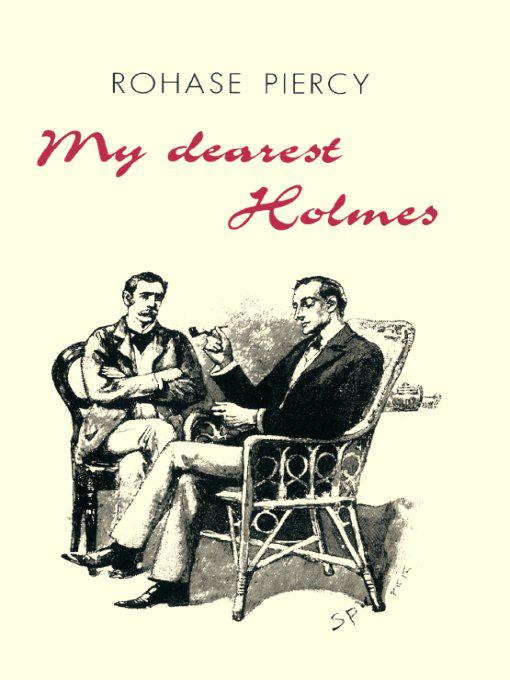

My Dearest Holmes

Authors: Rohase Piercy

Copyright (c) 2007 Rohase Piercy

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 1-4196-7632-6

ISBN-13: 978-1419676321

E-Book ISBN: 978-1-61550-907-2

Visit

www.booksurge.com

to order additional copies.

The following instructions were found attached to the present manuscript; which, along with other accounts of a similar nature, have passed into my hands from a source which I am not at present at liberty to disclose.

Since they bear directly upon the circumstances under which Dr Watson wrote this account, I have reproduced them here, by way of a preface.

Rohase Piercy

It is my specific wish and intention that the manuscripts contained in this box be left unopened, unread and unpublished until one hundred years have passed since the events described in the first account (namely the year 1887).

If this length of time appears in retrospect to have been excessive, I can only apologise to the future generation. It seems to me now, in this first decade of the new century, that some further decades at least must elapse before these reminiscences can be received with such sympathy and respect as I hope will one day be possible.

The accounts of these cases have never passed through the hands of my literary agent, Dr Conan Doyle, nor do I intend that they ever shall; they are too bound up with events in my personal life which, although they may provide a plausible commentary to much of what must otherwise seem implausible in my published accounts of my dealings with Mr Sherlock Holmes, can never be made public while he or I remain alive. However, it is my hope that, when all those involved have long passed beyond all censure, these accounts may see the light of a happier day than was ever, alas, granted to us.

John H. Watson, M.D

London 1907

Contents

--

I

--

I

HAVE OFTEN been accused of being imprecise in my datings of the many of his cases in which my friend, Mr Sherlock Holmes, allowed me to play a part; in reply I usually allude to the delicacy with which the subject matter of many of the said cases demands that they be treated.

How much more so does this apply to the present narrative!

However, it has always been possible for the discerning reader to make an accurate placing of a particular case, and since it is questionable whether this story will ever see the light of day, I see still less reason to be overly cautious; much will be explained, then, by my simply stating that the events I am about to describe took place during the January before the Sholto affair, which I have presented for public consumption under the title of 'The Sign of Four'.

Mr Sherlock Holmes had spent several days in bed, as was his habit from time to time. He was indulging in one of those periods of lassitude which frequently overtook him between cases. On this occasion, he had gone so far as to confine himself to his room, whither he had conveyed his old clay pipe, the Persian slipper containing his shag tobacco, and his cocaine bottle and hypodermic syringe; presumably he wished to avoid altogether my expressions of concern and censure on the subject of self-poisoning. I was left to console myself with the contents of the spirit flask, and to make some half-hearted attempt to restore order to the chaos of our sitting room, now that I at last had the opportunity.

I had no enthusiasm for the task, however. The melancholy which had crept up on me over the last few months seemed set to stay with me, and Holmes' withdrawal of his society served to throw my unhappy situation into even sharper relief. Forlornly I contemplated the relics of our six years' shared tenancy of the said sitting room; so much of him, it seemed, and so little of me. His books and newspapers lay in drifts in every corner. The spattered table on which his chemicals and test-tubes stood neglected would, I was sure, express feelings very similar to mine, if some miracle were to render it animate; the reference books and commonplace books on his shelf beside the fireplace, cross-indexed and kept meticulously up to date, evinced more signs of loving care than either of us; and when I found myself expressing a morbid sympathy with the sheets of unanswered correspondence firmly skewered to the mantelpiece by the wretched man's jack-knife, I decided that it was high time to abandon the whole idea of wasting any loving care on 221 B Baker Street, and to seek solace elsewhere. Consequently, I absented myself from our lodgings, and spent most of my time in the environs of Piccadilly, returning in the early hours of the morning, somewhat the worse for wine.

