My Sergei (34 page)

Authors: Ekaterina Gordeeva,E. M. Swift

Marina had brought Polaroids of all the different poses that Sergei and I had done in our programs over the years. From the

Rodin number. From

Romeo and Juliet.

From

Moonlight

Sonata. All romantic poses. The skaters paired up, and everyone assumed one of these poses, all of them taking it very seriously.

I knew right then they would skate perfectly the next night.

Vladislav Kostin, our costume designer from the Bolshoi Theater, had come, and he created the white dress that I would wear

in this finale. Tatiana Tarasova also was there. I was feeling so much better after seeing everyone, feeling that they’d come

to support me, come to Hartford for Sergei, to do what they loved to do. And I knew that they’d wanted to come with all their

heart. I can’t describe what this meant to me, except to say I didn’t even worry about the show anymore. The only thing I

was worried about was the dinner beforehand, because I knew I couldn’t invite everyone. My house was too small, and I didn’t

want anyone to be upset.

We rehearsed again the next day at the Hartford Civic Center, where the show was being held. Marina stressed everyone out,

which was unusual. In the Lillehammer Olympics she was also nervous, but she’d kept herself composed. Here, she was nervous,

but also weak. She couldn’t decide on things, not even on which dress I should wear, which wasn’t like her. She had been so

sad since Sergei’s death, like a flower that had so much energy, but now had lost its bloom. Marina did find the words, however,

to give me strength before I skated that night. “Just trust Sergei,” she said, “and he will help you.”

I wasn’t in the opening processional number. I was waiting behind the curtain, not watching for fear that I would cry and

lose my composure. When I heard the music of

Moonlight

Sonata, so many memories came back. I found myself going through my movements for our free program from the 1994 Olympics.

Here Sergei throws me. Here we spin. Here we cross over. Here we do the side-by-side jump. I couldn’t stop myself. I didn’t

want to stop myself. I felt Sergei’s spirit was beside me right then.

As the time neared for my solo number, I thought about the words Sergei used to say to me when we were getting ready to skate.

We always kissed each other before we skated, we always hugged and touched each other. Now, in the tunnel, waiting to go on

the ice, I didn’t have anyone to touch or kiss. It was a terrible feeling to be standing there by myself. Only Dave, the tunnel

attendant for Stars on Ice, was there watching, and I could tell he was thinking the same thing: How sad to see her standing

here without Sergei.

Then I thought of what Marina had said: Just trust Sergei, and he will help you. It felt like there was a rock in my throat,

and I knew if I started to get emotional, I’d never be able to stop.

But as soon as the Mahler music started to play, and I skated out into the darkened arena, the bad feelings went away. The

lights rose, the people started to applaud, and I had a feeling I’d never experienced before. I’d been worried that I’d be

lost out there by myself, that I’d be so small no one would see me. But I felt so much bigger than I am. I felt huge, suddenly,

like I filled the entire ice.

As the people clapped at the beginning of the program, I wondered whether I should stop. I wanted to thank them for coming

from all over the country, all over the world, to think of Sergei. But my legs kept moving. I thought, I can’t stop or I’ll

lose all this magic and power. I just listened to my legs. And I listened to Sergei. It was like I had double power. I never

felt so much power in myself, so much energy. I’d start a movement, and someone would finish it for me. I didn’t have a thing

in my head. It was all in my heart, all in my soul.

I’ll never be able to skate this number as well again. I don’t want to skate it again. It was such a special thing, and I

don’t know if Sergei would help me a second time.

When I had finished, I couldn’t control my emotions. I saw Daria. I saw Sergei’s mother. I saw the people standing and clapping.

I was happy, but I had tears in my chest, and they wanted to fall out. I didn’t want to cry, because it was supposed to be

a celebrational evening, commemorating the happy years Sergei and I had together. But some things you cannot control. And

the other skaters were all standing and crying. They were all so proud of me. I wanted to hug every one of them. And I wanted

to hug Marina, who was standing at the edge of the ice so I would remember which way to exit. She said she was going to wait

until I saw her, and then leave. But she couldn’t leave.

