My Childhood (11 page)

I knew that I must not run after grandmother at such a time, and I was afraid to be alone, so I went down to grandfather's room; but directly he saw me, he cried:

"Get out! Curse you!"

I ran up to the garret and looked out on the yard and garden from the dormer-window, trying to keep grandmother in sight. I was afraid that they would kill her, and I screamed, and called out to her, but she did not come to me; only my drunken uncle, hearing my voice, abused my mother in furious and obscene language.

On one of these evenings grandfather was unwell, and as he uneasily moved his head, which was swathed in a towel, upon his pillow, he lamented shrilly:

"For this I have lived, and sinned, and heaped up riches! If it were not for the shame and disgrace of it, I would call in the police, and let them be taken before the Governor to-morrow. But look at the disgrace! What sort of parents are they who bring the law to bear on their children? Well, there 's nothing for you to do but to lie still under it, old man!"

He suddenly jumped out of bed, and went, staggeringly, to the window.

Grandmother caught his arm: "Where are you going?" she asked.

"Light up!" he said, breathing hard.

When grandmother had lit the candle, he took the candlestick from her, and holding it close to him, as a soldier would hold a gun, he shouted from the window in loud, mocking tones:

"Hi, Mischka! You burglar! You mangy, mad

Instantly the top pane of glass was shattered to atoms, and half a brick fell on the table beside grandmother.

"Why don't you aim straight?" shrieked grandfather hysterically.

Grandmother just took him in her arms, as she would have taken me, and carried him back to bed, saying over and over again in a tone of terror:

"What are you thinking of? What are you thinking of? May God forgive you! I can see that Siberia will be the end of this for him. But in his madness he can't realize what Siberia would mean."

Grandfather moved his legs angrily, and sobbing dryly, said in a choked voice:

"Let him kill me--!"

From outside came howls, and the sound of trampling feet, and a scraping at walls. I snatched the brick from the table and ran to the window with it, but grandmother seized me in time, and hurling it into a corner, hissed:

"You little devil!"

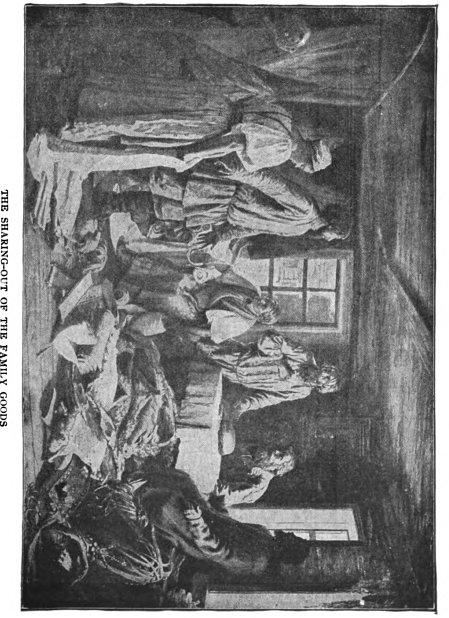

Another time my uncle came armed with a thick stake, and broke into the vestibule of the house from the yard by breaking in the door as he stood on the top of the dark flight of steps. However, grandfather was waiting for him on the other side, stick in hand, with two of his tenants armed with clubs, and the tall wife of the innkeeper holding a rolling-pin in readiness. Grandmother came softly behind them, murmuring in tones of earnest entreaty:

"Let me go to him! Let me have one word with him!"

Grandfather was standing with one foot thrust forward like the man with the spear in the picture called "The Bear Hunt." When grandmother ran to him, he said nothing, but pushed her away by a movement of his elbow and his foot. All four were standing in formidable readiness. Hanging on the wall above them was a lantern which cast an unflattering, spasmodic light on their countenances. I saw all this from the top staircase, and I was wishing all the time that I could fetch grandmother to be with me up there.

