Natasha's Dance (60 page)

people believed in a forest monster called ‘

Vorsa’.

They had a ‘living soul’ they called an

‘ort’,

which shadowed people through their lives and appeared before them at the moment of their death. They prayed to the spirits of the water and the wind; they spoke to the fire as if they were speaking to a living thing; and their folk art still showed signs of worshipping the sun. Some of the Komi people told Kandinsky that the stars were nailed on to the sky.

4

Vorsa’.

They had a ‘living soul’ they called an

‘ort’,

which shadowed people through their lives and appeared before them at the moment of their death. They prayed to the spirits of the water and the wind; they spoke to the fire as if they were speaking to a living thing; and their folk art still showed signs of worshipping the sun. Some of the Komi people told Kandinsky that the stars were nailed on to the sky.

4

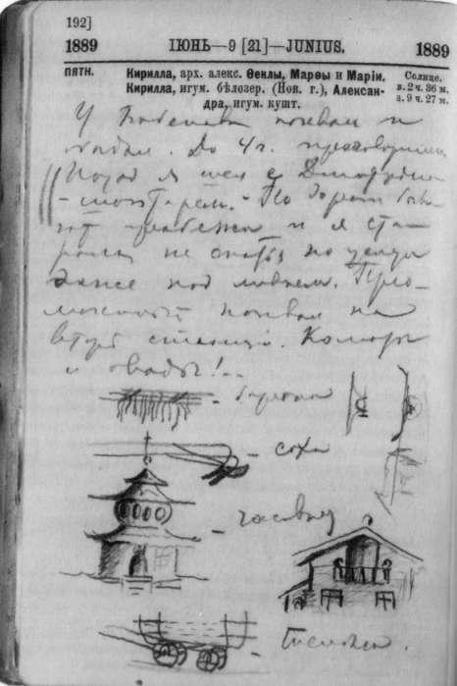

Scratching the surface of Komi life Kandinsky had revealed its Asian origins. For centuries the Finno-Ugric tribes had intermingled with the Turkic peoples of northern Asia and the Central Asian steppe. Nineteenth-century archaeologists in the Komi region had unearthed large amounts of ceramic pottery with Mongolian ornament. Kandinsky found a chapel with a Mongolian roof, which he sketched in his journal of the trip.

5

Nineteenth-century philologists subscribed to the theory of a Ural-Altaic family of languages that united the Finns with the Ostiaks, the Voguls, Samoyeds and Mongols in a single culture stretching from Finland to Manchuria. The idea was advanced in the 1850s by the Finnish explorer M. A. Castren, whose journeys to the east of the Urals had uncovered many things he recognized from home.

6

Castren’s observations were borne out by later scholarship. There are shamanistic motifs, for example, in the

Kalevala,

or ‘Land of Heroes’, the Finnish national epic poem, which may suggest a historical connection to the peoples of the East, although the Finns themselves regard their poem as a Baltic Odyssey in the purest folk traditions of Karelia, the region where Finland and Russia meet.

7

Like a shaman with his horse-stick and drum, its hero Vainamoinen journeys with his

kantele

(a sort of zither) to a magic underworld inhabited by spirits of the dead. One-fifth of the

Kalevala

is composed in magic charms. Not written down until 1822, it was usually sung to tunes in the pentatonic (‘Indo-Chinese’) scale corresponding to the five strings of the

kantele,

which, like its predecessor, the five-stringed Russian

gusli,

was tuned to that scale.

8

5

Nineteenth-century philologists subscribed to the theory of a Ural-Altaic family of languages that united the Finns with the Ostiaks, the Voguls, Samoyeds and Mongols in a single culture stretching from Finland to Manchuria. The idea was advanced in the 1850s by the Finnish explorer M. A. Castren, whose journeys to the east of the Urals had uncovered many things he recognized from home.

6

Castren’s observations were borne out by later scholarship. There are shamanistic motifs, for example, in the

Kalevala,

or ‘Land of Heroes’, the Finnish national epic poem, which may suggest a historical connection to the peoples of the East, although the Finns themselves regard their poem as a Baltic Odyssey in the purest folk traditions of Karelia, the region where Finland and Russia meet.

