My Amputations (Fiction collective ;)

Read My Amputations (Fiction collective ;) Online

Authors: Clarence Major

Books by Clarence Major

My Amputations

Emergency Exit

Reflex and Bone Structure

NO

All-Night Visitors

Inside Diameter: The France Poems

The Syncopated Cakewalk

The Cotton Club

Symptoms and Madness

Private Line

Swallow the Lake

The Dark and Feeling

Dictionary of Afro-American Slang

The New Black Poetry

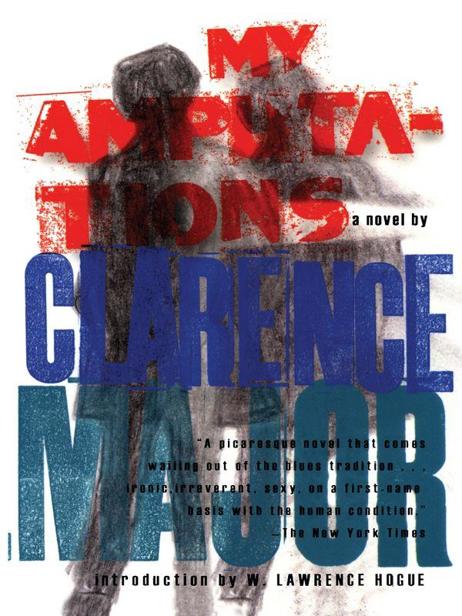

MY AMPUTATIONS

a novel by

CLARENCE MAJOR

with an introduction by

W. Lawrence Hogue

The University of Alabama Press

Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35487-0380

Copyright © 1986 Clarence Major

Introduction copyright © 2008 The University of Alabama Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Published by FC2, and imprint of the University of Alabama Press, with support provided by Florida State University and the Publications Unit of the Department of English at Illinois State University

Address all editorial inquiries to: Fiction Collective Two, Florida State University, c/o English Department, Tallahassee, FL 32306-1580

∞

The paper on which this book is printed meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Science–Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data available from the Library of Congress.

Author's note: The characters in this novel are products of my own imagination and are not in any way based on actual persons or actual experiences. Any resemblance to actual persons anywhere is coincidental.

ISBN-13: 978-1-57366-838-5 (electronic)

To the people who must find themselves

“You are you because your little

dog knows you.” —Gertrude Stein

W. Lawrence Hogue

When

My Amputations

was published in 1986, it was heralded by writers and critics as a major literary achievement. Toni Morrison, Ntozake Shange, and Charles Johnson spoke of Clarence Major's mind and talent, his inventive use of language that drew together influences from black music, poetry, the blues, and painting. A reviewer for the

New York Times

wrote that

My Amputations

is “distinguished by a rich and imaginative prose poetry of evocative power.” Awarding it the 1986 Western States Book Award for Fiction, jurors Denise Levertov, Robert Haas, Jonathan Galassi, and Sandra Cisneros deemed the text “an explosively rich book about a man pursued by his shadow. . . .

My Amputations

is distinguished by the extraordinarily inventive rhythms of its language. A book full of laughter and rueful sadness and swift contempt, its deepest resonance is the hunger to be healed.” The critic Jerome Klinkowitz wrote that

My Amputations

is “living fiction, as close to a truly organic text as we are ever likely to see.”

Since this extraordinary reception, the study of contemporary literature has evolved dramatically, providing contemporary critics and scholars with the language, vocabulary, and theoretical concepts to re-read

My Amputations

, not as an “experimental” text, but as a masterpiece of postmodern fiction, as a catalyst in a new historical and epistemological development in American literature. Reflexivity, fragmented authority, indeterminacy, play, uncertainty, difference, ambiguity, and open-endedness—these post-structural and postmodern concepts challenge many of the suppositions of modern thought and modern literature. As a consequence, traditional notions of realism seem inadequate. The proposition that the writer is the “creator” of something “original” has

come under serious attack. The unquestioned assumption of the text's literariness—that is, that the text possesses certain qualities that place it above the matrices of historical conditions—has been undermined profoundly. By questioning so many naturalized conventions and assumptions about modern literature,

My Amputations

signifies new ways to think and live in the world. Most importantly, these advancements and developments allow critics to point out how this text radically re-describes African American subjectivity.

In the 1970s and 1980s, as academics and critics struggled to come up with new uses for literature, Clarence Major had already embarked upon a literary mission to re-define the novel. Indeed, so many of the postmodern tendencies highlighted by literary theorists, and so abundantly present in

My Amputations

, had been evident in Major's work for years prior to that. In an interview early in his writing career, Major told John O'Brien: “the novel . . . takes on its own reality and is really independent of anything outside itself. . . . You begin with words and you end with words. The content exists in our minds. I don't think that it has to be a reflection of anything. It is a reality that has been created inside a book. It's put together and exists finally in your mind.”

