Natasha's Dance (76 page)

+ The theory was not dissimilar to Gordon Craig’s conception of the actor as a ‘supermarionette’, with the one important distinction that the movements of Craig’s actor were choreographed by the director, whereas Volkonsky’s actor was supposed in internalize these rhythmic impulses to the point where they became entirely uncon-scious. See further M. Yampolsky,’Kuleshov’s Experiments and the New Anthropology of the Actor’, in R. Taylor and I.Christie,

Inside the Film Factory: New Approaches to Russian and Soviet Cinema

(London, 1991), pp. 32-3.

Inside the Film Factory: New Approaches to Russian and Soviet Cinema

(London, 1991), pp. 32-3.

ancestry. In 1915 he went to Petrograd to study to become a civil engineer. It was there in 1917 that, as a 19-year-old student, he became caught up in the revolutionary crowds which were to become the subject of his history films. In the first week of July Eisenstein took part in the Bolshevik demonstrations against the Provisional Government, and he found himself in the middle of the crowd when police snipers hidden on the roofs above the Nevsky Prospekt opened fire on the demonstrators. People scattered everywhere. ‘I saw people quite unfit, even poorly built for running, in headlong flight’, he recalled.

Watches on chains were jolted out of waistcoat pockets. Cigarette cases flew out of side pockets. And canes. Canes. Canes. Panama hats… My legs carried me out of range of the machine guns. But it was not at all frightening… These days went down in history. History for which I so thirsted, which I so wanted to lay my hands on!

55

55

Eisenstein would use these images in his own cinematic re-creation of the scene in

October

(19Z8), sometimes known as

Ten Days That Shook the World.

October

(19Z8), sometimes known as

Ten Days That Shook the World.

Enthused by the Bolshevik seizure of power, Eisenstein joined the Red Army as an engineer on the northern front, near Petrograd. He was involved in the civil war against the White Army of General Yudenich which reached the city’s gates in the autumn of 1919. Eisen-stein’s own father was serving with the Whites as an engineer. Looking back on these events through his films, Eisenstein saw the Revolution as a struggle of the young against the old. His films are imbued with the spirit of a young proletariat rising up against the patriarchal discipline of the capitalist order. The bourgeois characters in all his films, from the factory bosses in his first film

Strike

(1924) to the well-groomed figure of the Premier Kerensky in

October,

bear a close resemblance to his own father. ‘Papa had 40 pairs of patent leather shoes’, Eisenstein recalled. ‘He did not acknowledge any other sort. And he had a huge collection of them “for every occasion”. He even listed them in a register, with any distinguishing feature indicated: “new”, “old”, “a scratch”. From time to time he held an inspection and roll-call.’

56

Eisenstein once wrote that the reason he came to support the Revolution ‘had little to do with the real miseries of

Strike

(1924) to the well-groomed figure of the Premier Kerensky in

October,

bear a close resemblance to his own father. ‘Papa had 40 pairs of patent leather shoes’, Eisenstein recalled. ‘He did not acknowledge any other sort. And he had a huge collection of them “for every occasion”. He even listed them in a register, with any distinguishing feature indicated: “new”, “old”, “a scratch”. From time to time he held an inspection and roll-call.’

56

Eisenstein once wrote that the reason he came to support the Revolution ‘had little to do with the real miseries of

social injustice… but directly and completely with what is surely the prototype of every social tyranny - the father’s despotism in a family’.

