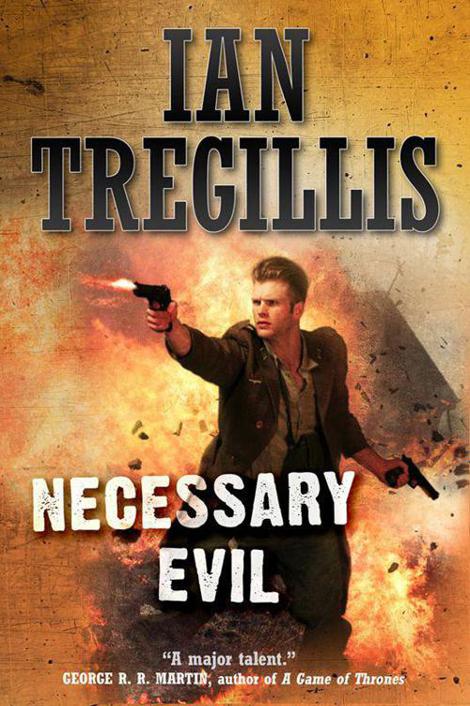

Necessary Evil (Milkweed Triptych)

Read Necessary Evil (Milkweed Triptych) Online

Authors: Ian Tregillis

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

For Kay, the classiest lady I know

Acknowledgments

Once again, I am indebted to my friends, colleagues, and mentors in Critical Mass, who helped me shepherd this story from a rough idea to a finished trilogy. This year it was Terry England, Ty Franck, Emily Mah, Vic Milán, John Miller, Melinda M. Snodgrass, S. M. Stirling, and Walter Jon Williams who braved the first drafts. Thanks to everybody who stuck with me on this project.

Thanks also to S. C. Butler and Char Peery, Ph.D., for critical reading; Michael Prevett for smart questions; Edwin Chapman for copyediting; and Kay McCauley for her faith in me.

Finally, heartfelt thanks to my editor, Claire Eddy.

Contents

This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more.

—Friedrich Nietzsche

Oh God! Oh God! That it were possible / To undo things done; to call back yesterday.

—Thomas Heywood

prologue

She is five years old when the poor farmer sells her to the mad doctor.

It is autumn, damp and cold. Hunger twists her stomach into a knot. She kneels in a smear of oak leaves, holding a terrier by the hind legs while her brother tries to wrestle the soup bone from its mouth. The bone is a treasure, glistening with flecks of precious marrow. The dog growls and whimpers; they do not hear the wagon approach.

The farmer asks if they are hungry. He says he knows somebody who can feed them, if they’re willing to take a ride in his cart.

They are. The dog keeps the bone.

She huddles in the hay of the farmer’s wagon. Brother holds her, tries to fend off the seeping cold. Another boy rides with them. His chest gurgles when he coughs.

They arrive at a farm. The field behind the house is studded with little mounds of black earth. Here and there, ravens pick at the mounds. They pull at tattered cloth, tug on scraps of skin.

A doctor inspects the children. She realizes he will feed them if he likes what he sees. But he hates weakness.

She watches the coughing boy. Illness has made him weak. And she is so very hungry.

She trips him. The doctor sees his weakness and it disgusts him. Soon there is another mound behind the farmhouse. And there is more food for her.

She considers doing the same to the boy called brother. Perhaps she could know the comfort of a full belly. But brother wants to help her. And she might want other things after the hunger has passed.

Brother lives.

*

It is winter, long and dark.

The doctor is a sick man, driven to madness by the weight of his genius. And he is looking for something. He purchases children in order to remake them. He hurts them, cuts them, in his desperate search for something greater.

The days are full of scalpels, needles, shackles, drills, wires. The stench of hot bone dust, the metallic tang of blood, the sting of ozone. The nights are full of whimpering, crying, moaning. Torments pile up like snowflakes. So do the bodies behind the farmhouse.

Brother tries to protect her. He is punished.

But she survives. Sometimes the pain is pleasant; when it isn’t, she retreats to the dark place in her mind.

Brother survives, too. She is glad. He is useful.

The doctor operates on her, over and over again. But no matter how many times he opens her skull, no matter how often he studies her brain to awaken a dormant potential that only he believes is real, he never notices that she is different. He does not see that she is like him.

In the meantime, she discovers the joy of poetry. The pleasure of arranging dried wildflowers. She collects sunrises and sunsets.

She grows. So does brother. Taller. Stronger. Wiser. And they are joined by others—a rare few who endure years of the doctor’s scrutiny. She and brother differ from the others. Their skin is darker, like tea-stained cotton, and their eyes like shadows, while the others have light skin and colorful eyes. But she and brother survive, and so the doctor keeps them.

One day, deep in that long winter, the doctor sees his first success. His tinkering unleashes that elusive thing he calls the Will to Power. But it consumes the boy upon whom he is working. The screams shatter windows and crumble bricks in those few moments between transcendence and death.

The doctor, vindicated by this fleeting triumph, redoubles his efforts. He drills wires through their skulls, embeds electrodes in their minds. Electricity, he decides, is key to unleashing the Will to Power. When it does not work he opens their skulls and tries again. And again. The doctor is a patient man.

