instead to ‘piggybackers’, who log on to the internet via other users’ wireless connections.

Another assessment of the internet’s potential for crime comes from Yvonne Jukes, of the University of Hull, who claims, with perhaps a little overstatement, ‘Cyberspace opens up infinitely new possibilities to the deviant imagination. With access to the internet and sufficient know-how you can, if you are so inclined, buy a bride, cruise gay bars, go on a global shopping spree with someone else’s credit card, break into a bank’s security system, plan a demonstration in another country and hack into the Pentagon, all on the same day.’

Used with caution, the internet can be an educational and fun place. In fact, most of us have become so reliant on it that we could not conceive of a world without it. At the same time, we’re aware of the havoc that can be wrought by viruses on e-commerce when criminals or other hackers attempt to sabotage the web. Indeed, a particularly virulent virus – and more sophisticated forms are being developed all the time – could cause a catastrophe costing billions of dollars – one at least as economically devastating as the 9/11 attack on New York’s Twin Towers or Hurricane Katrina’s ravaging of New Orleans.

Most people seem to agree that, on balance, the worldwide web has improved our lives. However, among its defenders are those who claim that the advent of the internet, and even the ever-growing availability of virtual pornography, has in no way increased the overall crime figures; least of all that the medium has sparked an escalation in fraud, sexual and violent crime, or murder.

This book sets out to show that these commentators, well

meaning though they may be, could not be more misguided. For the shocking truth is that at no time in human history has crime rocketed to such epidemic proportions over such a short period. A major element in this rise is internet-related crime, which is increasing exponentially, and we can thank thousands of the webmasters hosting sites and search engines for helping things along the way.

To ignore this simple truth is to deny it. Some of us bury our heads in the sand, citing freedom of speech or civil liberties, wishing to demonstrate political correctness or simply concluding, ‘Ah well, the web is too powerful now to tackle the problem.’ But, if we follow this line of thinking, we will all soon live in a world where anything can happen to us and those appointed to defend our freedoms can do little, if anything, about it.

This brings me back to the well-meaning plans of David Blunkett (the former Home Secretary has since 2004 been succeeded by Charles Clarke) and the US Deputy Attorney General to shut down violent pornography sites. The reality is that, despite a massive UK–US crackdown in recent years, internet child pornography, much of it appallingly violent and degrading, has become a global epidemic of monstrous proportions. In Japan, for instance, Justice Minister Mayami Moryana has said, ‘The internet is fuelling a steady increase in child prostitution and pornography. It is a multi-million-dollar child sex trade.’

But this is just one disturbing issue, for US law-enforcement agencies are buckling under the pressure of investigating and bringing to justice

all types

of internet crime-related offences. Funding for police is not finite, nor is manpower. The policing system is creaking, even falling apart, because a large part of

these valuable resources is now being diverted to combat well-organised internet crime and lesser offences sparked off by the easy access to the web for the criminally inclined.

Right across Europe and in many parts of Asia, we find a mirror of America’s law-enforcement problems, with most countries now admitting almost total defeat in their efforts to curb internet-related crime or closing down sites displaying illegal material. The constant problem is that, as soon as a site is shut down, it reopens under a different domain name. As soon as a problem is located and stopped in one place, it re-emerges somewhere else – often in a more virulent strain – and the perpetrators do not even have to leave their desks to achieve it. In the absence of border controls – cyberspace is by its nature very difficult to police internationally – web-based criminality has become a cyber pandemic.

This is the dilemma now faced by the UK, the USA and other nations; a difficulty compounded in many countries by different interpretations and applications of civil and criminal law and, in the USA, by jurisdictional complications in law enforcement and by civil liberty laws that differ from state to state.

Yet there have been remarkable successes by the multinational task forces set up to catch both those who set up and those who visit child sex sites, and these are down to following the money trails, nearly always through identifying credit-card transactions. But any legislation agreed between the USA and the UK can only apply to sites set up in these countries. And even this is set to be further undermined in the UK as it is due to cede to Brussels much of its own ability to make law and dispense justice, rendering Anglo-American plans to get tough on internet crime all but meaningless.