57

But his commitment to the Revolution was equally connected with his own artistic vision of a new society. In a chapter of his memoirs, ‘Why I Became a Director’, he locates the source of his artistic inspiration in the collective movement of the Red Army engineers building a bridge near Petrograd:

57

But his commitment to the Revolution was equally connected with his own artistic vision of a new society. In a chapter of his memoirs, ‘Why I Became a Director’, he locates the source of his artistic inspiration in the collective movement of the Red Army engineers building a bridge near Petrograd:

An ant hill of raw fresh-faced recruits moved along measured-out paths with precision and discipline and worked in harmony to build a steadily growing bridge which reached across the river. Somewhere in this ant hill I moved as well. Square pads of leather on my shoulders supporting a plank, resting edgeways. Like the parts of a clockwork contraption, the figures moved quickly, driving up to the pontoons and throwing girders and handrails festooned with cabling to one another - it was an easy and harmonious model of

perpetuum mobile,

reaching out from the bank in an ever-lengthening road to the constantly receding edge of the bridge… All this fused into a marvellous, orchestral, polyphonic experience of something being done… Hell, it was good!… No: it was not patterns from classical productions, nor recordings of outstanding performances, nor complex orchestral scores, nor elaborate evolutions of the

corps de ballet

in which I first experienced that rapture, the delight in the movement of bodies racing at different speeds and in different directions across the graph of an open expanse: it was in the play of intersecting orbits, the ever-changing dynamic form that the combination of these paths took and their collisions in momentary patterns of intricacy, before flying apart for ever. The pontoon bridge… opened my eyes for the first time to the delight of this fascination that was never to leave me.

58

perpetuum mobile,

reaching out from the bank in an ever-lengthening road to the constantly receding edge of the bridge… All this fused into a marvellous, orchestral, polyphonic experience of something being done… Hell, it was good!… No: it was not patterns from classical productions, nor recordings of outstanding performances, nor complex orchestral scores, nor elaborate evolutions of the

corps de ballet

in which I first experienced that rapture, the delight in the movement of bodies racing at different speeds and in different directions across the graph of an open expanse: it was in the play of intersecting orbits, the ever-changing dynamic form that the combination of these paths took and their collisions in momentary patterns of intricacy, before flying apart for ever. The pontoon bridge… opened my eyes for the first time to the delight of this fascination that was never to leave me.

58

Eisenstein would try to re-create this sense of poetry in the crowd scenes which dominate his films, from

Strike

to

October.

Strike

to

October.

In 1920, on his return to Moscow, Eisenstein joined Proletkult as a theatre director and became involved in the Kuleshov workshop. Both led him to the idea of

typage

- the use of untrained actors or ‘real types’ taken (sometimes literally) from the street. The technique was used by Kuleshov in

The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr West in the Land of the Bolsheviks

(1923) and, most famously, by Eisenstein himself in

The Battleship Potemkin

(1925) and

October.

Proletkult

typage

- the use of untrained actors or ‘real types’ taken (sometimes literally) from the street. The technique was used by Kuleshov in

The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr West in the Land of the Bolsheviks

(1923) and, most famously, by Eisenstein himself in

The Battleship Potemkin

(1925) and

October.

Proletkult

would exert a lasting influence on Eisenstein, particularly on his treatment of the masses in his history films. But the biggest influence on Eisenstein was the director Meyerhold, whose theatre school he joined in 1921.

Vsevolod Meyerhold was a central figure in the Russian avant-garde. Born in 1874 to a theatre-loving family in the provincial city of Penza, Meyerhold had started as an actor in the Moscow Arts Theatre. In the 1900s he began directing his own experimental productions under the influence of Symbolist ideas. He saw the theatre as a highly stylized, even abstract, form of art, not the imitation of reality, and emphasized the use of mime and gesture to communicate ideas to the audience. He developed these ideas from the traditions of the Italian

commedia dell’arte

and the Japanese kabuki theatre, which were not that different from the practices of Delsarte and Dalcroze. Meyerhold staged a number of brilliant productions in Petrograd between 1915 and 1917 and he was one of the few artistic figures to support the Bolsheviks when they nationalized the theatres in November 1917. He even joined the Party in the following year. In 1920 Meyerhold was placed in charge of the theatre department in the Commissariat of Enlightenment, the main Soviet authority in education and the arts. Under the slogan ‘October in the Theatre’ he began a revolution against the old naturalist conventions of the drama house. In 1921 he established the State School for Stage Direction to train the new directors who would take his revolutionary theatre out on to the streets. Eisenstein was one of Meyerhold’s first students. He credited Meyerhold’s plays with inspiring him to ‘abandon engineering and “give myself” to art’.

