My Life So Far (9 page)

Me right after birth, in the arms of the masked nurse.

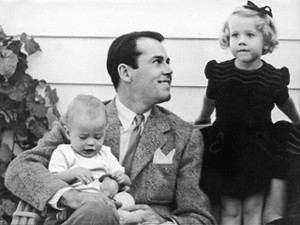

Peter’s come home and I am definitely skeptical. That’s Pan standing behind Mother.

I know he loved me when I was little.

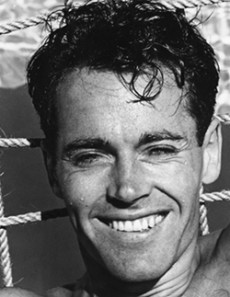

Dad liked me, though. I knew that, especially in the earliest years. I was his firstborn, I had the Fonda look, and I was a tomboy. In the summer, he would take me into his arms, walk down the steps into the swimming pool, and play with me in the water. I would bury my nose in his shoulder on the way down the steps and smell his skin. He always had a delicious musky smell that I loved . . . the smell of Man. Yes, he was happy with me when I was little—and deep down I knew his was the winning team, the one I’d do anything to join.

My first four years were spent living in a spacious house in California, sandwiched between Beverly Hills and the coastal city of Santa Monica. Margaret O’Brien lived down the street in a big white plantation-style house. Producer Dore Schary, whose two daughters, Jody and Jill, would become schoolmates, lived around the corner. Mother had purchased a home for Grandma Seymour a few doors down from ours.

This is how Dad looked when he’d take me into the pool.

(John Swope, Courtesy the John Swope Trust)

Today, the house we lived in belongs to actor/director Rob Reiner and his wife, Michelle. In the nineties, with my third husband, Ted Turner, I attended one of their Oscar-viewing parties in a new wing of the house that was the projection room. During a break in the ceremonies, I got Rob Reiner’s permission to wander around the house, seeing how much of it I could remember. I walked into the first-floor master bedroom. I knew exactly where I was because the nicest memories I have of being with my mother took place right there at around age four. She would sometimes take me into her bed in the mornings and read me Grimms’ Fairy Tales and the Oz stories.

Mother spent a lot of time in bed even then, and she had one of those rolling hospital tables that would swing over the bed, tilt to hold reading material, and flatten to receive a breakfast tray. She always had beautiful lacy bed jackets and peignoirs, and soft, silky sheets. Her bed was a nice place to be, and by then I guess I had forgiven her for preferring my brother. The fairy tales and children’s poems she read were illustrated by Maxfield Parrish: colored plates of princesses, sorcerers, fairies, and knights brandishing swords to slay fire-breathing dragons. There was a dreamy, haunting quality about the illustrations, equally romantic and frightening. Even though the illustrated plates appeared only once every chapter, the images were so evocative that they would draw me into their dark, languorous world. Mother’s voice would disappear and I would

become

the story, like a movie inside my head.

Why, I wonder, have these stories, filled with sadness, loss, and danger, lasted through the ages? Why did the writers put in things that can frighten children? But if I put myself back then, back into my four-year-old mind, I think that I, like all children, already had an existential understanding that life is dangerous and there is sadness—and rather than lying about these realities, these stories and images externalize them so that we can see and acknowledge them but not die from them.

Starting in the final years of the thirties, right at the end of our block lived the Hayward family. What was rather extraordinary about this was that Mrs. Hayward was none other than Margaret Sullavan, my father’s first wife—the woman who had broken his heart. Mr. Hayward was Leland, my father’s agent. The Haywards had three children, Brooke, Bridget, and Bill. By now, Sullavan had become a big star of both stage and screen, but her role as mother to her three children took precedence. Leland’s client list included not just my father but every major star in Hollywood: Greta Garbo, Jimmy Stewart, Cary Grant, Judy Garland, Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers—and on it went. Inevitably, the Hayward kids were over at our place or we were over at theirs. But during all those years my parents were invited only

once

to the Haywards’ for a dinner party, an invitation my mother never reciprocated. I intuited that something in Dad became more alive when Sullavan was around, and if

I

picked it up, Mother must have.

I have a vivid image of Margaret Sullavan, from the way she looked to the deep, husky quality of her voice. But what impressed me most about her was how athletic and tomboyish she was. Dad had taught her how to walk on her hands during their courtship, and she could still suddenly turn herself upside down—and there she’d be, walking along on her hands. At the Hayward house there were always lots of games and laughter. Mother laughed in those days, too, and had many friends, but she tired easily and was not at all athletic. She would dress me up in frills and pinafores, which I hated, but Mrs. Hayward let her kids wear comfortable clothes and she herself wore old slacks and sandals.

The other major factor in my life after Peter’s birth was the impending war. I remember Mother and Father leaving home to go watch the night sky for enemy bombers. This was something patriotic civilians volunteered to do: “keep our skies safe.” The governess would get me all dressed for bed and then let me go downstairs to say good-bye as they walked out the door. I was filled with dread. What if they got bombed and didn’t come back? The fact that the adults would try to reassure me by explaining that we weren’t actually at war yet and certainly weren’t being bombed made no difference. If there were no bombs, what were they scanning the sky for? It made about as much sense as the “finish your plate, think of all the starving children in China” routine. If they’re hungry, send

them

the food, right? I mean, where’s the logic? Adults!

CHAPTER FOUR

TIGERTAIL

I am much too alone in the world, and not alone

enough to truly consecrate the hour. . . .

I want my own will,

And I want to simply be with my will,

As it goes toward action . . .

I want to be with those who know secret things

Or else alone.

—R

AINER

M

ARIA

R

ILKE,

“I Am Much Too Alone in This World,

Yet Not Alone”

M

OTHER AND

D

AD

decided around 1940 to buy nine acres of land on the end of a dirt road called Tigertail because of the way it wound around the mountain. That part of the Santa Monica Mountain range was all beige undulations like a woman’s body, the curves blanketed in native grasses and tattooed with occasional scrub oaks and sturdy California oak trees. On the steeper slopes, red-barked manzanita, chaparral, and sage grew thick, and from the canyon bottoms arose the California sycamores, their thick, gnarled trunks and mottled bark looking like Maxfield Parrish’s trees where gremlins live. You won’t see this today—those rolling hills are covered with houses now, and the exotic, imported landscaping that surrounds them has all but obliterated the beige California of my girlhood.

My parents built a home there that was as close to a Pennsylvania Dutch farmhouse as was possible, given that this was Hollywood and Mother was, well, Mother.

I

t is conceivable that their marriage was fairly happy, although the abrupt change in lifestyle must have been hard on Mother. She went from being a lively New York City society widow, in charge of her own life, to being, at least at first, the stay-at-home wife of a constantly working movie star who left her alone a lot and wasn’t very good company when he was there.

After several years, my father began having affairs. Mother seems to have known nothing of this until one of the women filed a paternity suit against him. Mother used her own money to buy the woman’s silence. Pan recalls, “I remember vividly the heavy atmosphere and anguish in Mummy’s bedroom . . . her talking with Grandmother.”

I am quite sure that this crisis was only the most dramatic of the problems in their marriage. Dad was so emotionally distant, with a coldness Mother was not equipped to breach. Grandma Seymour told several family friends how her daughter would beg him, “Talk to me, Hank, tell me what I’ve done wrong. Say something, anything.’ But he would never say a word.” I don’t believe he meant to be cruel. Perhaps it was the chronic depression that ran in the Fonda family.