Natasha's Dance (25 page)

In 1859 Tolstoy started a school for peasant children at Yasnaya Polyana, the old Volkonsky estate that had passed down to him on his mother’s side. The estate had a special meaning for Tolstoy. He had been born in the manor house - on a dark green leather sofa which he kept throughout his life in the study where he wrote his great novels. He spent his childhood on the estate, until the age of nine, when he moved to Moscow with his father. More than an estate, Yasnaya Polyana was his ancestral nest, the place where his childhood memories were kept, and the little patch of Russia where he felt he most belonged. ‘I wouldn’t sell the house for anything,’ Tolstoy told his brother in 1852. ‘It’s the last thing I’d be prepared to part with.’

171

Yasnaya Polyana had been purchased by Tolstoy’s great-grandmother, Maria Volkonsky, in 1763. His grandfather, Nikolai Volkonsky, had developed it as a cultural space, building the splendid manor house, with its large collection of European books, the landscaped park and lakes, the spinning factory, and the famous white stone entrance gates that served as a post station on the road from Tula to Moscow. As a boy, Tolstoy idolized his grandfather. He fantasized that he was just like him.

172

This ancestor cult, which was at the emotional core of Tolstoy’s conservatism, was expressed in Eugene, the hero of his story ‘The Devil’ (1889):

171

Yasnaya Polyana had been purchased by Tolstoy’s great-grandmother, Maria Volkonsky, in 1763. His grandfather, Nikolai Volkonsky, had developed it as a cultural space, building the splendid manor house, with its large collection of European books, the landscaped park and lakes, the spinning factory, and the famous white stone entrance gates that served as a post station on the road from Tula to Moscow. As a boy, Tolstoy idolized his grandfather. He fantasized that he was just like him.

172

This ancestor cult, which was at the emotional core of Tolstoy’s conservatism, was expressed in Eugene, the hero of his story ‘The Devil’ (1889):

It is generally supposed that Conservatives are old people, and that those in favour of change are the young. That is not quite correct. Usually Conservatives are young people: those who want to live but who do not think about how to live, and have not time to think, and therefore take as a model for themselves a way of life that they have seen. Thus it was with Eugene. Having settled in the village, his aim and ideal was to restore the form of life that had existed, not in his father’s time… but in his grandfather’s.

173

173

Nikolai Volkonsky was brought back to life as Andrei’s father Nikolai Bolkonsky in

War and Peace

- the retired general, proud and independent, who spends his final years on the estate at Bald Hill, dedicating himself to the education of his daughter called (like Tolstoy’s mother) Maria.

War and Peace

- the retired general, proud and independent, who spends his final years on the estate at Bald Hill, dedicating himself to the education of his daughter called (like Tolstoy’s mother) Maria.

War and Peace

was originally conceived as a ‘Decembrist novel’, loosely based on the life story of Sergei Volkonsky. But the more the

was originally conceived as a ‘Decembrist novel’, loosely based on the life story of Sergei Volkonsky. But the more the

writer researched into the Decembrists, the more he realized that their intellectual roots lay in the war of 1812. In the novel’s early form

(The Decembrist)

the Decembrist hero returns after thirty years of exile in Siberia to the intellectual ferment of the late 1850s. A second Alexandrine reign has just begun, with the accession of Alexander II to the throne in 1855, and once again, as in 1825, high hopes for political reform are in the air. It was with such hopes that Volkonsky returned to Russia in 1856 and wrote about a new life based on truth:

(The Decembrist)

the Decembrist hero returns after thirty years of exile in Siberia to the intellectual ferment of the late 1850s. A second Alexandrine reign has just begun, with the accession of Alexander II to the throne in 1855, and once again, as in 1825, high hopes for political reform are in the air. It was with such hopes that Volkonsky returned to Russia in 1856 and wrote about a new life based on truth:

Falsehood. This is the sickness of the Russian state. Falsehood and its sisters, hypocrisy and cynicism. Russia could not exist without them. Yet surely the point is not just to exist but to exist with dignity. And if we want to be honest with ourselves, then we must recognize that if Russia cannot exist otherwise than she existed in the past, then she does not deserve to exist.