59

Through Meyerhold, Eisenstein came to the idea of the mass spectacle - to a theatre of real life that would break down the conventions and illusions of the stage. He learned to train the actor as an athlete, expressing emotions and ideas through movements and gestures; and, like Meyerhold, he brought farce and pantomime, gymnastics and circus tricks, strong visual symbols and montage to his art.

commedia dell’arte

and the Japanese kabuki theatre, which were not that different from the practices of Delsarte and Dalcroze. Meyerhold staged a number of brilliant productions in Petrograd between 1915 and 1917 and he was one of the few artistic figures to support the Bolsheviks when they nationalized the theatres in November 1917. He even joined the Party in the following year. In 1920 Meyerhold was placed in charge of the theatre department in the Commissariat of Enlightenment, the main Soviet authority in education and the arts. Under the slogan ‘October in the Theatre’ he began a revolution against the old naturalist conventions of the drama house. In 1921 he established the State School for Stage Direction to train the new directors who would take his revolutionary theatre out on to the streets. Eisenstein was one of Meyerhold’s first students. He credited Meyerhold’s plays with inspiring him to ‘abandon engineering and “give myself” to art’.

59

Through Meyerhold, Eisenstein came to the idea of the mass spectacle - to a theatre of real life that would break down the conventions and illusions of the stage. He learned to train the actor as an athlete, expressing emotions and ideas through movements and gestures; and, like Meyerhold, he brought farce and pantomime, gymnastics and circus tricks, strong visual symbols and montage to his art.

Eisenstein’s style of film montage also reveals Meyerhold’s stylized approach. In contrast to the montage of Kuleshov, which was meant to affect the emotions subliminally, Eisenstein’s efforts were explicitly didactic and expository. The juxtaposition of images was intended to engage members of the audience in a conscious way - and draw them

towards the correct ideological conclusions. In

October,

for example, Eisenstein intercuts images of a white horse falling from a bridge into the Neva river with scenes showing Cossack forces suppressing the workers’ demonstrations against the Provisional Government in July 1917. The imagery is very complex. The horse had long been a symbol of apocalypse in the Russian intellectual tradition. Before 1917 it had been used by the Symbolists to represent the Revolution, whose imminence they sensed. (Bely’s

Petersburg

is haunted by the hoofbeat sound of Mongol horses approaching from the steppe.) The white horse in particular was also, paradoxically, an emblem of the Bonapar-tist tradition. In Bolshevik propaganda the general mounted on a white horse was a standard symbol of the counter-revolution. After the suppression of the July demonstrations, the new premier of the Provisional Government, Alexander Kerensky, had ordered the arrest of the Bolshevik leaders, who had aimed to use the demonstrations to launch their own putsch. Forced into hiding, Lenin denounced Kerensky as a Bonapartist counter-revolutionary, a point reinforced in the sequence of

October

which intercuts scenes of Kerensky living like an emperor in the Winter Palace with images of Napoleon. According to Lenin, the events of July had transformed the Revolution into a civil war, a military struggle between the Reds and the Whites. He campaigned for the seizure of power by claiming that Kerensky would establish his own Bonapartist dictatorship if the Soviet did not take control. All these ideas are involved in Eisenstein’s image of the falling horse. It was meant to make the audience perceive the suppression of the July demonstrations, as Lenin had described it, as the crucial turning point of 1917.

