My Father Before Me (24 page)

Read My Father Before Me Online

Authors: Chris Forhan

â Part V â

Silence and Song

54

Yes, Kevin was writing. It was all that mattered to him, it seemed. Was there something about our being the sons of a father who killed himself that caused us both to turn to poetry? The relationship between the two things is covert, but it exists. For millennia, a father's job has been to show his sons how to live; our father neglected that jobâor he unintentionally took on the opposite task, teaching us that the value of life is questionable. If life had value, if life was worth living, that value and worth were surely present in our own lives, present within us. Poetry, we were discovering, was a way to let those things have their say.

At the top of a narrow, creaky back staircase, in his cramped apartment above a garage, Kevin was staying up through the night, sipping cheap booze, smoking, thumbing through books of poems, and clacking away at his typewriter. Like Keats, like Rimbaud, he breathed poetry, or bled it. This was not a pose; he was not pretending. He was young and in love with what language could do. He was reading Shakespeare, Donne, Blake, Whitman, Stein, Stevens. He was giving himself over to impossible projectsâdevoting months and months, for instance, to the composing of nine-line stanzas in which each line contained exactly nine syllables. He was getting a music into his mind and into his muscles. He was trusting a hunch: if he followed poetry into the dark, followed it as far as it could take him, it might illumi

nate that darknessâproviding a temporary light, perhaps, but a true one. Fiddling with syllables until they sang, turning a line just right to make a sentence's rhythm and sense dance, causing a word to knock softly, like a billiard ball, against another it had never encountered: these might be the means of an alchemy by which he could create something new in language, something that breathed a pure breath, something that could sustain his life or deepen it.

And he was only nineteen, only twenty, twenty-one, and he was my brother, he was good, he was on to something, and the feelings in his poems were ones that I felt, too, and the thoughts were those that, dimly lit, flitted within my own skull but that I could not articulate. He wrote a poem that began “I'm head bent dreaming on the keys / Of any way I might approach you.” Who was that “you,” that someone “scraping a thick grudge” off his walls? That sounded familiar. And that house with “an ambulance parked outside,” someone “sleeping locked in his car,” the glass “all fogged up inside”âI knew that house. I knew the person in that car.

Before my eyes, my brother was making poetry out of life, out of his life, out of mine, making a life that mattered by making poetryâby trying to get at the truth, however murky, and put it into words. It didn't seem such an odd and lonely thing for me to try to do the same.

Perhaps, had our father grown old, he would have spoken to his adult sons of his doubts about God and about himself. Perhaps he would have shared with us his sense of uncertainty and unease about the choices he had made, and about the choices he was making. Perhaps there was some poetry in him. But the father we knew, if he had such feelings, kept them to himself. Outwardly, he remained a man who followed a path of unwavering certaintyâof duty and hard work, of belief that such things bring the rewards of material comfort and social acceptance, and maybe belief that duty and hard work are their own reward: that they are, in themselves, an unquestioned good.

Following such a path, however, can distract a man from himself, from desires and fears and misgivings that, ignored too long, might destroy him. Kevin was taking the opposite path: one of loyalty to his own ambivalence and uncertainty and to his suspicion that the tentative truths he stumbled upon through his own experience had more merit than the rigid ones he had been instructed to believe. He would not follow custom out of fear or courtesy, as our father might have done; he would try to let his own intellect and curiosity guide him, even if they guided him into difficulty and mysteries. He cherished wonder and possibility, and he understood that they are nearer cousins to skepticism than to faith. As I was beginning to do, he was finding in poetry the satisfactions that were not present for him in religion. If poetry and religious faith are similar in attempting to comprehendâor at least frame or point towardâeternal mysteries, poetry could be of use in a way that religion isn't: it is fluid, shifting; its images and forms change; its instinct is to move in order to hit a moving target.

