Natural Order

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Fruit

COPYRIGHT

© 2011

BRIAN FRANCIS

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system without the prior written consent of the publisher—or in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, license from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency—is an infringement of the copyright law.

Doubleday Canada and colophon are registered trademarks

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES OF CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Francis, Brian, 1971–

Natural order / Brian Francis.

eISBN: 978-0-385-67154-5

I. Title.

PS8611.R35N38 2011 C813’.6 C2011-902500-0

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

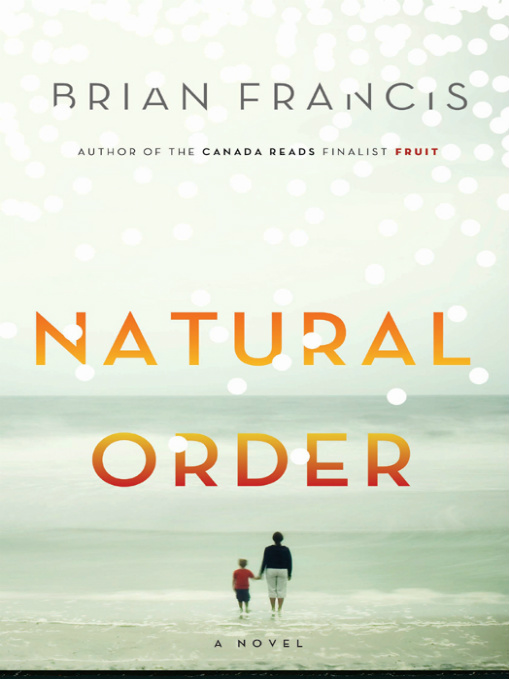

Text and cover design: CS Richardson

Cover image: © John Kuss/Corbis

Published in Canada by Doubleday Canada,

a division of Random House of Canada Limited

Visit Random House of Canada Limited’s website:

www.randomhouse.ca

v3.1

For Mom

,

my best publicist

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Acknowledgements

The Balsden Examiner

July 27, 1984

Sparks, John Charles

May 5, 1953–July 25, 1984. After a sudden illness, John passed away peacefully in Toronto in his 31st year. Survived by his loving parents Charles and Joyce Sparks of Balsden, his Aunt Helen and Uncle Richard, Aunt Irene and Uncle Dwight, cousins Marianne, Mark, Rebecca and Patricia. Friends and family will be received at the Floyd Brothers Funeral Home, 927 George Ave., on Sunday, July 29, from 7–9 p.m. The funeral service will be held at St. Paul’s United Church, 70 Ormand St., on Monday, July 30, at 12 p.m. Reception to follow. Interment to follow reception at Lakeside Cemetery. In lieu of flowers, the family requests donations to the Canadian Cancer Society.

I lived in hope. I prayed in vain

That God would make you well again

.

But God decided we must part

,

I watched you die with a broken heart

.

CHAPTER ONE

T

HE BUZZERS

keep me awake at night. That’s one thing that hasn’t gone—my hearing. Most everything else has faded. My taste. Vision. Even my voice, which comes out sounding like a scratch in the air.

The buzzers bleat in the hallway like robot sheep. We keep our strings close to us so they’re easy to reach and pull. Mine is attached to my purse. Before I go to bed, I always set my purse on my night table. During the day, when I’m in my room, I keep it on my bed. I always have it near. Sometimes, at night, when the sounds wake me, I’ll stare at my purse until I fall asleep again. It’s not a particularly nice purse. I don’t even think it’s real leather.

Most of the buzzers you hear aren’t for what you’d call real emergencies. Usually, someone needs an extra blanket. Or someone had a bad dream. More often than not, I think people pull the buzzer just to see how long it takes for someone to come to their room. I did that, the first few months after I came here. I’d pull the string and count the seconds, panic building.

17, 18, 19

What if I’d fallen out of bed? What if I was having a heart attack?

34, 35

What if I’d broken my hip?

42

What if I was dead?

Joyce Sparks

.

My name is on the wall outside my room next to a straw hat with a yellow ribbon and a couple of glued-on daisies. The hat reminds me of my sister, Helen, although it isn’t hers. The social coordinator had us make our own hats for a tea party last spring. I don’t know why someone decided to hang my hat outside the door. I didn’t do a nice job of it. I’ve never been good at crafts. I don’t have the patience.

Ruth Schueller

is the name on the other side of the door. She’s my roommate. She doesn’t have a hat next to her name because she wasn’t at the home in the spring. Instead, there’s a black-and-white photograph beside Ruth’s name, taken during her younger years. I hardly recognize her. Frightening how much damage time does to a face. Ruth is eighty-two. I turned eighty-six in July.