1

For Major, from

All-Night Visitors

(1969) to

No

(1973) to

Reflex and Bone Structure

(1975), to

Emergency Exit

(1979) and to

My Amputations

(1986), these texts do not reflect the social real; they are an addition to it, or are artistic objects in themselves to be admired for what they are. They have their own presence in the world, representing complex networks of ideas, images, and feeling. They refer only to themselves and to other texts. In the earlier novels

All-Night Visitors

and

No

, Major uses graphic sex to demonstrate that fiction is a linguistic invention. In later novels such as

Reflex and Bone Structure, Emergency Exit

, and

My Amputations

, Major uses personal fragmentation to

explore anti-realism or the fiction-making process.

From the beginning, this knowledge and awareness gave Major the freedom to use his imagination to create fiction that allows the reader to have an experience, rather than an ill-conceived reflection of life. Choosing not to model his fiction on “the linear and formal notion of realism traditionally practiced by Negro and Black American writers,”

2

Major eschews linear plot, causal logic, progress, realistic character development, and resolution. He expands the novel to incorporate other forms of speech and images such as painting, jazz and blues improvisation, techniques of detective fiction, porn movies, and cubism, as he speaks to human dimensions and possibilities that have been repressed and/or excluded in realistic texts. But in using these different forms of representation, he disturbs and even subverts their dominance, causing them to exist in this inter-textual flux.

In the 1970s, this must have been an arduous, difficult task for Major. He began writing his postmodern, anti-establishment fiction and achieving literary recognition in the aftermath of the turmoil of the 1960s. This was a time when individuals and artistic and literary communities drew clearly defined cultural and ideological lines. In many ways, he was marginalized. In not writing realistic fiction or catering to the New York literary establishment, he did not achieve the commercial successes of his contemporaries such as Alice Walker and Toni Morrison. Also, in the 1970s and 1980s, Major's brand of meta-fiction put him in direct opposition to black aesthetics and the racial uplift of African American critics, as well as in opposition to mainstream American literary critics who read African American literature in a reductive, stereotypical way. He readily responded, arguing that a black aesthetic view of literature was as stifling and repressive as a Eurocentric view. Both close down the writer and restrict him to the service of certain political ideologies.

He was also accused of not writing about “real” black people, or dealing with race.

But Major does deal with race. Rather than choose race as his theme and racial conflict as his subject matter, Major probes beyond the merely political to find the roots that link the African American experience to all human experiences. His characters are black, but race “is not the totality of their identity.”

3

For Major, blacks have other human identities and dimensions. In taking this approach to African American subjectivity, he obviates the “tendency to stereotype the [black] Other”

4

and instead represents blacks as complex and varied, with the experience of race being one aspect of that complex existence.

Major's

My Amputations

is told by an omniscient narrator who shifts from third person to first person, moving in and out of the mind of the protagonist, Mason. The text has many modes: impressionistic, visual, and meta-fictional. Minimizing representational effects, it constructs the narrative in physical blocks of diverse materials, rather than in logical paragraphs. One of its techniques includes using language to build what Major calls “visual panels,”

5

like Cubist pictures, which are complete within themselves. But within each block, which is filled with multiple and varied poetic imagery, the narrator constantly moves forward and backward in time.

Another technique used in

My Amputations

is a jazz/blues mode of improvisation that offers different takes on key situations and events. When the narrator tells the story of Mason Ellis in a jazz/blues style, he repeats information always with variations. For example, the narrator tells us of Mason's childhood in Chicago. But when he recounts Mason's childhood a second time, he also tells us that Mason was born in red-dirt Georgia. In his jazz-influenced account of Painted Turtle, one of Mason's female friends, the narrator tells us of her relationship with Mason and how it ends. Later, he does a riff on

the relationship, but this time he elaborates further, recounting how the two first met.

This riffing on various themes and situations happens throughout the text. The narrator gives us several different versions of Mason's stay in the Air Force. He gives different riffs on the Chemical Bank robbery, without hierarchy or privilege. In giving us this play on the various events and situations in the text, the narrator, and thus Major, demonstrates that language cannot completely master a subject, that language cannot pin down meaning. It can only give us significations of the subject or the social real.