Like my brother, I was addicted to the intoxication that cameâoccasionally, unexpectedlyâin the writing of a poem: the feeling of being outside of time, of floating amid scatterings and fragments of thought that, if I was sufficiently patient and self-forgetful, might suddenly cohere into a shape that surprised and delighted me with its rightness. Sometimes, in a few lines, I felt that I had pinned existence to the mat and it had given up its secrets. The feeling was fleeting, but it did not seem untrue for being so. Maybe it was true because it was fleeting, the quick glimpse of a fact that would blind me if I stared at it too long. What mattered most to me about the poems I was readingâand, I hoped, those I was writingâwas a sense of the strangeness and mystery and beauty of our being here in the first place, of this place itself being here.

Nowhere else in my lifeâsave, perhaps, in late-night conversations I was having with Kevinâdid I feel that this splendid bemusement,

this sacred astonishment, was honored. Only in poetry, only in poetry. Of course, the poems I was writing were horrible: inadvertent hodgepodges of the styles of whichever poets I had fallen for lately, with so many disparate, wispy ideas swirling about and sinking within them that they were muddlesâincomprehensible to anyone but myself. But I was not aware of their faults. I was an initiate, blind with enthusiasm.

I was also incapable of being as wholly loyal as my brother was to this path. Without being entirely aware of it, I was beginning to forge my own way between my brother's and my father's, maybe a way that would prove impossible. I was writing poetry, but I was not making the activity central to my life. Like my father, I would go to college, then immediately enter a conventional career, the kind that had nothing to do with poetry, the kind that, in years to come, I might mention with breezy assuredness to strangers, and they would nod agreeably, with genuine interest, and not knit their brow and purse their lips anxiously.

What career would I enter? What would I be? I thought of these as identical questions. I decided I would be a television newsman. I had always liked watching the news and thinking about itânot just the stories but the way they were presented. I had spent an August evening four years before pointing a microphone at the television, recording the coverage of Nixon's resignation on a cassette tape. I had joined the staff of my junior high newspaper, writing up the exploits of the basketball team and the hiking club. Thinking it would be cool to be on the radio, I had turned high school into a three-year broadcasting apprenticeship. Without planning to, I had been preparing for a career in broadcast journalism. A TV newsman: that was an authentic, respectable thing to be, wasn't itâa fixed identity in which to cloak myself? Poetry felt essential to me, but it was private; it came alive in the off hours, in the dark, and, because its rewards were altogether internal and its pleasures unmitigated, it felt a little wicked. I would keep it to myself.

I decided to attend Washington State University, an easy choice. The school was far enough from homeâthree hundred miles away, on the other side of the Cascade Mountains, surrounded by the rolling wheat fields of the Palouseâthat I would feel truly on my own there, as I yearned to do, and WSU had a good broadcast communications program. Also, I could afford it. I didn't have money to attend a private university or an out-of-state school; at WSU, I would pay in-state tuition, and I'd have a little extra money every month from scholarships. I would also receive an accidental gift from my father: because he was dead, the Veterans and Social Security administrations would send me a small check every month.

Beyond that, though, I needed a little more cash. I needed a part-time job. As soon as I arrived on campus, I auditioned to join the staff of KWSU, the university's National Public Radio station. I was hired. Within a couple of years, I would be back working the shift I knew from high school: I would be the early-morning announcer, hosting the local segments of the national

Morning Edition

program.