174

174

To live in truth, or, more importantly, to live in truth in Russia - these were the questions of Tolstoy’s life and work, and the main concerns of

War and Peace.

They were first articulated by the men of 1812.

War and Peace.

They were first articulated by the men of 1812.

Volkonsky’s release from exile was one of the first acts of the new Tsar. Of the 121 Decembrists who had been sent into exile in 1826, only nineteen lived to return to Russia in 1856. Sergei himself was a broken man, and his health never really recovered from the hardships of Siberia. Forbidden to settle in the two main cities, he was none the less a frequent guest in the Moscow houses of the Slavophiles, who saw his gentle nature, his patient suffering, his simple ‘peasant’ lifestyle and his closeness to the land as quintessential ‘Russian’ qualities.

175

Moscow’s students idolized Volkonsky. With his long white beard and hair, his sad, expressive face, ‘pale and tender like the moon’, he was regarded as a ‘sort of Christ who had emerged from the Russian wilderness’.

176

A symbol of the democratic cause that had been interrupted by the oppressive regime of Nicholas I, Volkonsky was a living connection between the Decembrists and the Populists, who emerged as the people’s champions in the 1860s and 1870s. Volkonsky himself remained true to the ideals of 1812. He continued to reject the values of the bureaucratic state and the aristocracy and, in the spirit of the Decembrists, he continued to uphold the civic obligation to live an honest life in the service of the people, who embodied the nation. ‘You

175

Moscow’s students idolized Volkonsky. With his long white beard and hair, his sad, expressive face, ‘pale and tender like the moon’, he was regarded as a ‘sort of Christ who had emerged from the Russian wilderness’.

176

A symbol of the democratic cause that had been interrupted by the oppressive regime of Nicholas I, Volkonsky was a living connection between the Decembrists and the Populists, who emerged as the people’s champions in the 1860s and 1870s. Volkonsky himself remained true to the ideals of 1812. He continued to reject the values of the bureaucratic state and the aristocracy and, in the spirit of the Decembrists, he continued to uphold the civic obligation to live an honest life in the service of the people, who embodied the nation. ‘You

9.

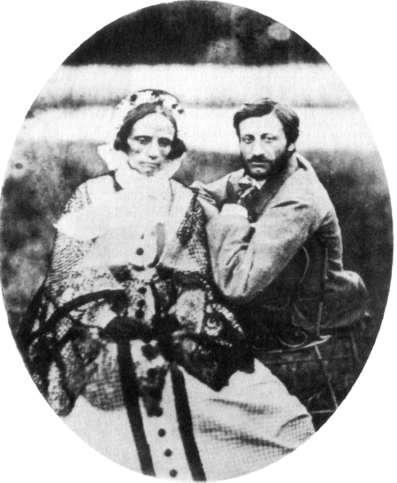

Maria Volkonsky and her son Misha. Daguerreotype, 1862. Maria was suffering from a kidney disease and died a year later

Maria Volkonsky and her son Misha. Daguerreotype, 1862. Maria was suffering from a kidney disease and died a year later

know from experience,’ he wrote to his son Misha (now serving in the army in the Amur region) in 1857,

that I have never tried to persuade you of my own political convictions -they belong to me. In your mother’s scheme you were directed towards the governmental sphere, and I gave my blessing when you went into the service of the Fatherland and Tsar. But I always taught you to conduct yourself

without lordly airs when dealing with your comrades from a different class. You made your own way - without the patronage of your grandmother - and knowing that, my friend, will give me peace until the day when I go to my grave.

177

177

Volkonsky’s notion of the Fatherland was intimately linked with his idea of the Tsar: he saw the sovereign as a symbol of Russia. Throughout his life he remained a monarchist - so much so indeed that when he heard about the death of Nicholas I, the Tsar who had sent him into exile thirty years before, Volkonsky broke down and cried like a child. ‘Your father weeps all day’, Maria wrote to Misha, ‘it is already the third day and I don’t know what to do with him.’

178

Perhaps Volkonsky was grieving for the man he had known as a boy. Or perhaps his death was a catharsis of the suffering he had endured in Siberia. But Volkonsky’s tears were tears for Russia, too: he saw the Tsar as the Empire’s single unifying force and was afraid for his country now that the Tsar was dead.

