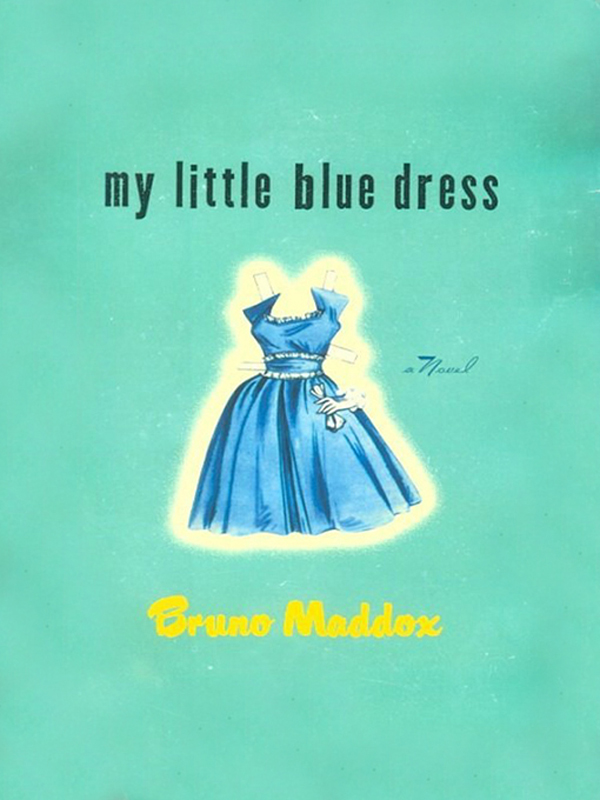

My Little Blue Dress

Read My Little Blue Dress Online

Authors: Bruno Maddox

1900â1909

THE RIGHT SORT OF BEAUTIFUL

1910â1919

ME AND THE GLOBE AFLAME

1920â1929

A DANCE TO THE MUSIC OF JAZZ

1940â1949

THE GLOBE AFLAME AGAIN

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Â

My Little Blue Dress

Â

A

Viking

Book / published by arrangement with the author

Â

All rights reserved.

Copyright ©

2001

by

Bruno Maddox

This book may not be reproduced in whole or part, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission. Making or distributing electronic copies of this book constitutes copyright infringement and could subject the infringer to criminal and civil liability.

For information address:

The Berkley Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Putnam Inc.,

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014.

Â

The Penguin Putnam Inc. World Wide Web site address is

http://www.penguinputnam.com

Â

ISBN:

978-1-1011-9105-7

Â

A

VIKING

BOOK®

Viking

Books first published by The Viking Publishing Group, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc.,

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014.

VIKING

and the “

V

” design are trademarks belonging to Penguin Putnam Inc.

Â

Electronic edition: June, 2003

To B.M.

Thanks for everything.

1900â1909âS

IMPLE

V

ILLAGE

C

HILDHOOD

long afternoons in long grass; sunsets to die for; constant tink of blacksmith's hammer; voice of mam calling home for tea, etc.; wins Queen of the May competition thereby getting life off to Good Start

1910â1919âP

UBERTY

+ W

AR

jealous of friend's breasts but then gets her own; loses virginity in sun-dappled clearing; humankind loses its innocence in trenches of WW1; knits blue dress to kill time while deflowerer is away at war

1920â1929âJ

AZZ

A

GE

dances around in shapeless bell-shaped hat; drinks booze from silver flask; goes to see psychiatrist; admires modern-art painting

1930â1939âP

REWAR

E

RA

slope of foreboding; storm clouds gather over Europe; humankind peers forward into blackness . . . sees only void

1940â1949âW

ORLD

W

AR

2 bombs; rubble; greenish clothing; bittersweet partings and reunions; intensity

1950â1959âF

IFTIES

postwar prosperity; moves to America; finds self awash in vacuum cleaners; home-movie cameras; ice-cream machines, etc.

1960â1969âS

IXTIES

beatles warhol dylan etc.; then hippies

1970â1979âS

EVENTIES

oil crisis; orange trousers

1980â1989âE

IGHTIES

wads of money; cackles while smoking cigar and talking on cellphone the size of brick

1990â1999âN

INETIES

cellphone much smaller; computer everything; millennial foreboding

2000âpresentâN

EW

Y

ORK

life in Chinatown; nice young man; i would like to die now please

Coming of Age

Coming of AgeTHE RIGHT SORT OF BEAUTIFUL

L

IKE A LOT

of little girls back then in that part of the world I viewed the future with a certain lack of enthusiasm, though for a different set of reasons than the rest of them.