Sometimes the pain is so great that the oubliette in her mind is scarcely deep enough to keep her safe. Some of the others break; they become imbeciles, or mutes. Those who do not break are warped. The doctor is their father; they strive to please him. They think they can. But she knows better. They don’t understand the doctor as she does.

The doctor connects their altered minds to batteries. And, one by one, the survivors become more than human. They fly. They burn. They move things with their minds.

Yet she is a puzzle the doctor cannot crack. He takes her into the laboratory again and again. But nothing works. She is unchanged by the surgeries. Until one morning.

When she wakes, her mind is ablaze.

She is wracked by apparitions. Assaulted with visions of unknown places and people. Brilliant, luminous, the images streak through her mind like falling stars flaring across the heavenly vault of her consciousness. The heat of their passage rakes her body with fever.

The light show etches patterns inside her eyelids. A shifting, rippling cobweb of fire and shadow enfolds her mind. It hurts. She flails. Tries to tear free of the web. But she cannot separate herself from the luminous tapestry any more than the sea can divest itself of wet. It is a part of her.

She fumbles for something constant. Through sheer willpower she forces her mind to focus, to pluck a single image from the chaos before the cascade drives her mad.

Everything changes.

The web shimmers, ripples, reconfigures itself. A new sequence of visions assaults her senses. She sees them, feels them, smells and tastes and hears them.

The earth, swallowing brother.

The doctor, wearing a military uniform.

War.

Oblivion, vast and cold and deeper than the dark place in her own mind.

She passes out.

When next she wakes, she is sprawled on the stone floor of her cell. Brother kneels over her. He cradles the back of her head, strong fingers running through the stubble of her shaven skull. His fingertips come back glistening red. His eyes widen. Brother tells her not to move, takes the pillow from her cot, slides it beneath her head.

Trembling and cold, she watches it all through the shimmering curtain, past pulsing strands of silver, gold, and shadow. The images wash over her again.

Brother standing … rushing into the corridor … bowling over one of the others in his haste to summon the doctor … angry words … the corridor erupting in flames … she is trapped her skin bubbling blackening shriveling in the inferno heat twisting her body ripping the breath from her lungs before she can scream the agony oh god the agony she is burningtodeathohgodOHGOD—

Brother runs for the door.

She is going to dieohgodtheagonyohgod—

She cries out. He pauses in the doorway.

The shimmering cobwebs flicker, blink, reconfigure themselves again.

The future changes. There is no fire.

*

It is springtime, bright and colorful.

Her Will to Power has manifested, and it is glorious.

The cascade of experiences still assaults her like a rushing cataract, still threatens to sweep her away to permanent madness. A lesser person would embrace insanity for succor and refuge. But not her. She understands now.

The scenes she experiences are snippets of her own future. One of her possible futures. One of an infinity.

The Götterelektron flows up her wires, enters her mind, hits the loom of her Willenskräfte and explodes into a trillion gossamer threads of possibility. A tapestry of potential time lines fans out before her. Countless golden strands, each future path branching into uncountable variations, and innumerable variations on those variations, on and on and on and on. Each choice she makes nudges the world from one set of paths to another.

She is a prophet, an oracle, a seer. She is nothing less than a vessel of Fate.

The web of possible futures is infinitely wide and grows wider the further she looks. It takes strength of mind and will to plumb the depths, to explore the far fringes of possibility. There is a horizon that limits her omniscience, a boundary built from her own weakness.

In the first fragile hours of her new ability, she can’t peer ahead any further than a few moments. Brother runs for the doctor, she dies in fire; he stays, she lives.

With practice, she pushes the horizon back several hours. Tell brother she is hungry: he comes back with stew, bread, and cherry strudel. Wait an hour, then tell him: there is no strudel left. Wait two hours, then tell him she is ravenous: the doctor catches him breaking curfew, punishes him with a night and a day in the coffin box; brother rips off his fingernails trying to claw out.

With several days’ practice, she can follow the time lines almost a week into the future. Steal a knife from the kitchen, stab brother in the neck: whole branches of the infinite web disappear and are replaced with others that begin with a shallow grave and a sack of quicklime.

The process is beautiful. Mesmerizing. She watches it again and again.

She learns to focus her will like a scalpel, learns to prune the decision tree, learns to slice away the gossamer tangle of unwanted possibilities.

The further she pushes the horizon, the more powerful she becomes. Yet there are still things she cannot do, events she cannot bring to fruition. She cannot make it snow in June. She cannot make brother fall in love in the next two days. Nothing she does will cause the doctor to tumble down the farmhouse stairs and break his neck in the next six hours. But push the horizon back, and possibilities open up. Why hurry? In three days’ time the skies will open with a torrential downpour. The doctor will wear galoshes. He will leave them outside his door on the third floor of the farmhouse lest he track mud inside. He oversees the daily training exercises from his parlor window. She distracts one of the others with a well-timed wink; he loses his concentration and destroys delicate equipment in an explosion of Willenskräfte. The doctor flies into a rage. Throws the door open. Does not see the galoshes. Lands at the bottom of the stairs with splinters of vertebrae poking through his lifeless neck.