7

Like a shaman with his horse-stick and drum, its hero Vainamoinen journeys with his

kantele

(a sort of zither) to a magic underworld inhabited by spirits of the dead. One-fifth of the

Kalevala

is composed in magic charms. Not written down until 1822, it was usually sung to tunes in the pentatonic (‘Indo-Chinese’) scale corresponding to the five strings of the

kantele,

which, like its predecessor, the five-stringed Russian

gusli,

was tuned to that scale.

8

Kandinsky’s exploration of the Komi region was not just a scientific quest. It was a personal one as well. The Kandinskys took their name from the Konda river near Tobolsk in Siberia, where they had settled in the eighteenth century. The family was descended from the Tungus tribe, who lived along the Amur river in Mongolia. Kandinsky was

proud of his Mongol looks and he liked to boast that he was a descendant of the seventeenth-century Tungus chieftain Gantimur. During the eighteenth century the Tungus had moved north-west to the Ob and Konda rivers. They intermingled with the Ostiaks and the Voguls, who traded with the Komi and with other Finnic peoples on the Urals’ western side. Kandinsky’s ancestors were among these traders, who would have intermarried with the Komi people, so it is possible that he had Komi blood as well.

9

9

Many Russian families had Mongol origins. ‘Scratch a Russian and you will find a Tatar,’ Napoleon once said. The coats of arms of Russian families - where Muslim motifs such as sabres, arrows, crescent moons and the 8-pointed star are much in evidence - bear witness to this Mongol legacy. There were four main groups of Mongol descendants. First there were those descended from the Turkic-speaking nomads who had swept in with the armies of Genghiz Khan in the thirteenth century and settled down in Russia following the break-up of the ‘Golden Horde’, the Russian name for the Mongol host with its gleaming tent encampment on the Volga river, in the fifteenth century. Among these were some of the most famous names in Russian history: writers like Karamzin, Turgenev, Bulgakov and Akhmatova; philosophers like Chaadaev, Kireevsky, Berdiaev; statesmen like Godunov, Bukharin, Tukhachevsky; and composers like Rimsky-Korsakov. * Next were the families of Turkic origin who came to Russia from the west: the Tiutchevs and Chicherins, who came from Italy; or the Rachmaninovs, who had arrived from Poland in the eighteenth century. Even the Kutuzovs were of Tatar origin

(qutuz

is the Turkic word for ‘furious’ or ‘mad’) - an irony in view of the great general Mikhail Kutuzov’s status as a hero made of purely Russian

(qutuz

is the Turkic word for ‘furious’ or ‘mad’) - an irony in view of the great general Mikhail Kutuzov’s status as a hero made of purely Russian

* The name Turgenev derives from the Mongol word for ‘swift’

(tiirgen);

Bulgakov from the Turkic word ‘to wave’

(bulgaq);

Godunov from the Mongol word

godon

(‘a stupid person’); and Korsakov from the Turkic word

qorsaq,

a type of steppeland fox. Akhmatova was born Anna Gorenko. She changed her name to Akhmatova (said to be the name of her Tatar great-grandmother) when her father said he did not want a poet in his family. Akhmatova claimed descent from Khan Akhmat, a direct descendant of Genghiz Khan and the last Tatar khan to receive tribute from the Russian princes the was assassinated in 14X1). Nadezhda Mandelstam believed that Akhmatova had invented the Tatar origins of her great-grandmother (N. Mandelstam,

Hope Abandoned

(London,1989), p. 449).

(tiirgen);

Bulgakov from the Turkic word ‘to wave’

(bulgaq);

Godunov from the Mongol word

godon

(‘a stupid person’); and Korsakov from the Turkic word

qorsaq,

a type of steppeland fox. Akhmatova was born Anna Gorenko. She changed her name to Akhmatova (said to be the name of her Tatar great-grandmother) when her father said he did not want a poet in his family. Akhmatova claimed descent from Khan Akhmat, a direct descendant of Genghiz Khan and the last Tatar khan to receive tribute from the Russian princes the was assassinated in 14X1). Nadezhda Mandelstam believed that Akhmatova had invented the Tatar origins of her great-grandmother (N. Mandelstam,

Hope Abandoned

(London,1989), p. 449).

