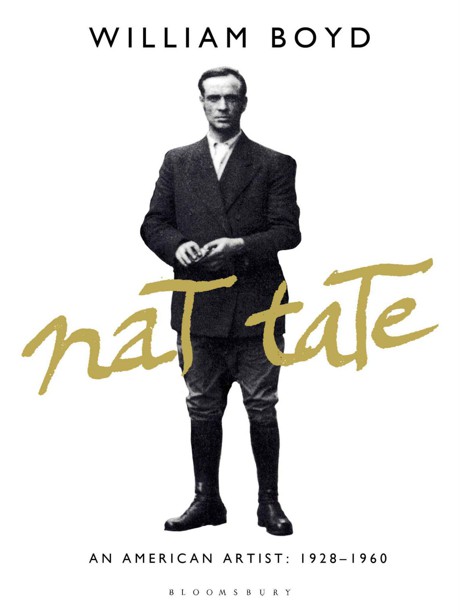

Nat Tate: An American Artist: 1928-1960

Read Nat Tate: An American Artist: 1928-1960 Online

Authors: William Boyd

For Susan

Contents

I still don’t know what made me climb the stairs to Alice Singer’s 57th Street gallery. It was June 1997, New York City. The show was titled, ‘Crowding the Air – American Drawing 1900–1990’, and it seemed impossibly ambitious for her smallish space. Furthermore, the notices of it which I had read in the

Times

and the

New Yorker

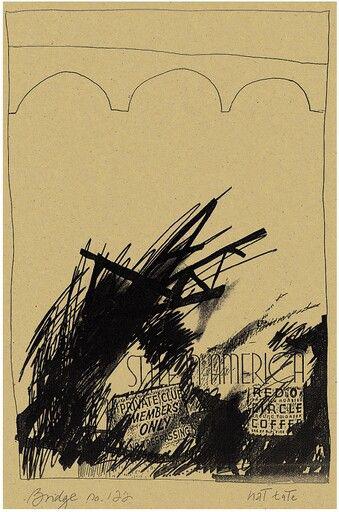

disdainfully prefigured one’s natural prejudices. It was late afternoon, I was hot and I was tired and I wandered past dozens of unremarkable drawings and sketches – a Feininger, a Warhol shoe, a Twombly doodle caught my eye – before I was held and shocked by something I had never expected to see. It was a drawing, 12" × 8", in ink, mixed media and collage:

Bridge no. 122

. I did not need to read the printed label beside it to know it was by Nat Tate.

It was undated, but I knew it must have been executed in the early 1950s, part of his once legendary, now almost entirely forgotten series of drawings inspired by Hart Crane’s great poem,

The Bridge

. All the drawings in this series – and it was reputed to run eventually to over 200 – were of similar format: at the top was the boldly stylised representation of a bridge, sometimes a tangle of girders, sometimes a simple arc, and on the bottom two thirds or half of the page was accumulated a sort of clutter or litter – slashing ink strokes, or furious cross-hatching, occasional half-representational figures, sometimes obscenely graffito-like, sometimes finely and carefully drawn, or lettering, or pasted letters, illustrations torn from magazines, skilfully juxtaposed collages in a style reminiscent of Kurt Schwitters. ‘I like bridges,’ Nat Tate once told an acquaintance, ‘so strong, so simple – but imagine what flows in the river underneath.’

Nat Tate,

Bridge no. 122

The acquaintance to whom these words had been confided was the British writer and critic Logan Mountstuart (1906–1991 – whose journals I am currently editing

1

). Mountstuart is a curious and forgotten figure in the annals of twentieth-century literary life. ‘A man of letters’ is probably the only description which does justice to his strange career – by turns acclaimed or wholly indigent. Biographer, belle-lettriste, editor, failed novelist, he was perhaps most successful at happening to be in the right place at the right time during most of the century, and his journal – a huge, copious document – will probably prove his lasting memorial. Mountstuart lived in New York from 1947–71 and his extensive journals provide a remarkably candid and intimate portrait of the Manhattan artistic and literary circles in which he moved. Indeed even my own patchy and conflicting account of Nat Tate’s life and times – full of ambiguities and contention – could not have been compiled without the Mountstuart journals and the letters between Mountstuart and Janet Felzer

2

, the dealer who first showed Tate’s work in her lower Manhattan ‘co-op’ gallery in 1952.