Thus it was that I was not present when the first interview took place between Miss Anne D'Arcy and Mr Sherlock Holmes. It was over by the time I arrived back at Baker Street. I made my way unsteadily to my room, and flinging my clothes upon the floor and myself upon the bed with very little ceremony, was insensible in a matter of seconds. Due to the excessive amount of alcohol in my blood, I must have passed out rather than slept for the first few hours; and it seemed to me that it was still the middle of the night when I was dragged unwillingly into wakefulness by a tugging at my shoulder.

'Watson. Wake up.'

I gave a violent start, my eyes sprung open to the cold sunlight of a January morning. Sherlock Holmes was standing by my bed in his mouse-coloured dressing gown, his unsavoury before-breakfast pipe in his mouth. Amusement played about his lips as he surveyed me from under heavy lids, his head on one side.

'It is nine o'clock, Watson,' he said as I blinked stupidly up at him, propped upon one elbow in the bed. 'Breakfast is laid downstairs.'

It took me some time to gather my wits. I had hardly set eyes on him for days on end, much less been able to persuade him to eat with me at the proper times, and here he was, not only out of bed and ready for breakfast, but apparently anxious that I should share it with him.

'What's got into you, Holmes?' I demanded, adding somewhat peevishly, 'I'm very tired, you know. I had a late night.'

Holmes chuckled and rubbed his hands together.

'My dear fellow,' he said, taking his pipe from his mouth and surveying me with mock innocence, 'you seem to be drifting into dissolute habits. It's not like you to refuse an offer of breakfast.'

I rolled out of bed and snatched my dressing gown.

'It's not like you to exhibit such tender care over my eating habits.

You

have not been seen at breakfast for the past five days. I think I'm entitled to an explanation.'

'My dear Watson,' he said, turning to the door, 'an explanation you shall have. Over breakfast.'

Hastily I thrust my feet into my slippers and stumbled after him, knotting the cord of my dressing gown and wincing as a sudden stabbing pain attacked my temples.

'I had a visitor last night,' said Holmes as he descended the stairs ahead of me. 'If you had not been out at your club, you would have been witness to the beginnings of what promises to be rather an interesting case.'

I forebore to correct him concerning my whereabouts of the previous evening, and followed him into the living room, which had, I noted, already ceased to bear any trace of my attempts to tidy up. The breakfast table, laid with Mrs Hudson's customary primness, was as always a salutory reproach to its surroundings.

Holmes sank languidly into his armchair and watched me as I approached the table and poured us both some coffee. I noted that his face was gaunt and pallid, testifying to his unhealthy life of the last few days. I placed his cup beside the place laid for him, and drew up my own chair a little more abruptly than was necessary, causing the china to rattle. I was determined that he should at least breakfast properly before setting out on any investigation.

'Well?' I enquired tersely as I helped myself to bacon and eggs. 'Who was he? The visitor?'

Holmes smiled as he rose from the armchair and approached the table.

'She, Watson, not he,' he corrected gently. 'My client of last night was a young woman, who, if you had been here to see her, would no doubt have made a singular impression upon you.'

'No doubt,' I snapped, setting about my bacon and eggs with gusto. I was in no mood to be teased.

'A most forceful personality,' continued Holmes. 'I should imagine Miss D'Arcy can be quite formidable when she chooses to be. There was a--directness about her manner which I thought would appeal to you, Watson. Not that I can pretend to be

au fait

with your taste in ladies.'

He actually bit and chewed a piece of dry toast. I said nothing, but passed the butter dish and the marmalade.

'She left me three interesting documents which you may care to examine,' he pursued, crossing to the mantelpiece, the dry toast still in his hand. He took a small pile of papers from the shelf and put them down on the table beside my plate. He remained standing beside me, nibbling at his toast absent-mindedly. I put down my knife and picked up the yellow envelope that lay at the top of the pile. I extracted the telegram and read it while working my way through a mouthful of bacon.

It was addressed to Miss Maria Kirkpatrick, of Camberwell Grove, was postmarked Kensington and dated the 16th of January. The message was short and to the point: 'COME AT ONCE NEED HELP MOTHER', with no stops and no signature.

'I thought you said the young lady's name was Miss D'Arcy,' I said, when I had swallowed enough to make enunciation possible.

'So I did. This telegram is addressed to Miss D'Arcy's companion, with whom she lives. Upon receiving it, Miss Kirkpatrick apparently made a hasty departure from the house, and Miss D'Arcy has not seen her since.'

'Well, that is reasonable enough, surely, if her mother needs her so urgently. Has she not enquired for her at her mother's house?'

Holmes clicked his tongue impatiently.

'It is not quite as simple as that, my dear Watson. Not only has Miss D'Arcy no idea where her companion's mother lives, but she was, until the advent of this telegram, completely unaware of her existence. Miss Kirkpatrick had apparently always given the impression that her mother was dead.'

I put down the telegram and took a gulp of coffee.