I remember that Marina still looked very, very sad at the end of this number, very drained, which I thought meant I had skated

it well. She just asked for some Visine. Then Daria came up to me and said, “Mom, why did you wrap your arm around your head

when you were skating?”

It was the pose I had used when expressing my misery to God that Sergei was gone. I said, “You didn’t like this pose?”

“No.”

“Okay.” I smiled, hugging her. “I’ll never do it again.”

Marina didn’t talk to me much about the second number, the finale, in which I was skating for Sergei. She said for me to try

to be beautiful, try to skate well, try for Sergei to smile. Try to skate as if to say thank you, Sergei, for having been

my husband, friend, and partner. Remember me always as this beautiful, and I, of course, will remember you my whole life.

Thank you for sharing yours with me.

When I skated this finale, I didn’t feel so powerful. I did, however, feel relaxed and happy, even joyful. Scott was the first

onto the ice, and he invited all the other skaters to join him. The costumes they were wearing were white, and everything

looked so pure and clean and beautiful. Then I skated past them as if to say, Show me what Sergei and Katia used to look like.

That’s when they assumed the poses that Sergei and I had done throughout our career. They held these poses until I got to

the end and turned around, then the next time I passed, it was like I was telling them, Thank you for showing me Sergei and

Katia one last time. Then I destroyed the poses with a wave of my hand.

I skated up to Scott, as if to ask, Can I skate as a single? I think of Scott, not as the king of skating so much as the god

of skating. He’s so natural both on and off the ice. I feel such high respect for him, that if I were to ask anyone for permission

to skate, I’d ask him.

And then I skated a little, and bowed to the audience like in a Russian folk dance. But you know, I didn’t feel comfortable

with this number. I wanted everyone to skate more in the finale. I didn’t want everyone looking at me. The show was for Sergei.

It was his night.

I knew afterward that I was supposed to say something. I thought I should get a speech ready, but as soon as Scott handed

me the microphone, I couldn’t think of any words. I was later upset I didn’t thank enough people. I should have mentioned

more names. But what came out was approximately this:

“I’m so happy that this evening happened, and I’m sad it’s all over. I want to start it over again. I want to thank all of

you, because I know I will not be able to skate here if all of you did not come tonight. I’m so happy I was able to show you

my skating. But I also want you to know that I skated today not alone. I skated with Sergei. It’s why I was so good. It wasn’t

me.”

I started to lose my composure when I began to thank the other skaters:

“I want to thank all you guys. You’re the best. You’re such a good friend. You’re so good. Thanks, Scott. Thanks, everyone.

Thanks, Sandra, Michael, Lee Ann. So many names. Thanks, United States. Thank you

so

much. And I want to introduce you to Sergei’s mother. She came all the way from Moscow, first time to United States. And

she gave me Sergei and I want her to …”

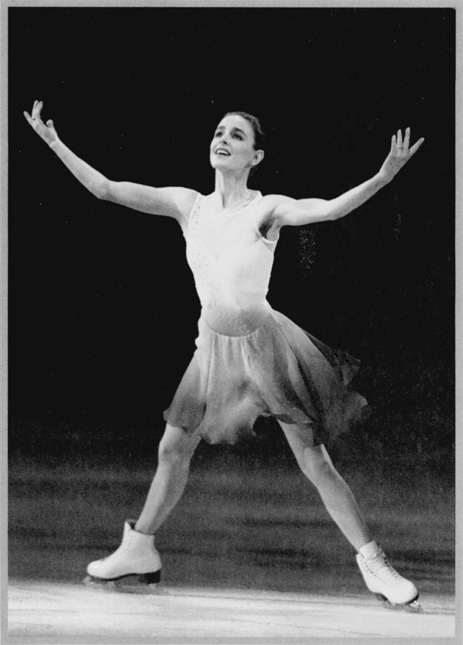

Heinz Kluetmeier

Skating for Sergei.

Anna took the microphone then, and I translated her thanks.

Then I thanked my own parents, who were sitting with Anna and Daria. Then I remembered what I had wanted to say: “I don’t

have enough words, but I also want to wish to all of you: Try to find happiness in every day. At least once, smile to each

other every day. And say just one extra time that you love the person who lives with you. Just say, ‘I love you.’ It’s so

great. Okay? Thanks everyone. Goodbye.”