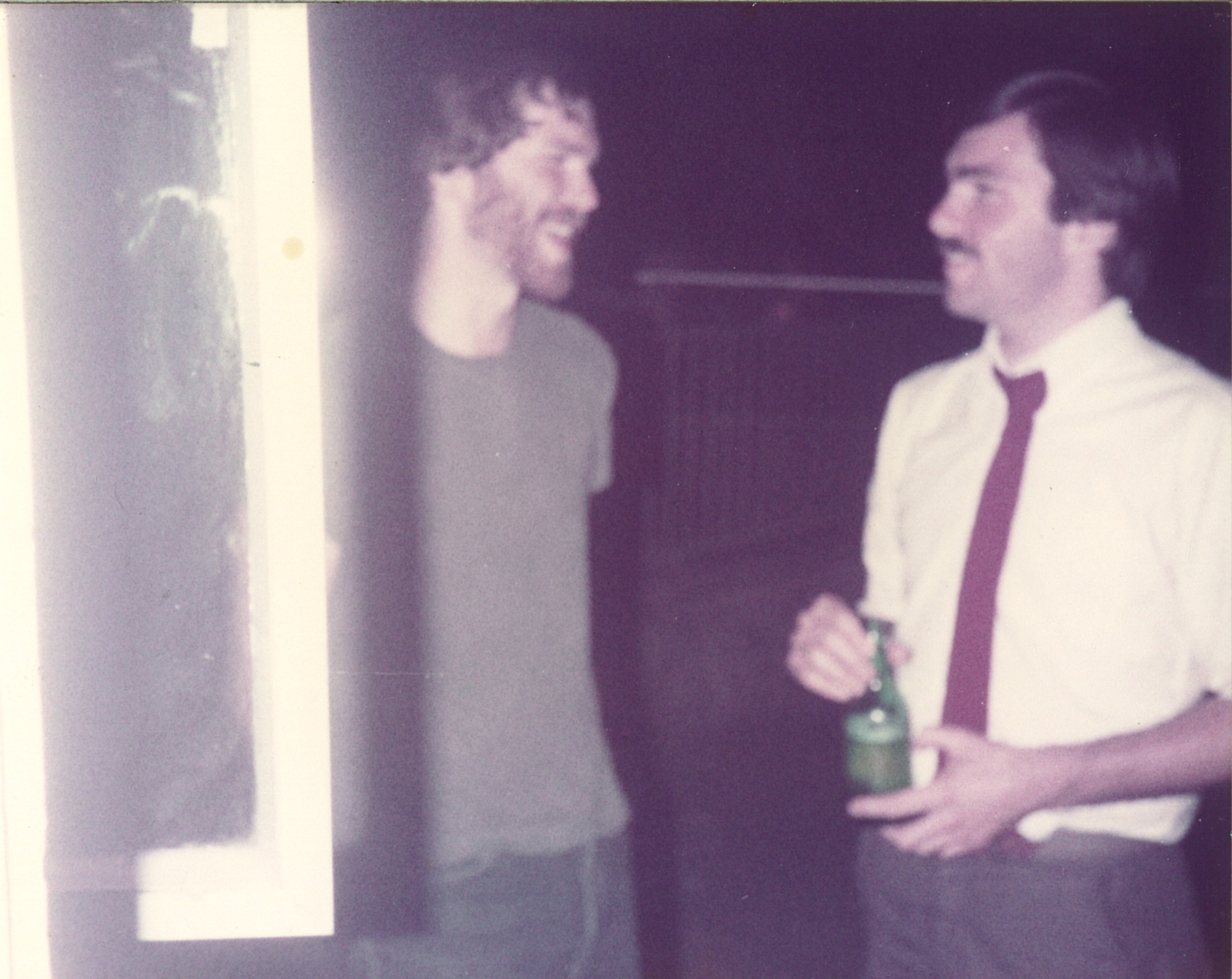

As a communications major, I learned to write crisp, clear news copy; I learned to edit audio- and videotape; I learned about the Fairness Doctrine and landmark Supreme Court free-speech cases. With my cassette recorder in tow, I interviewed professors of veterinary medicine and geology for the radio station. When an eccentric local postal employee and his accordion were hoisted by crane one hundred feet in the air, where he played a polka while hanging by his ankles, I recorded the reactions of pleasantly baffled bystanders. For the student cable television channel, I yanked on my big boots and slogged through the snow with a cameraman to interview a pig farmer; I knotted a necktie, pulled on a sweater and jacket, and co-anchored the weekly newscast, becoming practiced at reading from a teleprompter and sitting without slouching.