The problem for all the other little girls was that these were the early years of the Twentieth Century and we lived in a particularly rural section of England where, even by the standards of the day, people held very fixed and depressing ideas about how a little girl's life was supposed to unfold. Unless you were bedridden with polio or some other disease they would generally allow you an idyllic country childhoodâlots of daisy-chain making and cramming berries in your mouth as fast as you could pick themâthen even a fairly languid and sun-soaked early teenage, but if by

seventeen

years old you weren't married to a farmer, hiding his wage packet in case he drank away its contents, then you were officially declared a Spinster and you had to go start

work immediately in the windowless village dairy where the hours were long and the wages microscopic.

If this all sounds familiar to you, I can't say I'm surprised. It does sometimes seem these days as if every other book that gets published is an old woman's memoir that begins exactly like this one is beginning: back in the gaslit, horsedrawn days of yore with the author complaining about how tough it was to be a little girl and I would be reluctant to add to that steaming pile of volumes if I didn't feel that few of them have even come close to capturing the true horror of what it felt like to wake up every morning in an unheated house to the knowledge that your future was a) set in stone and b) bleak. It was one of the worst feelings you can imagine.

Or so I gathered. Thanks to a fluke of genetics I wasn't personally faced with either of the grim scenarios outlined above but was destined instead to be elected “Queen of the May” at our annual village “fayre” after which, if tradition held, the world would essentially be my oyster.

I

T WAS ALL

due to happen in 1905, when I would be five, my first year of eligibility. For two weeks that May, after my coronation at the opening ceremony, I would strut among the various tents and stalls of the fayre in a phalanx of local dignitaries, snipping ribbons, awarding prizes, posing for line drawings and then, after declaring the fayre officially closed, retire to a chair in our living room where I'd spend the rest of the summer listening to pitches from people who wanted to adopt me and/or give me money.

There'd be a lot of them, if tradition held: rich old women craving companionship, distinguished local artists begging to set me up in a cottage and use me as a “muse,” savvy local

businessmen offering me largish annual sums to endorse their emporiums . . . and the choice of a benefactor would be entirely up to me. This wasn't one of those situations like in an old English novel where the gorgeous little yokel girl gets set to live with the evil rich family so that her real family can buy food. My parents were relatively well off, owing to me da being foreman of an enormous crop-processing device known as a “fangle,” and they had no other children. According to me mam they “just wanted me to be 'appy,” which by any sensible reckoning I probably would be. I mean, think about it. I was going to be rich, at six, living a life of unrelenting comfort and leisure that was entirely of my own choosing.

But did this prospect excite me?

No. It depressed me. As stated, I viewed the future with a certain lack of enthusiasm. For the reasons I just explained I'd been an object of extreme resentment to all the other little girls in Murbery since the moment I first ventured down the hill in my perambulator, to the point that by the tender age of three I'd developed a crippling case of social anxiety.

Down at the schoolhouse every day I'd slump low in my chair and pray that I wouldn't be called on to answer a question, because every time I did there'd be dirty looks. When playtime came I'd spend as much of it as possible playing with my only friendâKaren, the daughter of me mam's best friend who had been forced to bond with me during the crucial first few weeks of lifeâand then either hide in the bathroom or stand at the edge of a group of girls, smiling tightly and hoping nobody felt like punching me in the face. Little girls can't punch very hard, famously, but when you are one yourself, when the muscles and bones in your face are as puny as the muscles and bones in the arm of

the little girl who's punching you, it can feel like a block of pure concrete.

And the Queen of the May thing was just going to make it all worse. To start with there'd be the fayre itself, everyone looking at me and making comments on my appearance for two weeks, and then there'd be the rest of my life which, no matter how I ran the numbers, seemed certain to carry me even further away from my only real ambition, which was to one day experience the feeling that had eluded me all my life: the feeling of simply fitting in, of belonging, of being accepted as normal. If I were to leave Murbery, by letting myself get adopted into the aristocracy, then I'd be a permanent, wrong-fork-using oddity, but even if I stayed, as I planned to, and married an only reasonably prosperous local manâas me mam had done after winning the Queenshipâthen I'd never be free of the other little girls, whose resentment of me, one could just tell, was likely to deepen rather than wane.