Ruth snores something awful. Not at night, usually. But during her daytime naps, she makes the most horrific sounds. She’ll fall asleep in her wheelchair and her head will flop down like a dead weight. That’s when the snoring starts. Some days, it’s so loud I can’t concentrate on the television, even when the volume is turned up all the way—which it usually is. I’ll have to throw the Yellow Pages at her. (Never at her head, although I’ve been tempted. Only at her feet.) Then I’ll watch her out of the corner of my eye as she tries to sort things out. What was that noise? Where did this Yellow Pages come from?

Last week, I wheeled into the bathroom and found my hairbrush on the back of the toilet tank. This bothered me because I always keep my brush next to the faucet. I wheeled out of the bathroom, carrying my brush like a miniature sword.

“RUTH, DID YOU TOUCH THIS?”

She blinked back at me like I was talking another language.

“IT’S NOT RIGHT!” I said. “YOU CAN’T DO THINGS LIKE THAT!”

I don’t know why they can’t give me a roommate who can talk. Ruth is the second mute person I’ve had in the past year. She replaced Margaret, who was also soft in the head. She’d sit in her chair, knuckle deep inside a nostril for most of the day.

“If you find an escape route up there, let me know,” I’d say to her. Then Margaret’s liver shut down and she turned bronze. She lay in her bed, day after day, while a string of family members I’d never seen before came in and out of our room. They stood at her bedside, joisted fingers over their bellies, looking down at Margaret and shaking their heads as though this was one of the greatest tragedies they’d ever witnessed.

It’s not nice having someone die in your room. I’ll say that much. I woke up in the middle of the night, the sheep bleating in the distance, and even though I couldn’t see her, I knew Margaret was gone. There was a stillness in the air, a cold pocket. I thought about reaching for my purse, but then wondered if it mattered. I didn’t want to deal with the commotion that would follow: the lights turning on, whispers, white sheets. So I lay there with my hands at my sides and said a short prayer for Margaret. Although she couldn’t talk, I could tell by her eyes that she’d been a good person. Kind. Gentle. She hadn’t deserved her fate. After a while, I fell back asleep.

One week later, Ruth moved in. She’d been living on the second floor where the other soft-headed people are, but her family wanted her on my floor, the fourth. Did they think she’d be more stimulated up here?

I suppose it could be worse. There’s Mae MacKenzie down the hall, trapped with that horrible Dorothy Dawson. Dorothy keeps the divider curtains shut so the room is cut in half. She even safety-pinned the flaps together. She means business.

“She trapped herself in once,” Mae told me. “Kept pawing her way around, trying to find the opening. It was the best entertainment I’ve had here yet.”

Dorothy doesn’t talk to anyone. Mae says she’s a bitter woman. There’s been some talk of a husband who had wandering hands. A daughter into drugs.

“Some people get a rough ride in life,” Mae said with a slow shake of her head.

I held my tongue.

The room that Ruth and I share is small, but big enough for two beds, two dressers and two wheelchairs, which I suppose is all the space that a couple of old ladies need. We’re on the south side of the building, so we don’t have the nice view of the lake. Instead, we face the street. I guess I can’t afford the lakeside setting. I’m guessing because I don’t know for certain. My niece, Marianne, handles my finances. She lives in Brampton. I call her once a month or so, but we don’t talk for more than five minutes. It always seems like someone is pulling on her arm. The last time I saw her was January. She showed up in my doorway wearing a dark brown blouse. She’d put on weight.

“Happy belated New Year, Aunt Joyce,” she said and sat down on the edge of my bed.

She looked like a bonbon left out on a hot day.

I shouldn’t be critical. That was Helen’s problem—always after Marianne and her son, Mark, to live up to some idea of perfection. Now look at them. Marianne is fat and divorced and Mark had a heart bypass two years ago. But I was grateful for Marianne’s company that day. I don’t have visitors, and living here makes you feel removed from the simplest things. I don’t remember the last time I went grocery shopping. Or to Sears. Or ate in a restaurant. Or visited the cemetery.

Sometimes, when I look around my room, I think, “This is the last place I’ll live.” When I go, they’ll be able to pack all my belongings in a cardboard box. I like to think I’m simplifying my life. Maybe it’s the other way around.

I’ve been here at Chestnut Park for six years. Marianne pressured me into it. I’d fallen in the bedroom in my senior’s apartment. I couldn’t be trusted on my own anymore.

“You’ve always taken care of others, Aunt Joyce,” she said to me. “Now it’s time to let people take care of you.”

I hadn’t taken care of anyone in my life. If anything, the opposite was true. But I was too tired and frightened to argue. My arm was stained with bruises and my ankle was swollen like a cantaloupe. I’d lain there, sprawled out between the bed and my dresser, for what seemed a lifetime. (They figured it was close to a day before the superintendent let himself in. Imagine my relief—and my shame when he found me on the floor, my legs wide open.)