My Lady of Cleves: Anne of Cleves

Read My Lady of Cleves: Anne of Cleves Online

Authors: Margaret Campbell Barnes

Tags: #Fiction - Historical, #Tudors, #Royalty, #England/Great Britain, #16th Century, #Germany

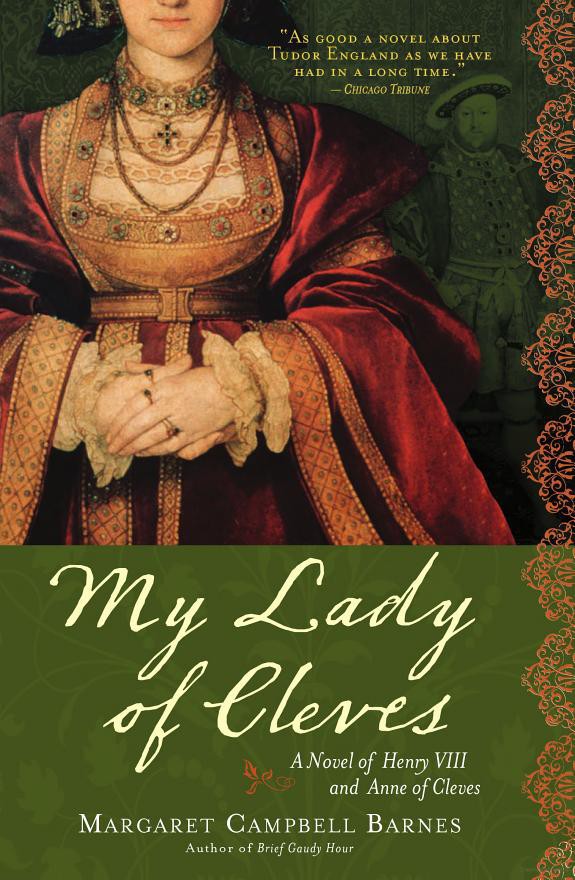

My Lady of Cleves

A Novel of Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves

Margaret Campbell Barnes

Copyright © 1946, 2008 by Margaret Campbell Barnes

Cover and internal design © 2008 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover photo © Corbis

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published by Sourcebooks Landmark, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567–4410

Originally published in 1946 by the Macrae Smith Company.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Barnes, Margaret Campbell

My lady of Cleves : a novel of Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves / Margaret

Campbell Barnes.

p. cm. ISBN-13: 978-1-4022-2078-4

1. Anne, of Cleves, Queen, consort of Henry VIII, King of England, 1515-1557—Fiction. 2. Henry VIII, King of England, 1491-1547—Fiction. 3.

Queens—Great Britain—Fiction. 4. Great Britain—History—Henry VIII,

1509-1547—Fiction. I. Title.

PR6003.A72M9 2008

823.‘91—dc22

2008014776

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

VP 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To

The courage and endurance of all women who lost the men they loved in the fight for freedom.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Most of the remarks made about Anne of Cleves by characters in this book were in fact made by people who knew and saw her. Contemporary descriptions of her appearance are conflicting; but the three existing paintings of her are considerably more attractive than most of the portraits of Henry the Eighth’s other wives. The popular idea that she was fat is completely belied by the neat, gold belted waist shown in Hans Holbein’s three-quarter length portrait belonging to the Musée du Louvre, Paris. His exquisite miniature painted at the same time and now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, is less than two inches in diameter and still lies in the heart of the ivory rose in which it was sent to King Henry. There is a quaint charm about the painting of her by an unknown German artist which hangs in the Great Parlour of St. John’s College, Oxford, in which she wears the same stomacher ornamented with Tudor roses.

Several of Anne’s letters—to the King, to Mary Tudor and to her brother William—are to be found among State Papers, while the Losely Manuscripts contain records of affairs connected with her estates and of domestic purchases made for her by Sir Thomas Carden, her tenant at Bletchingly who appears to have acted frequently as her man of affairs during her enforced “spinsterhood.” Her Will—surely one of the most human and endearing of legal documents—makes delightful reading.

Although she outlived Henry by ten years she chose to remain in England, and perhaps the best proof of the affectionate terms on which she lived with the Tudor family is the place where she is buried. It is the exact spot which Mary, as a character in this book, considered most fitting for her.

M. C. B.

Epsom

, October 1945

1

HENRY TUDOR STRADDLED THE hearth in the private audience chamber at Greenwich. Sunlight streaming through a richly colored oriel window emphasized the splendor of his huge body and red-gold beard against the wide arch of the stone fireplace behind him. He was in a vile temper.