But as the narrator gives us the story of Mason Ellis in these blocked, discontinuous, jazz-styled modes, he interrupts the narrative and comments on the processes of producing the text. Very early in

My Amputations

, the narrator presents a block filled with diverse images of his childhood: his days in the Air Force, his desire to write, and the presence of his muse Celt, with allusions to Toomer, Conrad, Zola, Dickens, and others. Halfway through the block he asks, “Realism? Not really” (10). In another imagined block about robbing Chemical Bank, the narrator disrupts the narrative and asks, “If I tie a string to his nervous little finger and connect it to a large C hanging, say, in the sky, then connect the C to Celt and from her stretch it from myself to Mason, then jerk the end of the damn-thing—what would happen? Would I get any added up, totalized meaning, plot?” (37) The questions are a play on traditional fiction's desire to arrive, through causal progression, at a resolution. Of course, Major raises these questions in a text that does neither. Later, the narrator rejects “the assumption that language offered a logical means by which one might understand” (54), undermining the naturalized notion that fiction tells the “truth,” that fiction is a “model for reality” (54). Lastly, in his lecture at

Sarah Lawrence, Mason tells members of his audience that they should think of him as a character in a novel, revealing himself as a fictional construct. In exposing the writing process, Major demonstrates that

My Amputations

is necessarily bound to social reality only by its status as an artifact within that world and by virtue of it being an extension of an author whose imaginative acts brought it into existence.

Finally, Major plays with the idea of authorship in

My Amputations

, echoing the postmodern idea of the death of the author. In an interview, Major states: “Exploring different personae in my earlier novels was something that grew out of my sense of personal fragmentation. . . . Back when I was starting out to write, it felt perfectly natural to have my work reflect this sense that I was literally a different person every time I sat down to write. It was an interesting challenge to find narrative contexts for different parts of myself that needed voices to express themselves.”

6

In a Lacanian sense, Major is defining subjectivity, including his own, as relative, multiple, de-centered, contradictory, and shifting. According to Jacques Lacan, the “real,” which is excluded from representation, resists “symbolization absolutely.”

7

Therefore, the subject we get in language is not whole; it is fractured and distorted. This distortion is manifested as lack of being, and it is this void that desire constantly attempts to fill. Thus, the “I” becomes a network of signifiers that exists in and embodies language. Because the Lacanian self/I has several selves/signifiers, it becomes difficult to gain access to the self through language, especially since language continually misrepresents the self as being whole.

This is the problem of the writer when he makes himself his subject. By introducing the Author who has assumed the name of Clarence McKay (with initials C. M., the same as Clarence Major, who becomes the Imposter) into the text, Major creates a fictional self within the narrative. But the narrator—who

sometimes refers to himself as “me”—and Mason are also selves or “different parts” of the Author, Clarence Major. The narrator, who is hip, ironic, versed in jazz and blues, and knows literature, art, and classical music, sounds very much like Clarence Major. Mason, like Major, does a stint in the Air Force. Also like Major, he is the author of two novels and an anthology of Afro-American slang. In focusing on the meta-fictional aspects of literature, he, like Major, thinks that imagination and pushing the boundaries of language are important dimensions of fiction. If C. M., Mason, and the narrator are linguistic constructs of Clarence Major, they serve as an ironic frame for Clarence Major's own logocentric quest for origin and mastery, a quest he continually deconstructs.

In the midst of this awareness of language, narrative, and subjectivity,

My Amputations

, in a fragmented and discontinuous form, gives us provisionally the story of Mason Ellis, who is born in Georgia but is raised in Chicago. After his father leaves, his mother remarries and he lives with his mother, stepfather, and two sisters. He wants to write, and he possesses a muse who guides him. At eighteen, he enters the Air Force, where he spends time in Cheyenne, Wyoming; San Antonio, Texas; Valdosta, Georgia; and Florida, experiencing humiliating racism before being honorably discharged and returning to Chicago. His first marriage to Judith results in six children in the “wink of a birthcontrolless eye” (12), but he has difficulties providing for them. When a caseworker tells him that the father's absence will mean larger paychecks for his family, he leaves. Six months after he meets Mary Lou, she gives birth to triplets, and his dream of becoming a famous writer vanishes, until he steals C. M.'s identity.

Mason also has a criminal dimension to his existence, a history of petty theft. While in New York, he is arrested, and he serves time in Attica, where he becomes a reader. In

fact, in Attica he reads the Author's works repeatedly until he convinces himself that he is the Author. One day while he is watching an award ceremony on television, he witnesses the Author accept an award and money. He believes that the Author has stolen his identity. When he is paroled from prison, Mason breaks into the Author's apartment, beats him up, and demands money. Mason kidnaps the Author and subjects him to torture, but the Author refuses to break, forcing Mason to put him on a freight train bound for the West. After successfully assuming the Author's identity, Mason barges into the office of the publisher, Ferrand, and demands money. Later, he seals his identity by getting a fake passport that “proves” he is the Author. Now that he has become the Author, with one of the sheets in his pocket identifying him as “post-modern” (53), he must figure out what the term means. More importantly, he has to answer the question, “Who am I, really?”