22. (opposite)

Vastly Kandinsky: sketches of buildings in the Komi region, including a church with a Mongolian-type roof. From the Vologda

Vastly Kandinsky: sketches of buildings in the Komi region, including a church with a Mongolian-type roof. From the Vologda

Diary of 1889

stuff. Families of mixed Slav and Tatar ancestry made up a third category. Among these were some of Russia’s grandest dynasties - the Sheremetevs, Stroganovs and Rostopchins - although there were many at a lower level, too. Gogol’s family, for instance, was of mixed Polish and Ukrainian descent but it shared a common ancestry with the Turkic Gogels, who derived their surname from the Chuvash word

gogul-a

type of steppeland bird (Gogol was renowned for his bird-like features, especially his beaky nose). The final group were Russian families who changed their names to make them sound more Turkic, either because they had married into a Tatar family, or because they had bought land in the east and wanted smooth relations with the native tribes. The Russian Veliaminovs, for example, changed their name to the Turkic Aksak (from

aqsaq,

meaning ‘lame’) to facilitate their purchase of enormous tracts of steppeland from the Bashkir tribes near Orenburg: and so the greatest family of Slavophiles, the Aksakovs, was founded.

10

gogul-a

type of steppeland bird (Gogol was renowned for his bird-like features, especially his beaky nose). The final group were Russian families who changed their names to make them sound more Turkic, either because they had married into a Tatar family, or because they had bought land in the east and wanted smooth relations with the native tribes. The Russian Veliaminovs, for example, changed their name to the Turkic Aksak (from

aqsaq,

meaning ‘lame’) to facilitate their purchase of enormous tracts of steppeland from the Bashkir tribes near Orenburg: and so the greatest family of Slavophiles, the Aksakovs, was founded.

10

Adopting Turkic names became the height of fashion at the court of Moscow between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, when the Tatar influence from the Golden Horde remained very strong and many noble dynasties were established. During the eighteenth century, when Peter’s nobles were obliged to look westwards, the fashion fell into decline. But it was revived in the nineteenth century - to the point where many pure-bred Russian families invented legendary Tatar ancestors to make themselves appear more exotic. Nabokov, for example, claimed (perhaps with tongue in cheek) that his family was descended from no less a personage than Genghiz Khan himself, who ‘is said to have fathered the Nabok, a petty Tatar prince in the twelfth century who married a Russian damsel in an era of intensely artistic Russian culture’.

11

11

After Kandinsky had returned from the Komi region he gave a lecture on the findings of his trip to the Imperial Ethnographic Society in St Petersburg. The auditorium was full. The shamanistic beliefs of the Eurasian tribes held an exotic fascination for the Russian public at

23.

Masked Buriat shaman with drum, drumstick and horse-sticks. Note the iron on his robe. Early 1900s

Masked Buriat shaman with drum, drumstick and horse-sticks. Note the iron on his robe. Early 1900s

this time, when the culture of the West was widely seen as spiritually dead and intellectuals were looking towards the East for spiritual renewal. But this sudden interest in Eurasia was also at the heart of an urgent new debate about the roots of Russia’s folk culture.

In its defining myth Russia had evolved as a Christian civilization,

Its culture was a product of the combined influence of Scandinavia and Byzantium. The national epic which the Russians liked to tell about themselves was the story of a struggle by the agriculturalists of the northern forest lands against the horsemen of the Asiatic steppe -the Avars and Khazars, Polovtsians and Mongols, Kazakhs, Kalmyks and all the other bow-and-arrow tribes that had raided Russia from the earliest times. This national myth had become so fundamental to the Russians’ European self-identity that even to suggest an Asiatic influence on Russia’s culture was to invite charges of treason.

In the final decades of the nineteenth century, however, cultural attitudes shifted. As the empire spread across the Asian steppe, there was a growing movement to embrace its cultures as a part of Russia’s own. The first important sign of this cultural shift had come in the 1860s, when Stasov tried to show that much of Russia’s folk culture, its ornament and folk epics

(byliny),

had antecedents in the East. Stasov was denounced by the Slavophiles and other patriots. Yet by the end of the 1880s, when Kandinsky made his trip, there was an explosion of research into the Asiatic origins of Russia’s folk culture. Archaeologists such as D. N. Anuchin and N. I. Veselovsky had exposed the depth of the Tatar influence on the Stone Age culture of Russia. They had equally revealed, or at least suggested, the Asiatic origins of many folk beliefs among the Russian peasants of the steppe.

12

Anthropologists had found shamanic practices in Russian peasant sacred rituals.