My uncle had carried out the operation of breaking in the door with vigor and success. It had slipped out of its place and was ready to spring out of the upper hinge--the lower one was already broken away and jangled discordantly.

Grandfather spoke to his companions-in-arms in a voice which repeated the same jarring sound:

"Go for his arms and legs, but let his silly head alone, please."

In the wall, at the side of the door, there was a little window, through which you could just put your head. Uncle had smashed the panes, and it looked, with the splinters sticking out all round it, like some one's black eye. To this window grandmother rushed, and putting her hand through into the yard, waved it warningly as she cried:

"Mischka! For Christ's sake go away; they will tear you limb from limb. Do go away!"

He struck at her with the stake he was holding. A broad object could be seen distinctly to pass the window and fall upon her hand, and following on this grandmother herself fell; but even as she lay on her back she managed to call out:

"Mischka! Mi--i--schka! Run!"

"Mother, where are you?" bawled grandfather in a terrific voice.

The door gave way, and framed in the black lintel stood my uncle; but a moment later he had been hurled, like a lump of mud off a spade, down the steps.

The wife of the innkeeper carried grandmother to grandfather's room, to which he soon followed her, asking morosely:

"Any bones broken?"

"Och! I should think every one of them was broken," replied grandmother, keeping her eyes closed. "What have you done with him? What have you done with him?"

"Have some sense!" exclaimed grandfather sternly. "Do you think I am a wild beast? He is lying in the cellar bound hand and foot, and I 've given him a good drenching with water. I admit it was a bad thing to do; but who caused the whole trouble?"

Grandmother groaned.

"I have sent for the bone-setter. Try and bear it till he comes," said grandfather, sitting beside her on the bed. "They are ruining us, Mother--and in the shortest time possible."

"Give them what they ask for then."

"What about Varvara?"

They discussed the matter for a long time--grandmother quietly and pitifully, and grandfather in loud and angry tones.

Then a little, humpbacked old woman came, with an enormous mouth, extending from ear to ear; her lower jaw trembled, her mouth hung open like the mouth of a fish, and a pointed nose peeped over her upper lip. Her eyes were not visible. She hardly moved her feet as her crutches scraped along the floor, and she carried in her hand a bundle which rattled.

It seemed to me that she had brought death to grandmother, and darting at her I yelled with all my force:

"Go away!"

Grandfather seized me, not too gently, and, looking very cross, carried me to the attic.

CHAPTER VI

WHEN the spring came my uncles separated-- Jaakov remained in the town and Michael established himself by the river, while grandfather bought a large, interesting house in Polevoi Street, with a tavern on the ground-floor, comfortable little rooms under the roof, and a garden running down to the causeway which simply bristled with leafless willow branches.

"Canes for you!" grandfather said, merrily winking at me, as after looking at the garden, I accompanied him on the soft, slushy road. "I shall begin teaching you to read and write soon, so they will come in handy."

The house was packed full of lodgers, with the exception of the top floor, where grandfather had a room for himself and for the reception of visitors, and the attic, in which grandmother and I had established ourselves. Its window gave on to the street, and one could see, by leaning over the sill, in the evenings and on holidays, drunken men crawling out of the tavern and staggering up the road, shouting and tumbling about. Sometimes they were thrown out into the road, just as if they had been sacks, and then they would try to make their way into the tavern again; the door would bang, and creak, and the hinges would squeak, and then a fight would begin. It was very interesting to look down on all this.

Every morning grandfather went to the workshops of his sons to help them to get settled, and every evening he would return tired, depressed, and cross.

Grandmother cooked, and sewed, and pottered about in the kitchen and flower gardens, revolving about something or other all day long, like a gigantic top set spinning by an invisible whip; taking snuff continually, and sneezing, and wiping her perspiring face as she said:

"Good luck to you, good old world! Well now, Oleysha, my darling, isn't this a nice quiet life now? This is thy doing, Queen of Heaven--that everything has turned out so well!"

