My Sergei (7 page)

Authors: Ekaterina Gordeeva,E. M. Swift

The best time for Zhuk was when we were training on the ice at Navagorsk, a center for elite athletes that was thirty minutes

from Moscow. Navagorsk was in the country, surrounded by forests. It had more than one hotel, each with its own cafeteria,

plus soccer fields, a movie theater, a swimming pool, a gym, a physical therapy center, and of course an ice rink. It wasn’t

just used by skaters. Athletes in soccer, volleyball, and basketball also trained there. We used to go to Navagorsk fifteen

days before every important competition: Nationals, Europeans, and Worlds.

For Zhuk it was ideal, because every night, instead of going home to our parents, we were in the hotel, and he could call

a meeting. He always found some business to do: either listening to music or going over the journals or talking about what

we were going to do the next day.

I was homesick all the time. I often cried myself to sleep at night. I shared a room with Anna Kondrashova, and Zhuk would

tease us about eating dinner at the cafeteria. Anna always had a problem keeping her weight down, so we stopped going to dinner

because afterward Zhuk would tell such stories about how much we ate and how much we’d weigh if we kept eating dinners like

that. Just the girls he’d tease. So instead we’d skip dinner and would walk fifteen minutes to town to buy fruits, vegetables,

and candy. Lots of candy. As I’m writing this, I can hardly believe what I’m saying. What were we thinking? How did we listen

to him?

One time I saw Zhuk hit Anna. I was in the bathroom, and Zhuk came and started talking loudly to her. I decided I’d better

stay where I was, but then they started fighting, and when I came out, he was hitting her on the back. I ran out to get Sergei,

but by the time we came back Zhuk was gone. Anna was crying. That was nothing new. She cried almost every day.

Zhuk used to come to her and say, “I saw you last night go into Fadeev’s room. What were you doing in there?” Even if she

had done this, it was none of his business, of course. But he would torment her with his spying, and I was so young that Anna

never confided in me what was behind it. I understand now that he was trying to get Anna to sleep with him. He had done this

with many girls over the years. Not me, fortunately, because I was so young. He had enough power that if a girl refused him,

he could arrange it so she couldn’t skate anymore. This was a man without a heart.

Maybe being around this man is what made me, not a strong person, in the way my mother is strong—but a tough person. Tough

enough to handle anything. Tough, not in a good way, but in a way that allows you to handle the bad things that life throws

at you. Tough but hard. Too hard sometimes.

The 1986 Nationals were held in Leningrad, and it was the first time Sergei and I had competed at the senior level. We skated

well, but to be honest I didn’t even worry about missing an element, because we were so perfectly trained. In my opinion we

were overtrained, with nothing else in our heads. We did side-by-side double axels, triple salchow throw, double axel throw,

triple twist. We finished second to the defending world champions, Elena Valova and Oleg Vassiliev. But Zhuk told us we had

skated better than them. “That’s okay,” he said. “You’ll be first at the Europeans.”

The Europeans were held in Copenhagen that year. Before we went, Zhuk made me go see an acupuncturist, who puts needles in

special places to make your pain go away. I don’t know where he found her, but her real magic was discovering the weakest

point in your body. She called it a hole. She found such a hole in me, right beneath my left shoulder blade. I had not known

this place was a problem until this woman told me it was, and pushed into this place until it hurt. She claimed she could

see through my whole body through this weak point. It was my most vulnerable spot. The funny thing was, it wasn’t like I had

a problem this lady was fixing. What kind of a problem do you have when you’re fourteen years old? The only problem I had

was I didn’t have enough time to play with my dolls. That was the problem. But this lady could see a weak spot on my back,

and she could touch it, and sure enough, because I had trained so much, it was a little bit painful. This was a very bad hole.

She gave me a special metallic disc to put over the hole, which she said would protect me. She attached it with a piece of

tape. Now I was prepared for the competition.

Then guess what? I lost it when I took a shower. And I thought, Oh no. That’s bad. I’ll fall down. I’ll miss all my elements

because of the exposed weak hole beneath my left shoulder blade. We were already in Copenhagen for the European Championships,

and I was distraught. Then right before the competition I found the metallic disc on the hotel room floor. So I put it back

on, and all was saved.