The huddle of statesmen yapping their importunities at him from a respectful distance might have been a pack of half-cowed curs baiting an angry bull. They were trying to persuade him to take a fourth wife. And because for once he was being driven into matrimony by diplomacy and not desire, he scowled at all their suggestions.

“Who are these two princesses of Cleves?” he wanted to know. That didn’t sound too hopeful for the latest project of the Protestant Party. But Thomas Cromwell hadn’t pushed his way from struggling lawyer to Chancellor of England without daring sometimes to pit his own obstinacy against the King’s.

“Their young brother rules over the independent duchies of Cleves, Guelderland, Juliers and Hainault,” he reported. “And we are assured that the Dowager Duchess has brought them up in strict Dutch fashion.”

Henry thought they sounded deadly, and he was well aware that their late father’s Lutheran fervor was of far more value in Cromwell’s eyes than the domestic virtues of their mother.

“Those Flemish girls are all alike, dowdy and humor less,” he muttered, puffing out his lips. The audience chamber overlooked the gardens and the river, and from where he stood he could hear sudden gusts of laughter from the terrace below. He thought he recognized the voices of two of his late wife’s flightiest maids-of-honor. Only yesterday he had heard his dour Chancellor rating them for playing shuttlecock so near the royal apartments. And because he was having his own knuckles rapped—although much more obsequiously—he snickered sympathetically.

“And if I must marry again,” he added, “an English girl would be more amusing.”

It was growing warm as the morning wore on and a bumble bee beat its body persistently against the lattice. But Cromwell was a born taskmaster. “Your Grace has already—er—tried two,” he pointed out, looking down his pugnacious nose.

“Well?” demanded Henry, dangerously.

Naturally, no one present had the temerity to mention that Anne Boleyn had not been a success or to gall his recent bereavement by referring to the fact that Jane Seymour had died in childbirth.

“It is felt that a foreign alliance—like your Majesty’s first marriage with Catherine of Aragon—,” began the Archbishop of Canterbury, who had obligingly helped to get rid of her.

Marillac, the French ambassador, backed him up quickly, seeing an opportunity to do some spade work for his own country. “Your Grace has always found our French women

piquantes

,” he reminded the widowed King, although everybody must have known that Archbishop Cranmer had not meant another Catholic queen.

Henry turned to him with relief. Like most bullies, he really preferred the people who stood up to him. He didn’t mean to be impatient and irritable so that men jumped or cowered whenever he addressed them. He had always prided himself on being accessible. “Bluff King Hal,” people had called him. And secretly he had loved it. Why, not so very long ago he used to sit in this very room—he and Catherine—with Mary, his young sister, and Charles Brandon, his friend—planning pageants and encouraging poets…

“Your Majesty has but to choose any eligible lady in my country and King Francis will be honored to negotiate with her parents on your behalf,” the ambassador was urging, with a wealth of Latin gesture which made the rest of the argumentative assembly look stupid.

“I know, I know, my dear Marillac,” said Henry, dragging himself from his reminiscent mood to their importunities. “And weeks ago I dictated a letter asking that three of the most promising of them might be sent to Calais for me to choose from. But nothing appears to have been done.” He slewed his thickening body round toward his unfortunate secretary with a movement that had all the vindictiveness of a snook, and Wriothesley—conscious of his own diligence in the matter—made a protesting gesture with his ugly hands.

“The letter was sent, your Grace. But, I beg you to consider, Sir, your proposal was impossible!”

“Impossible!” Henry Tudor rapped out the word with all the arrogance of an upstart dynasty that has made itself despotic.

“Monsieur Marillac has just received the French King’s reply,” murmured Cranmer.

“And what does he say?” asked Henry.

Seeing that the prelate had forced his hand and thereby spoiled his bid for another Catholic alliance, Marillac reluctantly drew the letter from his scented dispatch case. After all, he was not Henry’s subject and his neck was safe. “He says that it would tax his chivalry too far to ask ladies of noble blood to allow themselves to be trotted out on approval like so many horses at a fair!” he reported verbatim. And many a man present had to hide a grin, envying him his immunity.