One major area of crime where the internet’s rapid spread has become a highly effective tool is the people-trafficking industry. According to Channel Four’s docu-drama

Sex Traffic,

over 50,000 women a year are sold into the USA sex-trafficking trade, and most of the complex logistics are handled using the internet. Trafficking as a whole is growing to such an extent that experts estimate that anywhere from 700,000 to four million persons are now being traded annually throughout the world.

The ‘Brides for Sale’ business and similar internet scams cost Western males in excess of £4 million a year, and on the subject of this trade George M Nutwell III, Regional Security Officer in the US State Department at the US Embassy in Kiev, has written to the authors, ‘Ukraine has recently experienced a burgeoning crop of escort services and “marriage brokers” plying their trade on the internet. Your readers are cautioned against falling into the new Ukrainian “Love Trap”.’

A single scam against an Englishman netted a Russian internet dating agency around $11,000 – the staggering, if not obscene equivalent of 25 years’ wages for the average Russian citizen. By Western standards, this would be about $500,000. However, the flip side of the coin must not be ignored, for there are hundreds of web pages of advice on how to sensibly approach the task of finding a foreign bride on the internet. Many authorities say that if those seeking a wife are so dumb that they cannot find this advice, or choose to ignore it, they deserve all they get.

To widen the perspective, we now have cyber fraud, theft and just about every other criminal activity, including globally organised terrorism, being promoted and even carried out with the help of the internet. There are some 10,000 websites dedicated to cannibalism and necrophilia. In stomach-turning

detail, this book reveals how just one user of such material, Armin Meiwes, made his chilling fantasy come true.

Among the other ‘killers on the web’ you will meet in these pages is Sol Dos Reis, who is serving a lengthy prison term in the USA for the murder of a young girl he had met after grooming her on the web. Even today he still uses the internet in jail to lure young girls.

All varieties of sex were for sale 24 hours a day in Sharon Lopatka’s cyber world. She could provide almost anything anybody desired at any time. The police found it hard to believe that she could willingly board a train with her own murder as her destination. But Sharon wanted to die, and after she met her killer on the internet her wish was granted.

Anastasia Solovyova was a beautiful young woman who travelled from Russia to America to start a happy married life with a man she met on the internet. In a crime that sent shockwaves around the world, she ended up being horrifically abused and brutally murdered.

The sick and twisted John E Robinson became the world’s first cyber serial killer, graduating from the personal columns to the internet in search of prey. ‘Slavemaster’, as he styled himself on the net, kept his victims’ bodies in barrels on his remote American smallholding. He has recently been sentenced to death.

Nancy Kissel trawled the internet to seek out information about drugs that she could use to render her husband unconscious before she battered him to death. For his part, it appears, from testimony given by forensic computer experts at his wife’s trial in Hong Kong, that Robert Kissel was using the web to search for gay sex.

Susan Gray met an American cyber predator who ran amok in

Britain. He is still at large in the chatrooms and he could be targeting

you

, right now!

The internet also enabled Mona Jaud Awana, a hardline student with links to an Arab terrorist group, to lure a Jewish teenager to his death in Israel. And in an appalling incident in Japan – all the more horrific because it was committed by an 11-year-old child aggrieved by a perceived slight posted on the web – Satomi Mitarai was brutally murdered by her crazed, net-surfing school friend.

Did a knife-wielding maniac attack Darlie Routier in the dead of night? Or had someone else constructed a devilishly intricate plan? It was a crime that shocked America. Now she uses the internet from prison to raise thousands of dollars using deception to further her phoney claims of innocence. In a devastating re-examination of the case, the authors expose a Black Widow of the web.

In fact, hundreds of American male and female prisoners, a few of them serial killers, use the internet to rip off thousands of dollars from gullible sympathisers. Some of the girls post photos of supermodels on the web as a come-on, while others use internet agencies to find pen friends.

It was bound to happen. First, proponents of the culture of death brought us physician-assisted suicide (PAS). Now we must contend with internet-assisted suicide (IAS).