Mountstuart met Nat Tate in that year and saw him from time to time thereafter. Although he could not be described as a close friend, Mountstuart was also a patron – he owned several Tate drawings, three from the

Bridge

sequence, and at least two of the larger, later paintings – and was a regular visitor to Tate’s studio on 22nd Street and Lexington Avenue, a rare honour. Tate, by nature a diffident and awkward personality, seemed curiously at ease with Mountstuart (at least by Mountstuart’s account). Mountstuart himself thought this was because he was British – and therefore ‘foreign’ – and also because he knew Europe and European artists. Nat Tate visited Europe only once in his short life, a trip he had both dreaded and longed for.

Nathwell – ‘Nat’ – Tate was born on the 7th March 1928, probably in Union Beach, New Jersey. His mother, Mary (née Tager), told him his father had been a fisherman from Nantucket who had drowned at sea before Nat had been born. The regular contradictions and elaborations of Mary Tate’s story (Nathwell senior was variously a submariner, a naval architect, a merchant seaman killed ‘in a war’, a deep sea diver) later convinced his son that he was in fact illegitimate. However, there was in all the versions a link with the sea and, with ominous symbolism, the death was always the same – drowning. The only relative Mary Tate appeared to have was an aunt in Union Beach, whom Nat recalled visiting a few times. In his darker moments he fantasised that his mother had been a dockside whore and that he was the product of a swift and carnal midnight coupling with a sailor. Hence, he argued, the consistency of the identities she bestowed on his father. Whether this man was still alive, or who he actually was, Nat would clearly never know. He decided that his mother had had, in her imagination, his father ‘drowned’ as a punishment and as a mark of her own shame. It is plausible, though perhaps a little fanciful, to find some psychological sources here for the

Bridge

drawings: to see the bridges – simple, clear, strong – as a way of traversing safely the dark and turbulent water below, to walk, unsmirched and untouched, over the rebarbative flotsam and jetsam on the river bed beneath.

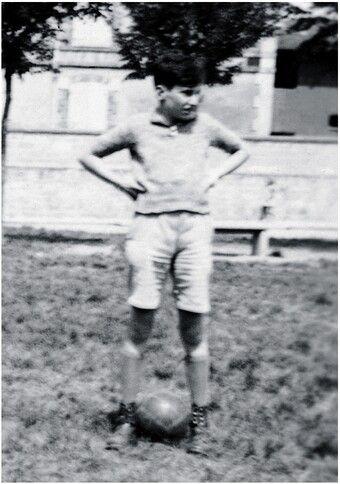

Nat Tate, aged nine, in the gardens of Windrose, 1937

Whatever the identity of the mysterious Nathwell Tate senior, Mary Tager took his name, referred to herself as Mrs Nathwell Tate, and pointedly described herself to anyone who asked as a widow. She remains a shadowy figure: ‘I remember my mother was a great polisher of glasses,’ Tate once recalled to Mountstuart, ‘perhaps she once worked in a bar . . .’. In any event she was a good housekeeper and she moved with her little boy to Peconic, Long Island, where she found work with Peter and Irina Barkasian as a kitchen maid, later being promoted to cook. Nat Tate was three years old, it was 1931, Peconic was his first real home; he had no memories of any life before Peconic and he had no idea where Mary Tate had moved from.

Peter Barkasian was a wealthy man: his father Dusan Barkasian had built up a logging and timber business into the conglomerate known as Albany Paper Mills. On his father’s death in 1927, Peter immediately, and presciently, sold Albany Paper to Du Pont Chemicals and retired (aged 36) to live comfortably on the proceeds. The 1929 crash left him unscathed and his finances intact.