Henry gulped back a hot retort, reddening and blinking his sandy lashes in the way he did when he knew himself to be in the wrong. There had been a time, before that bitch Nan Boleyn had blunted his susceptibilities about women’s feelings, when he would have been the first to agree with Francis. Mary, his favorite sister, had been alive then, keeping him kind. Lord, how he missed her! He sighed, considering how good it was for a man to have a sister—some woman who gave the refining intimacy of her mind in a relationship that had nothing to do with sex. Someone who understood one’s foibles and even bullied back sometimes, affectionately. Mary would have said in her gay, irrepressible way, “Don’t be a mule, Henry! You know very well those stuffy old statesmen are right, so you might just as well do what they want without arguing.” But even if they were right, and he did, it wasn’t as simple as all that, he thought ruefully. For, after all, whatever foreign woman they might wish onto him, it was he who would have to live with her.

“How can I depend on anyone else’s judgment?” he excused himself plaintively. “I’m not a raw youth to go wandering about Europe looking for a bride. I can’t do more than offer to go across to my own town of Calais. Yet see them I must before I decide, whatever Francis says—see them, and hear them sing. I’m extraordinarily susceptible to people’s voices, you know.” The gay, light chatter of the disobedient maids-of-honor still drifted up from the terrace, and in spite of Cromwell’s disapproval it was pleasant enough. “That is why it would be so much simpler to marry an English girl,” reiterated Henry obstinately. But this time he said it in the inconclusive grumble of a man who no longer feels very strongly about anything and only wants to be let alone.

“The young Duchess of Milan has just been widowed,” suggested his cousin, Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, dangling the last Catholic bait he could think of.

Henry, who had just called for a glass of wine, brightened considerably. “Coming from such a cultural center, she should be accomplished,” he remarked complacently, turning the well-mulled Malmsey on his tongue.

“But there is just one difficulty, your Grace,” put in Cromwell.

“Yes?” prompted Henry, setting down his empty glass.

Cromwell cleared his throat uncomfortably. “The lady herself seems—er—somewhat unwilling.”

The vainest monarch in Christendom stared at him in credulously. “Unwilling!” he repeated. He settled his new, becomingly padded coat more snugly about his shoulders and shifted his weight testily from one foot to the other so that he appeared to strut where he stood. “Why should she be unwilling? What did she say?”

But nobody dared tell him exactly what the lady had said; and the Italian ambassador—less hardy than his French colleague—had found himself too indisposed to be present.

Henry glared at them like a bull that has been badly savaged. It was beginning to be borne in upon him that he was no longer the splendid prize that had once fluttered the matrimonial dovecotes of Europe. So he blustered and blinked for a bit to hide his embarrassment and everybody was glad when an ill-aimed shuttlecock created a diversion by smacking sharply against a window pane.

The drowsy bumble bee was still banging its fat body against the inside of the glass, trying to get out. Henry wanted to get out, also.

The room was too full of contentious people and the clever court tailor who had designed the widely padded shoulders of his coat had considered only the slimming effect and not the heat. His shoes, with the rolled slashings to ease the gout in his toes, shuffled a little over the broad oak floor beams as he went to the window; but he still moved with the lightness of a champion wrestler. He pushed open a lattice and stood there in characteristic attitude, feet apart and hands folded behind his back beneath the loosely swinging, puff-sleeved coat. He had turned his back on the dull, musty world of diplomacy, and the world outside was alive and fresh. The wide Thames sparkled at high tide. On the grass immediately below, four or five girls in different colored gowns flitted like gay butterflies as they struck the shuttlecock back and forth.

With the outward swinging of the window their voices had come up to him, clear and strong. There was a slender auburn-haired child who laughed as she ran, and her laughter was like a delicious shivering of spring blossoms. Even his grave, embittered daughter Mary—pausing on her way to chapel to watch the forbidden game—smiled at her indulgently and forbore to reprimand. Seven - teen the girl might be—and, judging by her delight in the game, quite unsophisticated and unspoiled.

Henry wondered why he had been stuffing indoors all morning, when with a touch of his hand he could open a window onto this enchanting world of youth. And what would he not give to re-enter it? He, who had known what it was to enjoy youth with all the gifts the gods could shower! Music, poetry, languages, sport—he had excelled in them all. “

Mens sana in corpore sano

,” (a sound mind in a sound body) he muttered, looking back over that splendid stretch of years and seeing, as men do in retrospect, all the high spots of success merged into one shining level of sunlight and strength. Alas, so easily had he excelled that gradually the strong impulses of the body had sapped the application of a fine and cultured mind! So that now, at forty-seven, while still hankering vainly after past physical exploits, he realized that had he developed that other side of himself, life might still mean growth, rather than gradual frustration.