But her idea of a quiet life was not mine. From morning till night the other occupants of the house ran in and out and up and down tumultuously, thus demonstrating their neighborliness--always in a hurry, yet always late; always complaining, and always ready to call out: "Akulina Ivanovna!"

And Akulina Ivanovna, invariably amiable, and impartially attentive to them all, would help herself to

snuff and carefully wipe her nose and fingers on a red check handkerchief before replying:

"To get rid of lice, my friend, you must wash yourself oftener and take baths of mint-vapor; but if the lice are under the skin, you should take a tablespoonful of the purest goose-grease, a teaspoonful of sulphur, three drops of quicksilver--stir all these ingredients together seven times with a potsherd in an earthenware vessel, and use the mixture as an ointment. But remember that if you stir it with a wooden or a bone spoon the mercury will be wasted, and that if you put a brass or silver spoon into it, it will do you harm to use it."

Sometimes, after consideration, she would say:

"You had better go to Asaph, the chemist at Petchyor, my good woman, for I am sure I don't know how to advise you."

She acted as midwife, and as peacemaker in family quarrels and disputes; she would cure infantile maladies, and recite the "Dream of Our Lady," so that the women might learn it by heart "for luck," and was always ready to give advice in matters of housekeeping.

"The cucumber itself will tell you when pickling time comes; when it falls to the ground and gives forth a curious odor, then is the time to pluck it. Kvass must be roughly dealt with, and it does not like much sweetness, so prepare it with raisins, to which you may

add one zolotnik to every two and a half gallons. . . . You can make curds in different ways. There 's the Donski flavor, and the Gimpanski, and the Caucasian."

All day long I hung about her in the garden and in the yard, and accompanied her to neighbors' houses, where she would sit for hours drinking tea and telling all sorts of stories. I had grown to be a part of her, as it were, and at this period of my life I do not remember anything so distinctly as that energetic old woman, who was never weary of doing good.

Sometimes my mother appeared on the scene from somewhere or other, for a short time. Lofty and severe, she looked upon us all with her cold gray eyes, which were like the winter sun, and soon vanished again, leaving us nothing to remember her by.

Once I asked grandmother: "Are you a witch?"

"Well! What idea will you get into your head next?" she laughed. But she added in a thoughtful tone: "How could I be a witch? Witchcraft is a difficult science. Why, I can't read and write even; I don't even know my alphabet. Grandfather--he 's a regular cormorant for learning, but Our Lady never made me a scholar."

Then she presented still another phase of her life to me as she went on:

"I was a little orphan like you, you know. My mother was just a poor peasant woman--and a cripple. She was little more than a child when a gentleman took advantage of her. In fear of what was to come, she threw herself out of the window one night, and broke her ribs and hurt her shoulder so much that her right hand, which she needed most, was withered . . . and a noted lace-worker, too! Well, of course her employers did not want her after that, and they dismissed her--to get her living as well as she could. How can one earn bread without hands? So she had to beg, to live on the charity of others; but in those times people were richer and kinder . . . the carpenters of Balakhana, as well as the lace-workers, were famous, and all the people were for show.

"Sometimes my mother and I stayed in the town for the autumn and winter, but as soon as the Archangel Gabriel waved his sword and drove away the winter, and clothed the earth with spring, we started on our travels again, going whither our eyes led us. To Mourome we went, and to Urievitz, and by the upper Volga, and by the quiet Oka. It was good to wander about the world in the spring and summer, when all the earth was smiling and the grass was like velvet; and the Holy Mother of God scattered flowers over the fields, and everything seemed to bring joy to one, and speak straight to one's heart. And sometimes, when we were on the hills, my mother, closing her blue eyes, would begin to sing in a voice which, though not powerful, was as clear as a bell; and listening to her, everything about us seemed to fall into a breathless sleep. Ah! God knows it was good to be alive in those days!

