My Life So Far (58 page)

Jack and Carol had the bedroom, dining room, and kitchen on the ground floor, and we shared the living room. Tom had persuaded Fred Branfman, a writer and researcher who had developed outreach materials for the IPC tour, to move from Washington, D.C., into a small room on one side of our front porch, where he slept on a straw mat with his diminutive Vietnamese wife, Thoa. Fred stands about six feet five, and when I would come down in the mornings to take Vanessa to school, I would risk tripping over his feet, which always stuck out past the door.

Off the other side of the porch, a separate door led up a narrow flight of stairs to the second floor, where we lived. It consisted of a bedroom that looked out onto the street with a minute closet and a small bedroom opposite ours for Vanessa and Corey. The kitchen was tiny, with no vent, and when I turned on the stove cockroaches would sometimes run out. I just plowed on, always thinking I’d deal with it later.

There was little privacy. The walls were made of tongue-and-groove slats so thin that if I put a nail in a wall to hang a picture, it would stick right through to the other side (lovemaking was subdued). My father, only half joking, called the house “the shack.”

We didn’t have a dishwasher or a washing machine, so twice a week I would take our clothes to the nearby laundromat. One day, when I’d stepped next door for coffee, someone stole all my clothes, including the silk pajamas I’d worn in North Vietnam.

I set to work brightening up the place with a pregnant woman’s nesting intensity, and in spite of the downside I actually loved being there. This was community living of a kind I had never experienced. Because the streets were so short and the houses so close (and all had porches), all the neighbors knew one another and would exchange sugar, coffee, and gossip. There were kids for Vanessa to play with, and the beach with swings and slides was a block away. Because I could always hear the sound of breaking surf and smell the salt air, living in our home on Wadsworth Avenue felt like a return to the summers of my childhood. We would stay there for close to ten years.

When celebrity friends would visit, they’d usually ask if the lack of privacy and security bothered me. There were several reasons I liked being so accessible: The first had to do with the issue of “coming down from the mountaintop.” Then, when my children came of school age, both went to public schools, and we didn’t want their friends who came over to play to find that we lived differently from them.

Furthermore, my relationship to my profession had changed. I was beginning to feel I could be in control of the content of my films, and this made me care more and want to go deeper as an actress. How can an artist plumb reality if he or she lives in the clouds? Of course, the fact of my being a movie star created an inevitable separation; most people have a hard time overcoming their intimidation around celebrities. But you’d be amazed how much this separation can be minimized, and I really worked at it. It wasn’t that difficult. I’ve always had a high tolerance for what other celebrities might call inconvenience or discomfort.

Also, for me, the security and privacy issue that so concerned some of my more famous friends was not about being accessible to fans. It was the

government

that was the problem. The first year we were in the house (during the Nixon administration), our home was broken into, drawers turned upside down, all our files and papers strewn about, and our phone tapped, and one day an FBI undercover agent posing as a reporter came to interview me in order to confirm that I had been three months pregnant at the time of our marriage. How do I know this? Because I later read it in my FBI files.

In retrospect I wouldn’t have given up the Wadsworth experience for anything, but I no longer believe that it is necessary to prove your political purity by living in a manner that makes your teeth clench. If you can afford to hire someone to help run a comfortable, attractive home, there is nothing wrong with that, as long as you pay a decent wage with benefits and as long as materialism doesn’t become your focus in life.

During my pregnancy, I spent a lot of time doing research for the film that Bruce and Nancy were developing. I traveled to San Diego to interview wives of Vietnam veterans. One told me, “I talk to my husband now, but it’s as if there’s no one there. He’s empty. It’s like I can hear my voice echoing inside him.” A character was beginning to emerge for me to play: My husband goes to war while I remain at home and go through my own changes because of a relationship with a paralyzed vet I meet in the hospital.

I learned a lot from a Vietnam vet named Shad Meshad, who had been a psych officer in Vietnam. He was a friend of Ron Kovic’s, equally charismatic and fearless, and had an intuitive way with troubled vets, who were flooding to the warm climes of Southern California. When I met him he had become an important member of the staff of the largest psychiatric facility for vets in the country, at the Wadsworth VA Hospital in Brentwood, California, one zip code up from Santa Monica. Back then doctors didn’t have a diagnosis for the symptoms Vietnam vets were presenting. It would be several more years before posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) would be recognized by the medical establishment as a complex of symptoms and a specific diagnosis—and only then thanks to the tireless and empathic work of Drs. Robert Lifton, Leonard Neff, Chaim Shatan, and Sarah Haley and Vietnam veterans themselves. But guys identified with Shad. He had established rap (discussion) groups in Venice, Santa Monica, Watts, and the barrio and helped put Bruce and Nancy in contact with many of them.

Ron Kovic invited me to come to a meeting of the Patients’ Rights Committee at the Long Beach Veterans Hospital, where he was currently a patient. He wanted me to hear from other guys about the poor conditions there. It was midday when several hundred people, the majority on gurneys or in wheelchairs, gathered on the lawn behind the paraplegic ward. Ron and another ex-marine, Bill Unger, had had a leaflet distributed announcing that I would be there. In protest there was a counterdemonstration of World War II and Korean War vets, waving flags and singing patriotic songs to try to drown us out.