13

Others pointed out the ritual use of totems by the Russian peasantry in Siberia.

14

The anthropologist Dmitry Zelenin maintained that the peasants’ animistic beliefs had been handed down to them from the Mongol tribes. Like the Bashkirs and the Chuvash (tribes of Finnish stock with a strong Tatar strain), the Russian peasants used a snakelike leather charm to draw a fever; and like the Komi, or the Ostiaks and the Buriats in the Far East, they were known to hang the carcass of an ermine or a fox from the portal of their house to ward away the

(byliny),

had antecedents in the East. Stasov was denounced by the Slavophiles and other patriots. Yet by the end of the 1880s, when Kandinsky made his trip, there was an explosion of research into the Asiatic origins of Russia’s folk culture. Archaeologists such as D. N. Anuchin and N. I. Veselovsky had exposed the depth of the Tatar influence on the Stone Age culture of Russia. They had equally revealed, or at least suggested, the Asiatic origins of many folk beliefs among the Russian peasants of the steppe.

12

Anthropologists had found shamanic practices in Russian peasant sacred rituals.

13

Others pointed out the ritual use of totems by the Russian peasantry in Siberia.

14

The anthropologist Dmitry Zelenin maintained that the peasants’ animistic beliefs had been handed down to them from the Mongol tribes. Like the Bashkirs and the Chuvash (tribes of Finnish stock with a strong Tatar strain), the Russian peasants used a snakelike leather charm to draw a fever; and like the Komi, or the Ostiaks and the Buriats in the Far East, they were known to hang the carcass of an ermine or a fox from the portal of their house to ward away the

’evil eye’. Russian peasants from the Petrovsk region of the Middle Volga had a custom reminiscent of the totemism practised by many Asian tribes. When a child was born they would carve a wooden

figurine of the infant and bury it together with the placenta in a coffin

underneath the family house. This, it was believed, would guarantee a long life for the child.

15

All these findings raised disturbing questions

15

All these findings raised disturbing questions

about the identity of the Russians. Were they Europeans or Asians? Were they the subjects of the Tsar or descendants of Genghiz Khan?

2

In 1237 a vast army of Mongol horsemen left their grassland bases on the Qipchaq steppe to the north of the Black Sea and raided the principalities of Kievan Rus’. The Russians were too weak and internally divided to resist, and in the course of the following three years every major Russian town, with the exception of Novgorod, had fallen to the Mongol hordes. For the next 250 years Russia was ruled, albeit indirectly, by the Mongol khans. The Mongols did not occupy the central Russian lands. They settled with their horses on the fertile steppelands of the south and collected taxes from the Russian towns, over which they exerted their domination through periodic raids of ferocious violence.

It is hard to overstress the sense of national shame which the ‘Mongol yoke’ evokes in the Russians. Unless one counts Hungary, Kievan Rus’ was the only major European power to be overtaken by the Asiatic hordes. In terms of military technology the Mongol horsemen were far superior to the forces of the Russian principalities. But rarely did they need to prove the point. Few Russian princes thought to challenge them. It was as late as 1380, when the power of the Mongols was already weakening, that the Russians waged their first real battle against them. And even after that it took another century of in-fighting between the Mongol khans - culminating in the breakaway of three separate khanates from the Golden Horde (the Crimean khanate in 1430, the khanate of Kazan in 1436, and that of Astrakhan in 1466) - before the Russian princes found the wherewithal to fight a war against each one in turn. By and large, then, the Mongol occupation was a story of the Russian princes’ own collaboration with their Asiatic overlords. This explains why, contrary to national myth, relatively few towns were destroyed by the Mongols; why Russian arts and crafts, and even major projects such as the building of churches, showed no signs of slowing down; why trade and agriculture carried on as normal; and why in the period of the Mongol occupation there

Other books

Kiss Across Time (Kiss Across Time Series) by Cooper-Posey, Tracy

Little Boy Blues by Mary Jane Maffini

Strangers on the Tube 2 by Newt, C.J.

The Grail War by Richard Monaco

Caliphate by Tom Kratman

Gently with the Innocents by Alan Hunter

Queen of Pain (Things YouCan't Tell Mama) by Pollard, D T

Wylding Hall by Elizabeth Hand

The Hunger by Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch

Trophy by Julian Jay Savarin