"But by the time that I was nine years old, my mother began to feel that she would be blamed if she took me about begging with her any longer; in fact, she began to be ashamed of the life we were leading, and so she settled at Balakhana, and went about the streets begging from house to house--taking up a position in the church porch on Sundays and holidays, while I stayed at home and learned to make lace. I was an apt pupil, because I was so anxious to help my mother; but sometimes I did not seem to get on at all, and then I used to cry. But in two years I had learned the business, mind you, small as I was, and the fame of of it went through the town. When people wanted really good lace, they came to us at once:

"'Now, Akulina, make your bobbins fly!'"

"And I was very happy . . . those were great days for me. But of course it was mother's work, not mine; for though she had only one hand and that one useless, it was she who taught me how to work. And a good teacher is worth more than ten workers.

"Well, I began to be proud. 'Now, my little mother,' I said, 'you must give up begging, for I can earn enough to keep us both.'

"'Nothing of the sort!' she replied. 'What you earn shall be set aside for your dowry.'

"And not long after this, grandfather came on the scene. A wonderful lad he was--only twenty-two, and already a freewater-man. His mother had had her eye on me for some time. She saw that I was a clever worker, and being only a beggar's daughter, I suppose she thought I should be easy to manage; but--! Well, she was a crafty, malignant woman, but we won't rake up all that. . . . Besides, why should we remember bad people? God sees them; He sees all they do; and the devils love them."

And she laughed heartily, wrinkling her nose comically, while her eyes, shining pensively, seemed to caress me, more eloquent even than her words.

I remember one quiet evening having tea with grandmother in grandfather's room. He was not well, and was sitting on his bed undressed, with a large towel wrapped round his shoulders, sweating profusely and breathing quickly and heavily. His green eyes were dim, his face puffed and livid; his small, pointed ears also were quite purple, and his hand shook pitifully as he stretched it out to take his cup of tea. His manner was gentle too; he was quite unlike himself.

"Why have n't you given me any sugar?" he asked pettishly, like a spoiled child.

"I have put honey in it; it is better for you," replied grandmother kindly but firmly.

Drawing in his breath and making a sound in his throat like the quacking of a duck, he swallowed the hot tea at a gulp.

"I shall die this time," he said; "see if I don't!"

"Don't you worry! I will take care of you."

"That's all very well; but if I die now I might as well have never lived. Everything will fall to pieces."

"Now, don't you talk. Lie quiet."

He lay silent for a minute with closed eyes, twisting his thin beard round his fingers, and smacking his discolored lips together; but suddenly he shook himself as if some one had run a pin into him, and began to utter his thoughts aloud:

"Jaaschka and Mischka ought to get married again as soon as possible. New ties would very likely give them a fresh hold on life. What do you think?" Then he began to search his memory for the names of eligible brides in the town.

But grandmother kept silence as she drank cup after cup of tea, and I sat at the window looking at the evening sky over the town as it grew redder and redder and cast a crimson reflection upon the windows of the opposite houses. As a punishment for some misdemeanor, grandfather had forbidden me to go out in the garden or the yard. Round the birch trees in the garden circled beetles, making a tinkling sound with their wings; a cooper was working in a neighboring yard, and not far away some one was sharpening knives. The voices of children who were hidden by the thick bushes rose up from the garden and the causeway. It all seemed to draw me and hold me, while the melancholy of eventide flowed into my heart.

Suddenly grandfather produced a brand-new book from somewhere, banged it loudly on the palm of his hand, and called me in brisk tones.

"Now, you young rascal, come here! Sit down! Now do you see these letters? This is'Az.' Say after me 'Az,' 'Buki,' 'Viedi.' What is this one?"

"Buki."

"Right! And what is this?"

"Viedi."

"Wrong! It is 'Az.*

"Look at these--'Glagol,' 'Dobro,' Test.' What is this one?"

"Dobro."

"Right! And this one?"

"Glagol."

"Good! And this one?"

"Az."