October,

for example, Eisenstein intercuts images of a white horse falling from a bridge into the Neva river with scenes showing Cossack forces suppressing the workers’ demonstrations against the Provisional Government in July 1917. The imagery is very complex. The horse had long been a symbol of apocalypse in the Russian intellectual tradition. Before 1917 it had been used by the Symbolists to represent the Revolution, whose imminence they sensed. (Bely’s

Petersburg

is haunted by the hoofbeat sound of Mongol horses approaching from the steppe.) The white horse in particular was also, paradoxically, an emblem of the Bonapar-tist tradition. In Bolshevik propaganda the general mounted on a white horse was a standard symbol of the counter-revolution. After the suppression of the July demonstrations, the new premier of the Provisional Government, Alexander Kerensky, had ordered the arrest of the Bolshevik leaders, who had aimed to use the demonstrations to launch their own putsch. Forced into hiding, Lenin denounced Kerensky as a Bonapartist counter-revolutionary, a point reinforced in the sequence of

October

which intercuts scenes of Kerensky living like an emperor in the Winter Palace with images of Napoleon. According to Lenin, the events of July had transformed the Revolution into a civil war, a military struggle between the Reds and the Whites. He campaigned for the seizure of power by claiming that Kerensky would establish his own Bonapartist dictatorship if the Soviet did not take control. All these ideas are involved in Eisenstein’s image of the falling horse. It was meant to make the audience perceive the suppression of the July demonstrations, as Lenin had described it, as the crucial turning point of 1917.

A similarly conceptual use of montage can be found in the sequence, ironically entitled ‘For God and Country’, which dramatizes the march of the counter-revolutionary Cossack forces led by General Kornilov against Petrograd in August 1917. Eisenstein made a visual deconstruc-tion of the concept of a ‘God’ by bombarding the viewer with a chain of images (icon-axe-icon-sabre-a blessing-blood) which increasingly challenge that idea.

60

He also used montage to extend time and increase the tension - as in

The Battleship Potemkin

(1925), in the famous massacre scene on the steps of Odessa in which the action is slowed down by the intercutting of close-ups of faces in the crowd with

60

He also used montage to extend time and increase the tension - as in

The Battleship Potemkin

(1925), in the famous massacre scene on the steps of Odessa in which the action is slowed down by the intercutting of close-ups of faces in the crowd with

repeated images of the soldiers’ descent down the stairs.* The scene, by the way, was entirely fictional: there was no massacre on the Odessa steps in 1905 - although it often appears in the history books.

Nor was this the only time when history was altered by the mythic images in Eisenstein’s films. When he arrived at the Winter Palace to shoot the storming scene for

October,

he was shown the left (‘October’) staircase where the Bolshevik ascent had taken place. But it was much too small for the mass action he had in mind, so instead he shot the scene on the massive Jordan staircase used for state processions during Tsarist times. The Jordan staircase became fixed in the public mind as the October Revolution’s own triumphant route. Altogether Eisenstein’s

October

was a much bigger production than the historical reality. He called up 5,000 veterans from the civil war - far more than the few hundred sailors and Red Guards who had taken part in the palace’s assault in 1917. Many of them brought their own guns with live ammunition and fired bullets at the Sevres vases as they climbed the stairs, wounding several people and arguably causing far more casualties than in 1917. After the shooting, Eisenstein recalled being told by an elderly porter who swept up the broken china: ‘Your people were much more careful the first time they took the palace.’

61

October,

he was shown the left (‘October’) staircase where the Bolshevik ascent had taken place. But it was much too small for the mass action he had in mind, so instead he shot the scene on the massive Jordan staircase used for state processions during Tsarist times. The Jordan staircase became fixed in the public mind as the October Revolution’s own triumphant route. Altogether Eisenstein’s

October

was a much bigger production than the historical reality. He called up 5,000 veterans from the civil war - far more than the few hundred sailors and Red Guards who had taken part in the palace’s assault in 1917. Many of them brought their own guns with live ammunition and fired bullets at the Sevres vases as they climbed the stairs, wounding several people and arguably causing far more casualties than in 1917. After the shooting, Eisenstein recalled being told by an elderly porter who swept up the broken china: ‘Your people were much more careful the first time they took the palace.’