178

Perhaps Volkonsky was grieving for the man he had known as a boy. Or perhaps his death was a catharsis of the suffering he had endured in Siberia. But Volkonsky’s tears were tears for Russia, too: he saw the Tsar as the Empire’s single unifying force and was afraid for his country now that the Tsar was dead.

Volkonsky’s trust in the Russian monarchy was not returned. The former exile was kept under almost constant police surveillance on the orders of the Tsar after his return from Siberia. He was refused the restoration of his princely title and his property. But what hurt him most was the government’s refusal to return his medals from the war of 1812.* Thirty years of exile had not changed his love for Russia. He followed the Crimean War between 1853 and 1856 with obsessive interest and was deeply stirred by the heroism of the defenders at Sevastopol (among them the young Tolstoy). The old soldier (at the age of sixty-four) had even petitioned to join them as a humble private in the infantry, and it was only his wife’s pleading that eventually

* Eventually, after several years of petitioning, the Tsar returned them in 1864. But other forms of recognition took longer. In 1822 the English artist George Dawe was commissioned to paint Volkonsky’s portrait for the ‘Gallery of Heroes’ - 332: portraits of the military leaders of 1812. - in the Winter Palace in St Petersburg. After the Decembrist uprising Volkonsky’s portrait was removed, leaving a black square in the line-up of portraits. In 1903 Volkonsky’s nephew, Ivan Vsevolozhsky, Director of the Hermitage, petitioned Tsar Nicholas II to restore the picture to its rightful place. ‘Yes, of course,’ replied the Tsar, ‘it was so long ago’ (S. M. Volkonskii, O

dekabristakh: po semeinum vospominaniiam

(Moscow, 1994), p. 87).

dekabristakh: po semeinum vospominaniiam

(Moscow, 1994), p. 87).

dissuaded him. He saw the war as a return to the spirit of 1812, and he was convinced that Russia would again be victorious against the French.

179

179

It was not. Yet Russia’s defeat made more likely Volkonsky’s second hope: the emancipation of the serfs. The new Tsar, Alexander II, was another child of 1812. He had been educated by the liberal poet Vasily Zhukovsky, who had been appointed tutor to the court in 1817. In 1822 Zhukovsky had set free the serfs on his estate. His humanism had a major influence on the future Tsar. The defeat in the Crimean War had persuaded Alexander that Russia could not compete with the Western powers until it swept aside its old serf economy and modernized itself. The gentry had very little idea how to make a profit from their estates. Most of them knew next to nothing about agriculture or accounting. Yet they went on spending in the same old lavish way as they had always done, mounting up enormous debts. By 1859, one-third of the estates and two-thirds of the serfs owned by the landed nobles had been mortgaged to the state and noble banks. Many of the smaller landowners could barely afford to feed their serfs. The economic argument for emancipation was becoming irrefutable, and many landowners were shifting willy-nilly to the free labour system by contracting other people’s serfs. Since the peasantry’s redemption payments would cancel out the gentry’s debts, the economic rationale was becoming equally irresistible.*

But there was more than money to the arguments. The Tsar believed that the emancipation was a necessary measure to prevent a revolution from below. The soldiers who had fought in the Crimean War had been led to expect their freedom, and in the first six years of Alexander’s reign, before the emancipation was decreed, there were 500 peasant uprisings against the gentry on the land.

180

Like Volkonsky, Alexander was convinced that emancipation was, in Volkonsky’s words, a ‘ques-

180

Like Volkonsky, Alexander was convinced that emancipation was, in Volkonsky’s words, a ‘ques-

* Under the terms of emancipation the peasants were obliged to pay redemption dues on the communal lands which were transferred to them. These repayments, calculated by the gentry’s own land commissions, were to be repaid over a 49-year period to the state, which recompensed the gentry in 1861. Thus, in effect, the serfs bought their freedom by paying off their masters’ debts. The redemption payments became increasingly difficult to collect, not least because the peasantry regarded them as unjust from the start. They were finally cancelled in 1905.

tion of justice… a moral and a Christian obligation, for every citizen who loves his Fatherland’.

181

As the Decembrist explained in a letter to Pushchin, the abolition of serfdom was ‘the least the state could do to recognize the sacrifice the peasantry has made in the last two wars: it is time to recognize that the Russian peasant is a citizen as well’.