"You ought to be lying still, you know, Father," put in grandmother.

"Oh, don't bother! This is just the thing for me; it takes my thoughts off myself. Go on, Lexei!"

He put his hot, moist arm round my neck, and ticked off the letters on my shoulder with his fingers. He smelled strongly of vinegar, to which an odor of baked onion was added, and I felt nearly suffocated; but he flew into a rage and growled and roared in my ear:

"'Zemlya,' 'Loodi'!"

The words were familiar to me, but the Slav characters did not correspond with them. "Zemlya" (Z) looked like a worm; "Glagol" (G) like round-shouldered Gregory; "Ya" resembled grandmother and me standing together; and grandfather seemed to have something in common with all the letters of the alphabet.

He took me through it over and over again, sometimes asking me the names of the letters in order, sometimes "dodging"; and his hot temper must have been catching, for I also began to perspire, and to shout at the top of my voice--at which he was greatly amused. He clutched his chest as he coughed violently and tossed the book aside, wheezing:

"Do you hear how he bawls, Mother? What are you making that noise for, you little Astrakhan maniac? Eh?"

"It was you that made the noise."

It was a pleasure to me then to look at him and at grandmother, who, with her elbows on the table, and cheek resting on her hand, was watching us and laughing gently as she said:

"You will burst yourselves with laughing if you are not careful."

"I am irritable because I am unwell," grandfather explained in a friendly tone. "But what's the matter with you, eh?"

"Our poor Natalia was mistaken," he said to grandmother, shaking his damp head, "when she said he had no memory. He has a memory, thank God! It is like a horse's memory. Get on with it, snub-nose!"

At last he playfully pushed me off the bed.

"That will do. You can take the book, and tomorrow you will say the whole alphabet to me without a mistake, and I will give you five kopecks."

When I held out my hand for the book, he drew me to him and said gruffly:

"That mother of yours does not care what becomes of you, my lad."

Grandmother started.

"Oh, Father, why do you say such things?"

"I ought not to have said it--my feelings got the better of me. Oh, what a girl that is for going astray!"

He pushed me from him roughly.

"Run along now! You can go out, but not into the street; don't you dare to do that. Go to the yard or the garden."

The garden had special attractions for me. As soon as I showed myself on the hillock there, the boys in the causeway started to throw stones at me, and I returned the charge with a will.

"Here comes the ninny," they would yell as soon as they saw me, arming themselves hastily. "Let's skin him!"

As I did not know what they meant by "ninny," the nickname did not offend me; but I liked to feel that I was one alone fighting against the lot of them, especially when a well-aimed stone sent the enemy flying to shelter amongst the bushes. We engaged in these battles without malice, and they generally ended without any one being hurt.

I learned to read and write easily. Grandmother bestowed more and more attention on me, and whippings became rarer and rarer--although in my opinion I deserved them more than ever before, for the older and more vigorous I grew the more often I broke grandfather's rules, and disobeyed his commands; yet he did no more than scold me, or shake his fist at me. I began to think, if you please, that he must have beaten me without cause in the past, and I told him so.

He lightly tilted my chin and raised my face towards him, blinking as he drawled:

"Wha--a--a--t?"

And half-laughing, he added:

"You heretic! How can you possibly know how many whippings you need? Who should know if not I? There! get along with you."

But he had no sooner said this than he caught me by the shoulder and asked:

"Which are you now, I wonder--crafty or simple?"

"I don't know."

"You don't know! Well, I will tell you this much--be crafty; it pays! Simple-mindedness is nothing but foolishness. Sheep are simple-minded, remember that! That will do. Run away!"

Before long I was able to spell out the Psalms. Our usual time for this was after the evening tea, when I had to read one Psalm.

"B-l-e-s-s, Bless; e-d, ed; Blessed," I read, guiding the pointer across the page. "Blessed is the man-- Does that mean Uncle Jaakov?" I asked, to relieve the tedium.