My Stroke of Insight: A Brain Scientist's Personal Journey (6 page)

Read My Stroke of Insight: A Brain Scientist's Personal Journey Online

Authors: Jill Bolte Taylor

Tags: #Heart, #Cerebrovascular Disease, #Diseases, #Health & Fitness, #Body; Mind & Spirit, #Medical, #Biography, #Cerebrovascular Disease - Patients - United States, #Rehabilitation, #United States, #Brain, #Patients, #Personal Memoirs, #Taylor; Jill Bolte - Health, #Biography & Autobiography, #Neuroscience, #Cerebrovascular Disease - Patients - Rehabilitation, #Science & Technology, #Nervous System (Incl. Brain), #Healing

Following surgery, it took eight years for me to completely recover all physical and mental functions. I believe I have recovered completely because I had an advantage. As a trained neuroanatomist, I believed in the plasticity of my brain - its ability to repair, replace, and retrain its neural circuitry. In addition, thanks to my academics, I had a "roadmap" to understanding how my brain cells needed to be treated in order for them to recover.

The story that follows is my stroke of insight into the beauty and resiliency of the human brain. It's a personal account, as seen through the eyes of a neuroscientist, about what it felt like to experience the deterioration of my left brain and then recover it. It is my hope that this book will offer insight into how the brain works in both wellness and in illness. Although this book is written for the general public, I hope you will share it with people you want to help recover from brain trauma and their caregivers.

Roger W. Sperry's December 8, 1981 lecture (Accessed on September 10, 2006), <

http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1981/sperry-lecture.html

>

Sperry, M.S. Gazzaniga, and J.E. Bogen, "Interhemispheric Relationships: The Neurocortical Commissures; Syndromes of Hemisphere Disconnection" in

Handbook of Clinical Neurology

, P.J. Vinken and G.W. Bruyn, eds. (Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing, 1969), 177-184.

Andrew Newberg, Eugene D'Aquili, and Vince Rause,

Why God Won't Go Away

(NY: Ballantine, 2001), 28.

It was 7:00 am on December 10, 1996. I awoke to the familiar tick-tick-tick of my compact disc player as it began winding up to play. Sleepily, I hit the snooze button just in time to catch the next mental wave back into dreamland. Here, in this magic land I call "Thetaville" - a surreal place of altered consciousness somewhere between dreams and stark reality - my spirit beamed beautiful, fluid, and free from the confines of normal reality.

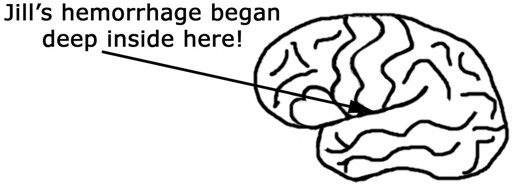

Six minutes later, as the tick-tick-tick of the CD alerted my memory that I was a land mammal, I sluggishly awoke to a sharp pain piercing my brain directly behind my left eye. Squinting into the early morning light, I clicked off the impending alarm with my right hand and instinctively pressed the palm of my left hand firmly against the side of my face. Rarely ill, I thought how queer it was for me to awaken to such a striking pain. As my left eye pulsed with a slow and deliberate rhythm, I felt bewildered and irritated. The throbbing pain behind my eye was sharp, like the caustic sensation that sometimes accompanies biting into ice cream.

As I rolled out of my warm waterbed, I stumbled into the world with the ambivalence of a wounded soldier. I closed the bedroom window blind to block the incoming stream of light from stinging my eyes. I decided that exercise might get my blood flowing and perhaps help dissipate the pain. Within moments, I hopped on to my "cardio-glider" (a full body exercise machine) and began jamming away to Shania Twain singing the lyrics, "Whose bed have your boots been under?". Immediately, I felt a powerful and unusual sense of dissociation roll over me. I felt so peculiar that I questioned my well-being. Even though my thoughts seemed lucid, my body felt irregular. As I watched my hands and arms rocking forward and back, forward and back, in opposing synchrony with my torso, I felt strangely detached from my normal cognitive functions. It was as if the integrity of my mind/body connection had somehow become compromised.

Feeling detached from normal reality, I seemed to be witnessing my activity as opposed to feeling like the active participant performing the action. I felt as though I was observing myself in motion, as in the playback of a memory. My fingers, as they grasped onto the handrail, looked like primitive claws. For a few seconds I rocked and watched, with riveting wonder, as my body oscillated rhythmically and mechanically. My torso moved up and down in perfect cadence with the music and my head continued to ache.

I felt bizarre, as if my conscious mind was suspended somewhere between my normal reality and some esoteric space. Although this experience was somewhat reminiscent of my morning time in Thetaville, I was sure that this time I was awake. Yet, I felt as if I was trapped inside the perception of a meditation that I could neither stop nor

Morning of the Stroke

escape. Feeling dazed, the frequency of shooting pangs escalated inside my brain, and I realized that this exercise regime was probably not a good idea.