Zhuk told Sergei and Fadeev to come to see this lady, too, but they just laughed at him. He couldn’t force them. Sergei never

took any of it seriously. He was only serious with Zhuk during practice. And of course he was right. It wasn’t that he ever

caused a problem for Zhuk, or raised his voice, or told him off. He just knew that off the ice, his private life was his own.

He would do everything Zhuk said on the ice, but that was it. He was not obedient like me, who would do everything anyone

said.

Zhuk did, however, help me with my confidence. No one had expected us to be at the European Championships in 1986. They didn’t

even have our names listed in the program, which Zhuk took pains to point out to us. He told me, “You will skate clean.” But

I already knew that. And I was absolutely certain about Sergei. I never, ever worried about him. Even in practice I couldn’t

miss anything, because whenever we missed something during our practices, Zhuk made us do it over again. It was like my father

with the homework. Only instead of doing it once, we’d have to do it three times. I learned the double axel this way. Zhuk

would tell me to do five double axels in a row. And if I did four in a row and missed the fifth, I had to start over. Always

Zhuk had us practice a specific number of jumps.

We didn’t feel any pressure at the European Championships in Copenhagen, where we again finished second to Valova and Vassiliev.

But we skated our programs without a mistake. After the free program Elena Valova was crying so hard, because she knew we

skated better than she and Vassiliev, even though they won. She was having a lot of problems with her leg and wasn’t healthy

enough to skate her best.

The trip to Copenhagen seemed more like a holiday to me than a competition. The queen of Denmark came to the Sunday exhibition

and gave us huge boxes of Danish chocolate. We went shopping, and I remember buying some red boots that I later wore to the

World Championships in Geneva. Every day we got twenty dollars in living money, and I used it to buy jeans that actually fit

me, which were impossible to find in Moscow.

I could see clearly that life was nicer in every way in the West than it was at home. The streets were cleaner, the food was

better, the service was quicker and more friendly. It was totally different from what we were used to—it was a nicer life

but a more expensive life. I always brought gum and nice fruits home with me. During the winter it was impossible to get oranges

and apples in Moscow. I also bought souvenir T-shirts for Maria and pins for my grandfather.

As soon as we returned home, we had to start preparing for the Worlds. There was no chance to recharge. You’re so weak after

a competition from the travel and the emotional letdown that your body is susceptible to illness, and I came down with the

flu. Then Sergei and I had to keep doing our programs in practice, the same ones we’d skated so well at the Nationals and

the Europeans. Again and again and again, always under Zhuk’s critical eye.

So when we arrived in Geneva for the 1986 World Championships—our first—it wasn’t with the carefree spirit we’d had before

the Europeans. It was like going to work. I was more tired and nervous than I’d ever been before, and the whole competition

I could think of only one thing: I wanted to go home and be with my mom. I missed her so much.

Before the free program Zhuk told Sergei to take me for a walk, and we went to Lake Geneva to feed the swans. Sergei asked

me if I was nervous. I said I was. And he said, “Yeah, me too.” But he didn’t look nervous. He always looked so calm, and

to see him always made me feel calm, too. We didn’t talk much, and we didn’t touch each other. We still had an age barrier

between us.

We skated cleanly again, and when Valova and Vassiliev made some mistakes, for the first time all year we beat them. In our

first try, we had won the World Championships. I couldn’t believe it. I didn’t even like the program that Zhuk had created

for us. There was no theme, no choreography. The movements didn’t mean anything to me. The music was not classical, not jazzy

—it was almost like restaurant music, except there were funny, childish noises near the end of it, almost like a passing

train. What Zhuk had us doing with our hands had nothing to do with what we were doing with the rest of our bodies. We just

proceeded from element to element without feeling, intent only on not making mistakes.

I was, strange as it sounds, disappointed. It was our first trip to the World Championships, and we won. As we stood on the

winner’s stand, I remember thinking, Why are they giving me this medal? These are the World Championships, the ones you only

watch on TV. I never dreamed of being an Olympic or World Champion. And suddenly I was one, but somehow it didn’t feel right.