182

181

As the Decembrist explained in a letter to Pushchin, the abolition of serfdom was ‘the least the state could do to recognize the sacrifice the peasantry has made in the last two wars: it is time to recognize that the Russian peasant is a citizen as well’.

182

In 1858 the Tsar appointed a special commission to formulate proposals for the emancipation in consultation with provincial gentry committees. Under pressure from the diehard squires to limit the reform or to fix the rules for the land transfers in their favour, the commission became bogged down in political wrangling for the best part of two years. Having waited all his life for this moment, Volkonsky was afraid that he ‘might die before emancipation came to pass’.

183

The old prince was sceptical of the landed gentry, knowing their resistance to the spirit of reform and fearing their ability to obstruct the emancipation or use it to increase their exploitation of the peasantry. Although not invited on to any commission, Volkonsky sketched out his own progressive plans for the emancipation, in which he envisaged a state bank to advance loans to individual peasants to buy small plots of the gentry’s land as private property. The peasants would repay these loans by working their allotments of communal land.

184

Volkonsky’s programme was not dissimilar to the land reforms of Pyotr Stolypin, the Prime Minister and last reformist hope of Tsarist Russia between 1906 and 1911. Had such a programme been implemented in 1861, Russia might have become a more prosperous place.

183

The old prince was sceptical of the landed gentry, knowing their resistance to the spirit of reform and fearing their ability to obstruct the emancipation or use it to increase their exploitation of the peasantry. Although not invited on to any commission, Volkonsky sketched out his own progressive plans for the emancipation, in which he envisaged a state bank to advance loans to individual peasants to buy small plots of the gentry’s land as private property. The peasants would repay these loans by working their allotments of communal land.

184

Volkonsky’s programme was not dissimilar to the land reforms of Pyotr Stolypin, the Prime Minister and last reformist hope of Tsarist Russia between 1906 and 1911. Had such a programme been implemented in 1861, Russia might have become a more prosperous place.

In the end the diehard gentry was defeated and the moderate reformists got their way, thanks in no small measure to the personal intervention of the Tsar. The Law of the Emancipation was signed by Alexander on 19 February 1861. It was not as far-reaching as the peasantry had hoped, and there were rebellions in many areas. The Law allowed landowners considerable leeway in choosing the bits of land for transfer to the peasantry - and in setting the price for them. Overall, perhaps half the farming land in European Russia was transferred from the gentry’s ownership to the communal tenure of the peasantry, although the precise proportion depended largely on the landowner’s will. Owing to the growth of the population it was still far from enough to liberate the peasantry from poverty. Even on the old estates of Sergei Volkonsky, where the prince’s influence ensured

that nearly all the land was transferred to the peasants, there remained a shortage of agricultural land, and by the middle of the 1870s there were angry demonstrations by the peasantry.

185

None the less, despite its disappointment for the peasantry, the emancipation was a crucial watershed. Freedom of a sort, however limited it may have been in practice, had at last been granted to the mass of the people, and there were grounds to hope for a national rebirth, and reconciliation between the landowners and the peasantry. The liberal spirit of 1812 had triumphed in the end - or so it seemed.

185

None the less, despite its disappointment for the peasantry, the emancipation was a crucial watershed. Freedom of a sort, however limited it may have been in practice, had at last been granted to the mass of the people, and there were grounds to hope for a national rebirth, and reconciliation between the landowners and the peasantry. The liberal spirit of 1812 had triumphed in the end - or so it seemed.

Other books

Apache Dawn: Book I of the Wildfire Saga by Marcus Richardson

En Grand Central Station me senté y lloré by Elisabeth Smart

Time Past by Maxine McArthur

Everwild (The Healer Series, #1) by Kayla Jo

Sarah My Beloved (Little Hickman Creek Series #2) by Sharlene Maclaren

Naughty Nanny Series-Free Loving by Azod, Shara

The Veredor Chronicles: Book 03 - The Gate and Beyond by E J Gilmour

Going Deep (Divemasters Book 2) by Jayne Rylon

Siren's Secret by Trish Albright

Analog SFF, March 2012 by Dell Magazine Authors