39

Feeling a little nervous about my physical condition, I climbed off the machine and bumbled through my living room on the way to the bath. As I walked, I noticed that my movements were no longer fluid. Instead they felt deliberate and almost jerky. In the absence of my normal muscular coordination, there was no grace to my pace and my balance was so impaired that my mind seemed completely preoccupied with just keeping me upright.

As I lifted my leg to step into the tub, I held on to the wall for support. It seemed odd that I could sense the inner activities of my brain as it adjusted and readjusted all of the opposing muscle groups in my lower extremities to prevent me from falling over. My perception of these automatic body responses was no longer an exercise in intellectual conceptualization. Instead, I was momentarily privy to a precise and experiential understanding of how hard the fifty trillion cells in my brain and body were working in perfect unison to maintain the flexibility and integrity of my physical form. Through the eyes of an avid enthusiast of the magnificence of the human design, I witnessed with awe the autonomic functioning of my nervous system as it calculated and recalculated every joint angle.

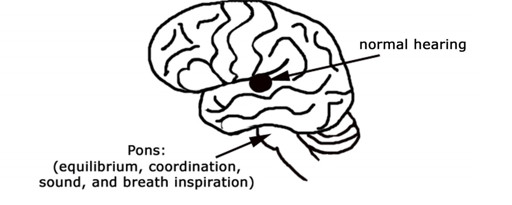

Ignorant to the degree of danger my body was in, I balanced my weight against the shower wall. As I leaned forward to turn on the faucet, I was startled by an abrupt and exaggerated clamor as water surged into the tub. This unexpected amplification of sound was both enlightening and disturbing. It brought me to the realization that, in addition to having problems with coordination and equilibrium, my ability to process incoming sound (auditory information) was erratic.

I understood neuroanatomically that coordination, equilibrium, audition and the action of inspirational

breathing were processed through the pons of my brainstem. For the first time, I considered the possibility that I was perhaps having a major neurological malfunction that was life threatening.

Fibers Passing Through the Pons of the Brainstem

As my cognitive mind searched for an explanation about what was happening anatomically inside my brain, I reeled backward in response to the augmented roar of the water as the unexpected noise pierced my delicate and aching brain. In that instant, I suddenly felt vulnerable, and I noticed that the constant brain chatter that routinely familiarized me with my surroundings was no longer a predictable and constant flow of conversation. Instead, my verbal thoughts were now inconsistent, fragmented, and interrupted by an intermittent silence.

Morning of the Stroke

When I realized that the sensations outside of me, including the remote sounds of a bustling city beyond my apartment window, had faded away, I could tell that the broad range of my natural observation had become constricted. As my brain chatter began to disintegrate, I felt an odd sense of isolation. My blood pressure must have been dropping as a result of the bleeding in my brain because I felt as if all of my systems, including my mind's ability to instigate movement, were moving into a slow mode of operation. Yet, even though my thoughts were no longer a constant stream of chatter about the external world and my relationship to it, I was conscious and constantly present within my mind.

41

Confused, I searched the memory banks of both my body and brain, questioning and analyzing anything I could remember having experienced in the past that was remotely similar to this situation.

What is going on?

I wondered.

Have I ever experienced anything like this before? Have I ever felt like this before? This feels like a migraine. What is happening in my brain?

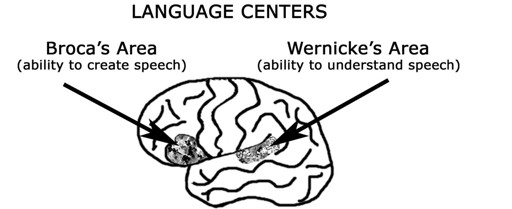

The harder I tried to concentrate, the more fleeting my ideas seemed to be. Instead of finding answers and information, I met a growing sense of peace. In place of that constant chatter that had attached me to the details of my life, I felt enfolded by a blanket of tranquil euphoria. How fortunate I was that the portion of my brain that registered fear, my amygdala, had not reacted with alarm to these unusual circumstances and shifted me into a state of panic. As the language centers in my left hemisphere grew increasingly silent and I became detached from the memories of my life, I was comforted by an expanding sense of grace. In this void of higher cognition and details pertaining to my normal life, my consciousness soared into an all-knowingness, a "being at

one

" with the universe, if you will. In a compelling sort of way, it felt like the good road home and I liked it.

By this point I had lost touch with much of the

physical three-dimensional reality that surrounded me. My body was propped up against the shower wall and I found it odd that I was aware that I could no longer clearly discern the physical boundaries of where I began and where I ended. I sensed the composition of my being as that of a fluid rather than that of a solid. I no longer perceived myself as a whole object separate from everything. Instead, I now blended in with the space and flow around me. Beholding a growing sense of detachment between my cognitive mind and my ability to control and finely manipulate my fingers, the mass of my body felt heavy and my energy waned.