But two buildings away, I was taking English classesâmore of

those, finally, than communications courses. The summer after my freshman year, I stayed in town and signed up for an early-morning class in British Romantic poetry. It was taught by a young, silver-tongued Welshman who arrived every day bleary-eyed, stray locks of dark, unwashed hair plastered on his forehead, wrinkled black vest askew on his shoulders, thermos of steaming coffee gripped tightly in his hand. How long had he stayed up the night before? What had he been up to, and what had it to do with the words he recited to us so gravely, nearly in a whisper?

Huge and mighty forms . . . were a trouble to my dreams

.

What the hand dare seize the fire?

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.

Late at night, hunched over my desk, studying a page illuminated by a tiny downturned cup of lamplight, I felt romantic, too.

Here I

am,

alone but not lonely, reading poetry, the poetry of the great dead, poetry ready to reveal to me the big secret, if I can only find it.

With a ruler and a fine-tipped red pen, I underlined slowly, deliberately, the lines I felt I would need to return to.

A sense sublime / Of something far more deeply interfused. Where but to think is to be full of sorrow.

On my own, browsing the shelves of the university bookstore, I stumbled upon Charles Bukowski and began writing skinny little poems about flies and grimy undershirts. I found Sylvia Plath, and my poems became outlandish, compact, and explosive; they borrowed her energy but none of her control. The “secret heaven-zoo” I mentioned in one addled rant of a poemâwhat was that? I know that I was thinking of a girl back home whom, just before leaving for college, I had befriended and ineptly kissed. What I imagined she had to do

with secrets and heavens and zoos, I haven't a clue. In another poem, I knew whom I was thinking of when I wrote, “It's you face down in a / saltwater marsh, / your barrel smoking,” but I let Plath do the talking: “God, Daddy, it's you.”

Were my poems really poems? Were they good? I sent some to my mother, and she wrote back, “I like your poems. They are so somber, though. Do all poets have to be sad or philosophical?” Kevin was encouraging about my writing, but he loved me; he was obliged to be nice. There had to be a poetry professor somewhere on campus. I decided to track him down.

Alex had arrived at WSU only a year before I did. He was quiet and serious and young, still in his thirties, with one book of poems out from a small press. He had studied at the most prestigious MFA program in the country, the Iowa Writers' Workshop, but he was ambivalent about the notion that the writing of poetry could be taught. One day, in the poetry-writing course I had enrolled in, halfway through class he paused. He leaned back in his chair. “Look,” he said, “I can't do this anymore. I don't believe in this kind of class. It's over. No more workshop.” In the silence that followed, we all looked at one another. Was he kidding? He wasn't. Alex proposed that, class being over, we should repair to a nearby pub for drinks and sandwiches, so we did.

Poetry, he was reminding us, is too important, too wild and weird, to be institutionalized and commodified. Its origins are secret, its powers inscrutable. How could one teach such things? This, I thought, was the teacher for me. He was confirming what I had already begun to feel: that poetry is a delicate and deadly serious matter, a gift that vanishes in the hands of any who would trivialize it. It is not just a subject of study; it is a way of perceiving, a way of understanding, a way of being alive in the worldâor being alive

to

the world. I hadn't enrolled in Alex's class in order to prepare for a career. I had enrolled because I couldn't help myself, because I felt that I might choke on the backed-up sludge of my own

being if I didn't. I needed to be with people who understood my odd urge to write poems, people who would give me permission to keep doing so.

The next week, we students showed up in the classroom at the appointed hour, and Alex was there. He made no mention of the previous week's announcement. Maybe he had changed his mind; maybe the dean had changed his mind for him. I was relieved. I wanted to continue meeting with these people; I wanted, every week, to hand Alex the latest poem I had labored over; I wanted to walk to the English Department office the next day and pick up the dittoâthe typed copy of the students' poems that the department secretary had made. I loved seeing all of our poems collected together in blurry purple ink, our names below them. The ditto was a little weekly anthology, a publication. Its readership was smallâjust usâand the poems were imperfect: that was the point. But we were treating them as poems, as acts of language worthy of being shared and contemplated. For those of us who had until now kept our writing private, this was no small thing.