Not that me mam's contemporaries resented

her,

particularly. But that was because me mam had won Queen of the May in the usual fashion, after the usual hard-fought and suspenseful contest. In 1905, everybody knew, there wasn't going to be any suspense, nor even any reason for any other little girl to enter. No one else had even a prayer of winning.

The problem was my looks. Not only was I far and away the most classically quote unquote “attractive” girl in Murbery, even as a three-year-old, but mine also happened to be the exact brand of doll-like English beauty that the judges of the contest had historically rewarded, featuring: a snub little nose; a slim, athletic build; and a cloud of golden ringlets that bounced behind me when I walked.

What really clinched it though was my size. The whole point of the village holding a springtime fayre in the first place was to celebrate the return of the Lifeforce after the long cold months of Winter. Consequently the Queen of the May, whose job it was to be the fayre's symbolic figurehead, was always either a) what was known as a “Slut,” an alluring and voluptuous fifteen-year-old to symbolize fertility and bumper harvests etc., or b) an “Infant,” meaning a little golden-haired angel child like myself to symbolize birth, and freshness, and that whole other side of the Lifeforce.

Nowhere was it

written

that some medium-sized eleven-year-old couldn't waltz along and scoop top honors; it just never, ever happened. Queen of the May was always either an Infant or a Slut, and in the years the judges elected an Infant they invariably went with the smallest one available, which in 1905 looked set to be me by about eight inches. The Sluts weren't going to be anything special that year, it was widely accepted, so even if I'd been normal height I think I would have still had victory in the bag. But my size put the thing beyond doubt. Barring a freakish growth spurt or a disfiguring facial accident Murbery's Queen of the May for the year 1905 was going to me, yours truly, the author of the memoir which you are holding in your hands, and there was absolutely nothing I could do about it. The whole situation was like one of those deceptively toothless Chinese curses: “May you be gorgeous and rich and live happily every after!” Sounded great until you thought about it, and then you realized it was actually a nightmare.

So I tried not to think about it, distracting myself as much as possible with the traditional joys of rural childhood, and I'm glad I did because that really was a fantastic time to be a toddler in the English countryside. Some

evenings even now, when the sunset fills my apartment and makes my possessions go all pink, I find my eyelids fluttering shut, my heart rate decelerating, my mind detaching from its moorings and floating up . . . away . . . away from New York and this high-speed modern world . . . floating back in time . . . over decades and decades and decades . . .

. . . and suddenly it's me and Karen, just like it used to be, tearing over fields in the hours after school, splashing through streams, probing into caves, punching little-girl-shaped holes through the hedgerows as we tried to outrun the dusk and squeeze as much juice from the day as possible before that soul-crushing moment when the voice of your mam came floating over the hills and called you home for your tea. Reader, there was nothing worse, nothing worse than that moment. “That were

your

mam, reet?” you'd say, turning to Karen, straining to ignore the fact that it was

your

name the voice had called . . . but Karen would shake her head, leaving you no choice but to hurl your last egg in disgust at Wee Lickle Davey, the school's smallest boy, whom you and Karen had tied to a tree, and set off on the long plod home. With the earth between your feet going all shimmery and invisible in the fading light, the breeze off the ocean beginning to buffle in your ears, you slowly made your way back toward Murbery. Suddenly

whoosh

. Miles away down the coast you watched the gaslamps of Hughley flame on for the night, followed in quick succession by those of Clee . . . then Waxford . . . then Bliffington . . . and finally Froom: until it was like someone had taken a string of burning pearls and laid it out along England's ragged coast, the beauty of which made you sadder than ever.

But then there was your house. And there was the hearthlight wiggling in the windows, and you picked up

speed in spite of yourself, trotting as you hit the slope of the Hill, then sprinting up it, and then eventually just

erupting

through the door of the kitchen to dive at your mam's legs. “Oh look at the state o' thee!” she'd squeal as you hugged her, and with her tutting her exasperation you would break away, peeling off your muddy brambled pinafore as you tore up the stairs, then scrambling instantly back down again in flannel pajamas to find the table already groaning with thick-cut slabs of ham, crusty rolls of water bread, a jug of lemon cider with the anti-insect piece of burlap still stretched across its mouth, dumplings, and gravies, and salads, and pastes, authentic local cheeses in coats of greasy greaseproof paper and a great tureen of steaming turnip with the little flecks of wild walnut winking at you from deep in the pale green depths . . .

Yes, those were magical years to be a tiny little girl, growing up in the depths of the English countryside.

But then, of course, boom.

All of a sudden you were five.