61

Meanwhile, Meyerhold was storming barricades with his own revolution in the theatre. It began with his spectacular production of Vladimir Mayakovsky’s

Mystery Bouffe

(1918; revived in 1921) - a cross between a mystery play and a street theatre comedy which dramatized the conquest of ‘the clean’ (the bourgeois) by ‘the unclean’ (the proletariat). Meyerhold removed the proscenium arch, and instead of a stage constructed a monumental platform projecting deep into the auditorium. At the climax of the spectacle he brought the audience on to the platform to mingle, as if in a city square, with the actors in their costumes, the clowns and acrobats, and to join with them in tearing up the curtain, which was painted with symbols - masks and wigs -of the old theatre.

62

The war against theatrical illusion was summed up in the prologue to the play: ‘We will show you life that’s real - but

Mystery Bouffe

(1918; revived in 1921) - a cross between a mystery play and a street theatre comedy which dramatized the conquest of ‘the clean’ (the bourgeois) by ‘the unclean’ (the proletariat). Meyerhold removed the proscenium arch, and instead of a stage constructed a monumental platform projecting deep into the auditorium. At the climax of the spectacle he brought the audience on to the platform to mingle, as if in a city square, with the actors in their costumes, the clowns and acrobats, and to join with them in tearing up the curtain, which was painted with symbols - masks and wigs -of the old theatre.

62

The war against theatrical illusion was summed up in the prologue to the play: ‘We will show you life that’s real - but

* Usually described as ‘temporal expansion through overlapping editing’. See D. Bordwell and K. Thompson,

Film Art, An Introduction,

3rd edn (New York, 1990), p. 217.

Film Art, An Introduction,

3rd edn (New York, 1990), p. 217.

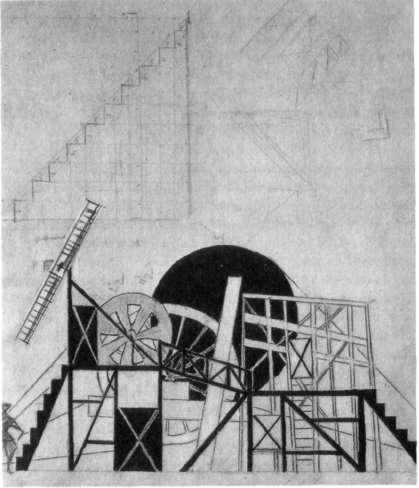

28.

Liubov Popova: stage design for Meyerhold’s 1922 production of the

Magnanimous Cuckold

Liubov Popova: stage design for Meyerhold’s 1922 production of the

Magnanimous Cuckold

in this spectacle it will become transformed into something quite extraordinary.’

63

Such ideas were far too radical for Meyerhold’s political patrons and in 1921 he was dismissed from his position in the commissariat. But he continued to put on some truly revolutionary productions. In his 1922 production of Belgian playwright Fernand Crommelynck’s

Magnanimous Cuckold

(1920) the stage (by the Con-structivist artist Liubov Popova) became a kind of ‘multi-purpose

63

Such ideas were far too radical for Meyerhold’s political patrons and in 1921 he was dismissed from his position in the commissariat. But he continued to put on some truly revolutionary productions. In his 1922 production of Belgian playwright Fernand Crommelynck’s

Magnanimous Cuckold

(1920) the stage (by the Con-structivist artist Liubov Popova) became a kind of ‘multi-purpose

Other books

Seducing Professor Coyle by Darien Cox

Crossroads by Stephen Kenson

Sidecar by Amy Lane

Compulsion by Heidi Ayarbe

His For The Night by Helen Cooper

As You Like It by William Shakespeare

On Deadly Ground (Dan & Chloe Book 2) by Flamank, Nathan L.

Midnight Sky (Dark Sky Book 2) by Amy Braun

Countdown by Unknown Author

The Outlander by Gil Adamson