I went back to the hotel, sat down on my bed, and cried. It was too easy. It gave me no satisfaction. I cried and cried. Anna

Kondrashova looked at me and said, “What are you, crazy? You were great.” But I wasn’t happy about it.

Sergei went to the fountain in Lake Geneva the next day and wrote his name on it. He only told me about it years later, saying

in his teasing way, “Oh, you didn’t go with me? Too bad.”

That spring we performed with the other medalists on a twenty-city tour sponsored by the International Skating Union (ISU),

through Switzerland, France, and Germany. We traveled by bus, and despite the fact that it was our first such tour, looking

out the window was the only fun thing about it, thanks to Zhuk. I passed the time doing needlepoint. It was very boring, and

the skating was difficult. Zhuk made us do either our short or long program every night, because we had no exhibition numbers

—the fun, often frivolous programs that skaters prepare in case they’re asked to perform in a show. They’re never as difficult

as competition programs. But Zhuk made us do all our throws and jumps. The buildings where we skated, in places like Davos,

were cold, and we never had a chance to properly warm up.

Zhuk roomed with Sergei, and he would follow Sergei around, spying on him, never letting him go anywhere by himself. Zhuk

gave trouble to all the Soviet skaters, refusing to let us go to the discos with the others. He told us that if we did, we’d

never be Olympic champions. The worst thing was, I was so disciplined that even if someone had asked me to come along, I wouldn’t

have gone.

Brian Boitano, who was also on this tour, later told me that he and Alexander Fadeev, whom everyone called Sasha, went for

a walk one day, and Sergei came along. Brian asked Sasha, who spoke English, to ask Sergei what he loved about skating. Sergei

said that he didn’t love skating. He skated because he had to.

That feeling in him eventually changed. But at the time I suppose it was true. It was so depressing to have to listen to Zhuk

every day. He put pressure on us the whole season: from Nationals to Europeans to Worlds to the tour. It’s why I don’t like

the memory of our first World Championships.

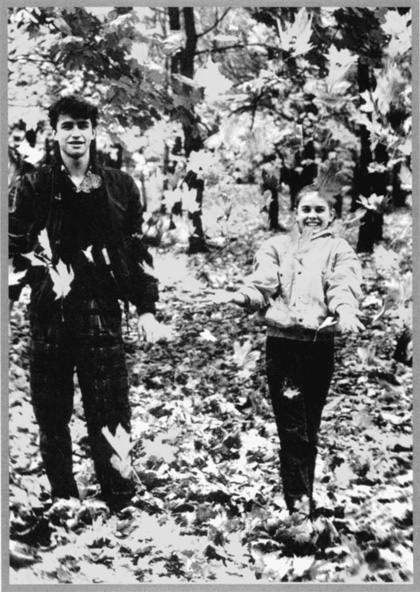

Strolling in a Moscow park in fall 1986, shortly after our first World Championships.

S

ometime during the summer of 1986, Sergei, Alexander

Fadeev, Anna Kondrashova, and Marina Zueva prepared a letter to send to Central Red Army Club officials asking that Zhuk

be removed as head coach. He had become intolerable, drinking for days on end, missing practices, and becoming increasingly

abusive to the boys. He wasn’t fit to be coaching anyone, old or young. They asked me to sign it too, which I did.

My father was angry. He said to me, “This wasn’t your idea. Why can’t you think for yourself? Make up your own mind rather

than allow yourself to be influenced by the others.” He was right about one thing. I am a Gemini. I tend to look at something

one way one day, then the opposite way the next. I am too influenced by the opinions of others. But not in the matter of Zhuk.

I despised this man every day. My father, however, thought that Zhuk was a great coach, figure skating’s equivalent to the

legendary father of Russian hockey, Anatoly Tarasov. If he had a problem with drinking, he believed it could be solved.

Sergei, however, had made his decision. He talked to my father several times that summer, just a few words, but he told him

he had to change coaches. Under no conditions was he going to train with Zhuk anymore. I remember overhearing them on the

street one day, talking very seriously, and Sergei telling my father, “She’s going to skate with me, and I’m going to decide

what coach we’ll have.” Sergei never told me, “Don’t worry, I’ll take care of you,” but I always felt it was so.