I don’t remember what I said to the vets that day, but I do recall being totally shocked at what they said to me. The guys from the paraplegic ward told me how their urine bags weren’t emptied and were always overflowing onto the floor; how patients were left lying in their own excrement and would develop festering bedsores; how call buttons weren’t answered and when patients protested they’d be put in the psych ward, given Thorazine, or even lobotomized. Ron had been rolling his gurney around the different wards with a hidden tape recorder, gathering evidence, and journalist Richard Boyle verified these stories while researching an article for the

Los Angeles Free Press.

I immediately arranged for Nancy Dowd and Bruce Gilbert to come down and see for themselves, and everything we heard and saw found its way into the film

Coming Home.

A

s it turned out, the final push to end the war coincided with the birth of Troy. It was 1973. Friends of ours, Jon Voight and his wife, Marcheline, had just had a baby boy, James, and they recommended we take birthing classes with the woman who had coached them, Femmy DeLyser, who lived just south of us in Ocean Park.

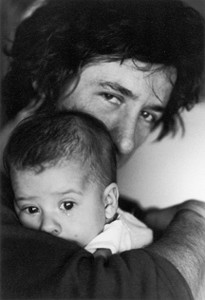

Tom holding Troy.

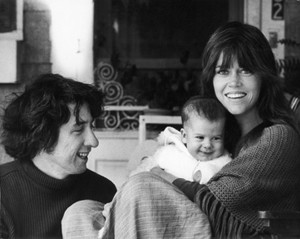

On our front porch with Troy.

(John Rose)

My water broke one morning while I was standing on the porch with Carol. This time I was ready, and this time the birthing was different. For one thing, I was an empowered participant; Femmy had seen to that. No doctor was going to give me drugs unless

I

wanted them; no nurse was going to make me feel she knew more than I did about how it should go. I was awake, Femmy was there with me along with Tom and Carol, and though I begged for pain relief just before I was being wheeled into the delivery room, Troy was born before it took effect, so for all intents and purposes it was a natural birth.

Tom lifted the baby out of me, and I saw immediately in the overhead mirror that it was a boy. They laid Troy O’Donovan Garity on my chest, and I noted with groggy astonishment that he didn’t cry. Tom was crying. I was crying. But not Troy. I’d never heard of a newborn not crying, and I saw this as a sign that his journey through life would be blessed.

During the first few weeks I was very resistant to letting Tom hold or change Troy. I think this was because I was defending my domain as the one who knew what she was doing. This was one area where I, who had already had a child, knew more than Tom—and I wasn’t about to let this go. When I finally did let go, however, I was terribly moved by how tender Tom was with his son and how touched by fatherhood. He would lie naked in bed with Troy on his stomach for hours, just cooing to him. In his autobiography Tom wrote, “Then and there . . . I made a pledge: I would build my life around this little boy until he became a man.” I don’t believe anything in Tom’s life softened his heart the way Troy did. Although Tom and I would divorce sixteen years later, he kept this pledge to his son and has always been a present and involved father.

Almost until the day I delivered, I had continued making speeches against the war on campuses all over California. With my protruding belly, usually draped in a bright purple knit poncho, I looked like the defiant prow of a ship. Within days after Troy’s birth I returned to meetings and speeches, bringing him with me everywhere. I handled the experience so differently from the way I had with Vanessa. A lot of this change was because of Tom: He would not have tolerated leaving Troy, he was against nannies, and neither of us was about to stop what we were doing—so by necessity I had a different relationship with my son than I had had with Vanessa. I was, perhaps for the first time, really showing up for someone.

Troy would nurse and our eyes would lock as he gazed at me across my breast for many minutes at a time. I realized that I was imprinting him with love and that my touch and this prolonged gaze between us were important. I know that for many mothers these things come naturally, but they hadn’t for me—partly because of my own early childhood. As I have learned more about parenting over the years, I see that sometimes when you haven’t healed your own wounds, as I hadn’t, it is painful as a parent to open your heart to a child and you avoid it. My way of avoiding it was to stay busy. I was at the beginning of the process of healing when Troy was born, and the bittersweet part was my awareness and sadness that I was giving Troy something I had not given enough of to Vanessa. She was nearly five years old when Troy was born, and during the first years afterward, she moved back and forth between our home in Ocean Park and her dad’s place in Paris.

T

he escalating scandal surrounding Watergate (many of Nixon’s staffers had been forced to resign) was weakening the administration, which offered us a strategic opportunity to mobilize the antiwar forces IPC had built the previous year. When Troy was three months old, we embarked on a three-month tour. The goal was to put pressure on Congress to cut funding of the Thieu regime in South Vietnam. Troy would sleep in dresser drawers that I padded with blankets and set on the floor by our beds. When I’d make a speech, someone would hold him in the wings until I was through, and occasionally I’d be in the middle of a speech when my milk would let down, and I’d have to hand the microphone to Tom and step into the wings to nurse.

Following the tour, I made my second trip to North Vietnam, this time with Troy and Tom. The purpose was to make a documentary film,

Introduction to the Enemy,

aimed at showing a human side of Vietnam, a view of the people’s lives and stories very few Americans would otherwise ever see or hear. We wanted it to be not about death and destruction but about rebirth and reconstruction. Haskell Wexler, the brilliant American cinematographer whose credits included

Medium Cool

and

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?,

filmed it for us.