Time, I have learned, is a doctor. I am finding that the

good days increasingly outnumber the bad ones. My smiles come more naturally. My longing, while it remains, is less acute.

It will always remain, but it’s a room inside me that I no longer feel compelled to visit.

Skating has been the best medicine for me. I love being with the people; I like the training; I like the feeling of being

physically tired after a long practice session. After Sergei died, I lost myself when I was so long off the ice. To come back

to myself, I must skate. I cannot not skate.

It’s more natural for me on the ice. It’s terrible to say, but when I’m only living at home, when I’m only giving myself to

my parents and to Daria, I can feel my strength slipping away. When I skate, it returns. My confidence returns. This is good

for me, but it’s also good for Daria. She sees that her mom is not weak, that she can do something well. She likes the way

I skate, likes my costumes, likes the way I look on the ice. It’s the best way for me to express my emotions. It’s easier

than to write, than to talk, than to think. I just skate the elements that I’ve been skating all my life, and if I can perform

like I did the night of the tribute to Sergei, it’s perfect.

Some performances go better than others. On the tour now, when I skate alone, I don’t feel at all like I did when I skated

in Hartford for Sergei. Scott Hamilton told me that night, “Fill up the ice with yourself.” And I could. I felt huge, powerful,

double strong.

Now it’s like I never did that show. I don’t feel I have something so special to share with the audience. I imagine them saying,

“It’s too bad she’s skating alone.” Or maybe, “It’s nice to see her on the ice.” These thoughts are always going through my

head when I’m out there, which is distracting and disconcerting. I’m very aware that everyone’s just watching me. I don’t

know where my eyes should go. I never had this contact, mental and visual, with the audience when I skated before. I only

had contact with Sergei.

But I’m learning. I’ll figure it out. I know, someday in the future, I’ll coach. Not soon, I hope. But when I can’t skate

anymore. I have to tell someone the secrets I know about skating. It would be so great to help someone grow up to become a

champion. Sergei and I did a coaching clinic once in Canada, and he could see a mistake and explain exactly what to do about

it. All I did was translate for him. You have to have such patience to be a coach, and Sergei was definitely patient. You

have to watch a program, see a million mistakes, but not let your student see on your face that there’s a problem. Instead,

you must say, it was good, only maybe try this one thing. And the next day it’s another thing. And the next day another and

another. Patience.

I would never want Daria to grow up to be a skater. I shouldn’t write it like that. What I’d like is for her to have more

options than only being a skater. I want her to understand computers, to understand business, to understand politics. I’ll

see to it she has more education than I had, that she spends more time in school than I did. I want her to be beautiful in

the way my mother is beautiful—to be smart, strong, selfless, and have beautiful taste. I want her to be physically fit,

which is why I’d like to see her involved in some kind of sport when she’s young.

I want her to be whatever she wants to be. It’s what I admire in Daria already. She knows what she wants, and she doesn’t

care what her mom thinks about the matter. She was born like this. Maybe she inherited this from Sergei. If she wants to be

a skater, she’ll be a skater. And then I will do what I can to help.

I think I’ll be learning a lot of things from Daria in the future. I already am learning from her. Sergei never taught me

things. He protected me; he loved me; he took care of me; he comforted me. But it is only with his death that I start to learn

about life. Only now has he started to teach me.

I am learning that life doesn’t give everything to you. You also have to create your own future, your own opportunities. Before,

my life consisted of training, skating, winning, moving to the United States, and living with the person I loved. Everything

was too easy. The difficulties I encountered were trivial—not life-changing difficulties. They were things like the language

barrier, taking care of airplane tickets, breaking in new boots, training. These were nothing. I am learning that life is

more difficult than I thought.

Mostly, I’m learning about myself. It still hurts me to see couples that we knew. I ache inside when I see Nina and Viktor

Petrenko, to know that Nina can hug Viktor anytime she wants, that they can always hold each other’s hands. Nina’s such a

calm, reassuring presence, and sometimes I just want to lay my head on her shoulder, or someone’s shoulder. I never wished

to do this before with friends. With Sergei, I never thought about friends. I could see them, or not see them, for a long

time.